Gone in 60 Milliseconds: Trademark Law and Neuroscience

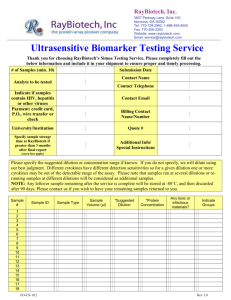

advertisement