BIODIVERSITY HOSPITAL

advertisement

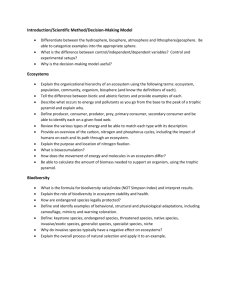

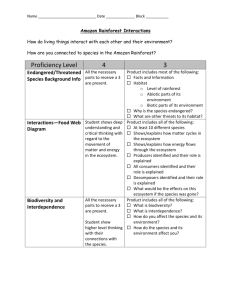

Temperate Rainforest in the Pacific Northwest Teachers’ Notes Who is it for? 7-11 year olds How long will it take? This activity should take a minimum of five to six one-hour classroom sessions. These sessions can be taught sequentially or as an independent project over the course of a term with the final presentation being a performance assessment. Learning outcomes: Students investigate ecosystems and understand that they include living and non-living things. They develop basic food chains identifying producers and consumers. They become aware that plants and animals depend on each other and on the non-living resources in their ecosystem to survive. They understand that ecosystems can change through both natural causes and human activities, and that humans can help to protect the health of ecosystems in a number of ways. What do you need? Access to a plot of land with an unsealed surface (ideally a forest area, grassland or a park but if that’s not possible, a section of the school grounds with some trees or bushes will suffice) Tape measure Rope or string Magnifying glasses Small sealable plastic bags Note paper and pens Living and Non-Living Things worksheet Temperate rainforest of the Pacific Northwest classroom presentation (PowerPoint) Taxonomy books and local field guides to identify organisms (optional) LCD projector Access to the Internet Summary: The following series of activities will introduce students to the temperate rainforest in the Pacific Northwest (USA). Students will conduct a hands-on investigation of a small local ecosystem, catalogue their findings, and then compare their findings to that of the temperate rainforest. The comparison will provide students with an appreciation for the uniqueness and biodiversity of the temperate rainforest and they will begin to understand that this ecosystem is the home for a range of endangered species whose survival will depend on keeping this habitat intact. In the final session(s), students will document their new understanding and become advocates for protecting ‘hotspot habitats’ and demonstrate how everybody can contribute to their survival. 1 Session1: Students explore a local plot of land, take note of all the organisms that they find, and group them into living and non-living things. Session 2: Students explore the concept of food chains and create a simple food web for some selected species that they have found in the plot of land they explored the previous day. In the second part of the session, students get introduced to the temperate rainforest in the Pacific NW. Provided information will allow them to do a comparison with their local habitat. Session 3: Students deepen their knowledge about the Pacific NW. Students will look at some specific threats to the ecosystem to develop the idea that a change in an ecosystem (for instance an increase in logging or invasive species) can have a severe impact on the entire ecosystem and its species. They also learn that a range of species, including some rare and threatened ones (e.g. spotted owl, bald eagle, brown bear and black bear, olympic marmot, marbled murrelet, Washington ground squirrel, Mohave ground squirrel, wolf) depend on the temperate rainforest for survival. Session 4: In small groups, students choose an (endangered) species found in the Pacific NW and deepen their understanding of what this species needs to survive and what kinds of threats it faces. Students then brainstorm the future of the Pacific NW if the major threats to the ecosystem cannot be stopped and think about how they can document and present all this information to others. Session 5: Students present their poster to invited guests. Session 6: Students discuss the kinds of threats their chosen species are faced with and think about what they can do to help. Each group compliments their presentation on the rainforest and its selected endangered species by a ‘call for action’ in which they outline ideas for how everyone can contribute to ensure that the temperate rainforest in the Pacific NW will be protected for future generations. Preparation guidelines: 1. Read through the notes and review the Pacific Northwest classroom presentation. 2. Identify an area of land that is unpaved, easily accessible, and safe for students to explore. Preferably, the land should be in its natural state with as little human intervention as possible (such as a section of land along a river, lake, a forest, or park; if nothing else is available, then a section of the school campus). Familiarize yourself with this habitat and the species that can be observed there. Identify the safest way for you to take your students there in Session 1. 3. Review the living and non-living worksheet and make copies for Session 1. 4. Obtain identification books for local species (optional). 5. Arrange for a computer and projector to show the Pacific Northwest classroom presentation in Session 2. 6. If possible, arrange for Internet access (and computers and printers if available) for Sessions 3 and 4, so students can supplement their research with online information from www.arkive.org. 7. For Sessions 4-6, students can create and present their final presentations electronically (for instance on PowerPoint) or on large paper. Make sure the appropriate materials and space are available. 2 How to run the sessions: Session 1 1. Begin the first session by taking the students outside to the piece of land that you identified. 2. Introduce students to the land and its boundaries (for safety reasons you might want to limit it so all sections are visible to you at all times) and share with them that in today’s session, they will have the opportunity to explore a section of this land. Let them know that each group will be allowed to choose their own plot where they hope to find as many different things to document as possible (living and non-living). 3. Divide your students in groups of 3-4 students and provide each group with a rope (suggested length between 4 and 10 meters) and pegs to mark the boundaries of their selected section. In addition, provide them with a magnifying glass for closer observations, zip lock bags 1 if they want to collect some examples to share later, and pen and paper for note-taking. 4. Tell students how much time they have to complete the task and tell them to choose their land and mark its boundaries with the rope and pegs. Then they can begin exploring and taking an inventory of their plot. 5. Once students have identified their plot, start circulating amongst them and ask questions such as: Why did you choose this section? What do you expect to find here? The point of these questions is simply to identify students’ thinking about where they expect the most findings and what they hope to find. Accept all rational answers except if students chose totally randomly. If that’s the case, remind them that their task was to find a spot where they expect to make as many different findings as possible. At this point, it is not yet important to discuss the variety of species, etc. that can be found. Keep reminding students to look for as many different things as they can find (large and small) and to document it all. To help them with their documentation, hand out the worksheet Living and Non-Living Things (one per group is sufficient). If students ask for help identifying certain objects, it would be good if you had a local guide book, otherwise tell them that a close description or sample will do for now and that they can try to identify it later. 6. Make sure that half-way through this session, each group has been handed the worksheet Living and Non-Living Things and that all groups are on task. Keep circulating and push their observations so they consider all aspects of living and non-living things that can be found. Try not to tell them what to look for but to guide their observations with questions and prompts. For instance, if they say they have covered everything, check whether they have also looked at the very small objects that can be found on grass, in the soil, on bark, etc. Hand them the magnifying glass and ask them whether they can find a ‘hidden world’ with more things that they have not listed yet. Also listen to their conversations about what is living and non-living and how they decide which is which. It is okay if they do not have a specific definition yet in mind but use their reasoning to justify their recordings. If groups make good progress with those tasks, you can also add the question to ‘quantify’ their findings: Of which ‘objects’ do you have the most in your plot of land? 7. Five minutes before you have to head back, give students a time warning, so they are prepared to wrap up their observations and recording. 1 Supervise and advise students in what they can collect and what they should leave untouched and just sketch in a notebook. You could also bring a terrarium, etc. to keep live animals for better study in the classroom so they can later be released unharmed. 3 8. Collect the materials you handed out and tell students to hold on to their notes, samples, and worksheet and make sure that they have it with them for the next session. (You may wish to collect and keep it in the classroom rather than students taking it home). Session 2 – Part A 1. Before returning to last session’s exploration, ask students what humans need to survive. Record their responses on the board. Make sure it covers the most essential (food and water, air to breathe and clothing/shelter as protection against the environment). Point out that humans need living and non-living things to survive. Then challenge students to pick food items that they consume and think about where they come from. By tracing the food item back to its beginning, try to establish a basic food chain. Establish the terms producer and consumer and remind students that all living things require a minimum of food (energy), water and air to survive. 2. Return to the previous session and ask students to report back on their findings. What living and non-living things did they find in their plot of land? Based on their examples, try to discuss characteristics that distinguish living from non-living things. Examples can include: it requires food, water and air, it grows, can reproduce, it dies, it can move, etc. It is more important for students to reason with one another about the criteria rather than developing a complete list. Have students discuss any ‘things’ that they couldn’t place into living and non-living from their exploration and decide as a class whether it is a living or a non-living thing based on their established criteria. 3. Send students back into their groups from the last session. Tell them to take the three most common living things in their plot and develop a food chain for each one of them. Tell students to first focus on all the things that they observed but then use their imagination and prior knowledge to envision how the food chain could be extended. You may extend this discussion by asking students why they think there are usually more producers than consumers in a habitat. 4. Optional: Discuss the food chains and try to consolidate them in a giant food web depicting the interdependence of all living things in the plot of land they studied. 5. Discuss what could happen if a change occurred that would, for instance, eliminate a species from the food chain (web) caused by a disease. Students’ responses should vary but it is important that they realise that any event that affects one organism in an ecosystem may indirectly affect all others and that a seemingly small change could potentially have far reaching consequences. You may also wish to discuss that often we can’t predict what kind of changes will happen to a system when a change occurs since nature is very complex. Session 2 – Part B 1. Introduce students to the ecosystem of the Pacific Northwest. As an overview, you may choose to show the provided PowerPoint Temperate Rainforest of the Pacific Northwest (slides 1-6), that depict some background information as well as common, endemic, and endangered species found in that area. 2. Compare and contrast the Pacific Northwest to the ecosystems in your local area. Include location, size, average temperature/rainfall (and annual distribution), as well as the biodiversity found in each with sample species that are common, endemic, and endangered. Students should realise that the ecosystem of the Pacific Northwest is quite unique and is the home of many endemic and endangered species. 3. Have students form groups based on interest and have each group choose two of the endemic or endangered species of the Pacific Northwest that they would like to research further. Encourage students to choose at least one plant or an aquatic species. For more guidance, refer to the document ‘Selected Resources’. 4. In the following session, students will work in their groups to address the following main questions: a) What does the species need to survive and where is it in the food chain (or food web)? 4 b) Is the population steady or decreasing? If decreasing, what are the threats that primarily cause the decrease in numbers? Session 3 – Part A 1. Allow the first half of this session for students to research background information on their chosen species. If possible, provide them with access to the Internet and point them to www.arkive.org to begin with. Remind them that they need to find answers to the following questions: a) What does the species need to survive? b) Where is it in the food chain (or food web)? c) Is the population steady or decreasing? If decreasing, what are the threats that primarily cause the decrease in numbers? 2. Instruct them that in their group they need to prepare a brief of their two species to share with the others. The brief could be prepared electronically or on paper. Session 3 – Part B 1. In the second half of this session, bring the class together to discuss the threats that they have identified for their species. Begin a list of threats on the board. Then focus on unsustainable forestry practices and human development, since those are major threats not just in the Pacific Northwest but also in many other ecosystems worldwide. [Note: climate change is another globally applicable threat. However, addressing this threat in greater depth is beyond the scope of this activity but would make a great extension if time is available.] 2. You may wish to use the PowerPoint Temperate Rainforest of the Pacific Northwest (slides 79) to give students an overview of the situation. 3. Discuss with students potential consequences to the ecosystem and the food chains (or webs) if those threats continue. Session 4 1. Students use this session to complete their research and prepare a presentation or poster that showcases the students’ chosen species in their habitat and discusses any potential threats they face. Session 5 1. Students present their posters. When students listen to the other groups’ presentations, ask them to pay close attention to the threats the presented species face and the possible consequences to the food chain/web. Inform them that the whole class will try to compile a list of threats to the species in the Pacific Northwest and the potential consequences of these threats for the entire ecosystem. 2. Create a summary concept map with the entire class covering the endemic or endangered species of the temperate rainforest of the Pacific Northwest, the threats that they face, and potential consequences for the future of that ecosystem. 3. Use the final minutes of this session to ask students to brainstorm solutions for the problems and how the threats could be stopped. Include in this discussion what can be done locally? Nationally? What can each student contribute themselves? Accept any ideas at this point. Session 6 1. Wrap up this entire unit by using this final session for a ‘call for action’. Although the temperate rainforest of the Pacific NW is, for most students, far away and they might never visit it, they should be aware that even local choices and deeds can have far reaching consequences. By discussing conservation efforts that they themselves can implement in 5 their own lives, they can contribute to maintaining ecosystems locally, nationally and globally. You can start the conversation by returning to the problem of unsustainable logging practices and discuss that students can make better choices by avoiding woods/furniture that stem from original forests, recycle paper, or better – use less of it in the first place. 2. Spend the last 15 minutes developing a ‘class commitment paper’ on which the students agree on the kind of changes they want to implement so they can contribute to conservation efforts. Note, if you have any such efforts happening in the community, you might want to support those in addition to the efforts the class decide to endorse. 3. Hang up the ‘class commitment paper’ in the classroom so it can guide students in changing their behavior as they try to contribute to conservation efforts. Going Deeper - Additional Online Resources from ARKive: What is an Endangered Species? - This activity (for 7-11 year olds) challenges students to think about what it means to be an endangered species and what causes a species to become endangered. Climate Change – A series of resources that address the causes and consequences of climate change in regards to ecosystems and endangered species, as well as suggestions for how individuals can get involved to help reduce the effects of climate change. Extension activities: Have students expand their exploration by choosing a larger local ecosystem that they can study for several months or even a year. Students can systematically catalogue all the living and non-living things that make up that habitat and support their findings with photographs. In a final documentation (letter to the newspaper, local exhibit, etc.) students should list the different species that they found, report what they learned about them, the problems that they encountered, and any new insight they gained identifying the sustainability of that ecosystem and its biodiversity. Threats to the genetic diversity of endangered species (an extension for older or more interested students): Declining populations can grow again when they are protected in the wild. There are also methods available to breed endangered species in captivity. However, the loss of genetic diversity presents a serious threat that is hard to overcome. Have students look into the methods that are being tried by conservationists and zoos to breed endangered species. Research the effects of climate change on selected ecosystems and the species found there. 6