Thomson, Basil Home

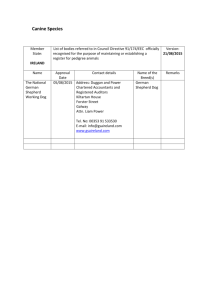

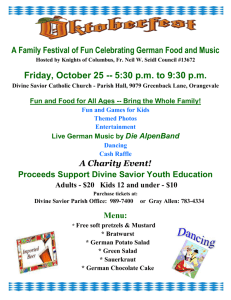

advertisement