1 February 17, 2006 Jefferson County Land Development c/o Philip

advertisement

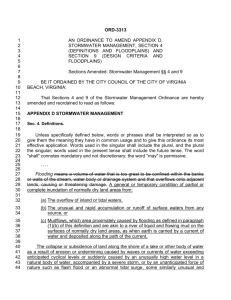

Nelson Brooke Black Warrior RIVERKEEPER 712 37th Street South Birmingham, AL 35222 Phone: (205) 458-0095 Fax: (205) 458-0094 nbrooke@blackwarriorriver.org www.blackwarriorriver.org February 17, 2006 Jefferson County Land Development c/o Philip Richardson 716 Richard Arrington Jr. Blvd. N. Room 260, Courthouse Birmingham, AL 35203 Via e-mail: richardsonp@jccal.org Re: Jefferson County Higher Regulatory Standards Floodplain Management Ordinance Dear Mr. Richardson: Floodplain ordinances are created to control development in order to minimize the disturbance of a floodplain’s floodwater carrying capacity. Floodplains operate best when left alone, in their natural state. However, this has not been the case in Jefferson County over the years – floodplains have been altered by stream channelization, logging, mining, the filling of wetlands, and leveling of landscapes for development. Developments have paved over a large percentage of this place we call home. According to the Jefferson County Stormwater Management Authority’s (SWMA) Jefferson County Urban Canopy Study from the summer of 2001 through the summer of 2003: the city of Birmingham is 48% developed. The result of this amount of development is a drastic reduction in the landscape’s ability to absorb water. The first stage of development is the loss of trees and vegetation. According to SWMA’s study, a single full-grown tree will use 760 gallons of rainwater per year. The economic value of trees with regard to stormwater management cannot be disputed. Once vegetative cover is gone, the soil is exposed and vulnerable to runoff. Initially, poor best management practices during construction inadequately retain sediment during rain events, washing away topsoil and filling in drainages and streams, causing a reduced carrying capacity for floodwaters. Once this capacity is lost, the water must move outside of its normal floodplain causing flooding beyond that which was previously seen – with elevated severity and range. With development comes a large amount of impervious surfaces that cannot absorb rainfall – such as roads, parking lots, and roofs. Without a way to absorb, slow down, and retain runoff, impervious surfaces contribute to a drastic increase in runoff velocity. As a result, flash floods and stream bank scouring ultimately contribute more sediment to an already taxed streambed. This is a vicious cycle that only gets worse without significant changes in the way we develop. Preserving green space within developments- especially along streams, the use of pervious materials for pathways and parking areas, the use of green roofs, and innovative stormwater engineering techniques can effectively reduce the net runoff and runoff velocity from a given development. 2 Jefferson County now has a flood mitigation program which is working to educate home buyers about the presence of floodplains, a buyout program for people living in homes devastated by flooding, and a land trust orchestrating the establishment of greenways for the vital protection of stream buffers in the floodplain. We must not allow an ordinance that would threaten this vital program. The original Jefferson County Higher Regulatory Standards Floodplain Ordinances from November 8, 2004, and subsequently April 28, 2005 – both created by county staff - were a step in the right direction. These were somehow replaced by the newer Floodplain Management Ordinance from November 4, 2005, which has some serious omissions: ● The cumulative impacts of development within the floodplain are not considered. We must adequately address the result of fill within the floodplain, and take into account developments upstream of and outside of the floodplain that are negatively affecting hydrology. Having engineers submit “no-rise certifications” on a project-by-project basis will not get the job done. ● Regarding fill within the floodplain, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers must be consulted due to Section 404 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972. Although this is not the county’s jurisdiction, it is prudent to let developers know of this important step. ● This ordinance implies that fill within the floodplain will not detrimentally contribute to increased flood levels, yet anyone with common sense knows that this is not true. Under ARTICLE 4. PROVISIONS FOR FLOOD HAZARD REDUCTION, SECTION 400. GENERAL STANDARDS, A., 13. Floodway Encroachments, a., this ordinance reads: “Encroachments within the Regulatory Floodway, including earthen Fill, New Construction, Substantial Improvements or other Development are permitted, provided it is demonstrated through hydrologic and hydraulic analyses performed in accordance with standard engineering practice that the Encroachment shall not result in any increase in flood levels or Floodway widths during a Base Flood discharge.” According to ARTICLE 6., DEFINITIONS: “ ‘Base Flood’ means the Flood having a one percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year.” This is allowing fill within the floodplain that will not impede floodwaters comparable to a one-year flood event. It WILL impede a large flood event such as a 25-year, 50-year, and 100-year event. Under ARTICLE 4., SECTION 400., A., 13., c., this ordinance reads: “Encroachments within the Floodway Fringe Area are permitted.” According to ARTICLE 6., DEFINITIONS: “ ‘Floodway Fringe Area’ means the portion of the Special Flood Hazard Area outside the Floodway. The area between the Floodway and the boundary of the 100-year flood is termed the Floodway Fringe. The Floodway Fringe thus encompasses the portion of the Floodplain that could be completely obstructed without increasing the water surface elevation of the 100-year flood more than 1.0 feet at any point.” Fill within this area will aim to protect new developments from the 100-year flood, while causing an increase in the range of a 100-year flood. Property outside of current flood range will then become susceptible to flooding. Allowing unconditional fill within the “Floodway Fringe Area” will pass the burden of flooding on to those who live downstream. This is no way to manage a floodplain. ● Stormwater engineering practices effective in slowing down and absorbing runoff from developments need to be encouraged, or even better – required. New, innovative designs for the control of stormwater leaving sites can positively affect the cumulative impacts of development. Current stormwater engineering designs do little to slow down and manage runoff. Some developments are using retention ponds, but usually only when required to do so. In order to affect the net runoff issues we are currently facing, everyone must pitch in to reduce their impact. 3 ● Compensatory storage is absent from this ordinance. When fill is placed in the floodplain, compensatory storage must be required in order to offset the disturbance. ● Mitigation and restoration are not mentioned. We must be held accountable for our actions, especially when they can cause harm to people downstream. Wetlands mitigation and stream bank restoration are vital to protecting the integrity of floodplains within Jefferson County. Wetlands are vitally important: helping to absorb rainwater and replenish aquifers during floods. Natural stream channels meander like a snake, and this is for a reason. These sharp bends help to slow water down and create a series of pools and riffles. Channelization of streams causes an increase in water velocity and contributes to stream bank scour and flash flooding. Mitigation and restoration are rare in Alabama, as is the recognition of their importance. We must begin to heal the damage that was done in the past in order to alleviate the problems we are facing now. This is an opportunity for jobs, for the diversification of our economy as we see it. ● Water quality, recreation, wildlife, and endangered species are left out of this equation. Some have said that this is not an environmental document. No, it is not. However, it must be understood that everything in this natural system is connected. To not consider the implications of this ordinance on our natural environment, on our quality of life, is to not understand the big picture. Unchecked development will contribute to increased flooding, which causes damage to public infrastructure and private property. The resulting pollution will threaten our sources of fresh water for drinking, cooking, bathing, and washing. Pollution will also be detrimental to our recreation opportunities and the survival of wildlife. A strong floodplain ordinance can go a long way towards minimizing the negative effects of development. This is not a battle of development versus no development. This is a chance for sustainable, smart growth to occur in Jefferson County. Truly responsible growth is achievable when coupled with long-term planning and innovative architectural and engineering techniques. We just need to calm the frenzied and sloppy approach so often seen today. The re-development of blighted brownfield properties is a wonderful opportunity and can be accomplished so long as it is done with respect to remediation of contaminants and the effect it will have on the floodplain. Communities along Five Mile Creek, Village Creek, and Valley Creek are experiencing serious flooding consequences due to past planning and engineering mistakes. Some of these mistakes will continue under this proposed Floodplain Management Ordinance. This new version of the ordinance was created without balanced input from a diverse group of stakeholders that are affected by flooding. The Floodplain Management Ordinance is just that – a plan to manage and protect new development within the floodplain, not to manage the issue at hand – floodwaters within the floodplain. Jefferson County is home to the largest city in this great state, Birmingham. The creation of a strong floodplain ordinance here will serve as a model for the rest of the state as it grows and thrives. Let us not forget: Alabama is the river state. Our rivers are our greatest asset. What we do here in Jefferson County affects all those that live downstream. For the river, Nelson Brooke Black Warrior RIVERKEEPER®