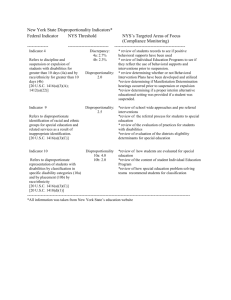

Disproportionality in Child Protective Services: The

advertisement