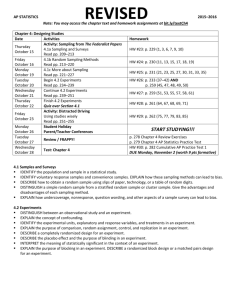

Chapter 2 – Collecting Data Sensibly

advertisement

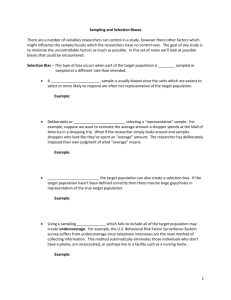

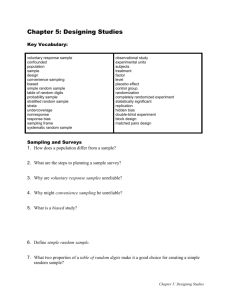

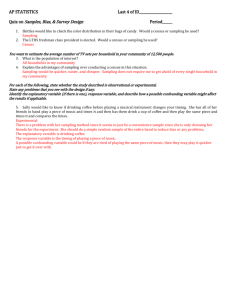

Chapter 2 – Collecting Data Sensibly 2.1 Observation and Experimentation – Observational Study – when the investigator observes characteristics of a subset of the members of one or more existing populations. The goal is to draw conclusions about the population, or about differences between 2 or more populations. There is no control over the composition of the groups and no conditions imposed, therefore it generally cannot provide evidence for a causeand-effect due to the possibility of a confounding variable. Confounding variable – Variable whose effect on the response variable cannot be untangled from the effects of treatment. Experiment – when the investigator observes how a response variable behaves when one or more explanatory variables (sometimes called factors) are manipulated. The goal is to determine the effect of the manipulated factors on the response variable. In a well designed experiment, the composition of the groups is determined by random selection and/or assignment. If an experiment is welldesigned, it can provide evidence for a cause-and-effect relationship. 2.2 Sampling Reasons for studying a sample instead of the entire population: Measuring the characteristics can be destructive. Limited resources of time and money. Bias in sampling – Is the tendency for samples to differ from the population in some systematic way. It can result from the way the sample is selected or the way information is obtained after the sample has been chosen. Type of Bias: Selection Bias (also called undercoverage) – the tendency for a sample to differ from the corresponding population as a result of systematic exclusion of some part of the population. If there is difference in the responses of the included and excluded members, that is important to the study, conclusions based on the sample are likely not valid. This can be true in the case of using volunteers or self-selected individuals. Voluntary response bias is a form of undercoverage because those with strong opinions (pro or con) are more likely to volunteer. Measurement or Response Bias – occurs when the method of observation tends to produce values that systematically differ from the true value in some way. Some causes of this are: improper measurement, wording of questions, appearance or behavior of the researcher, and lack of honesty especially when it deals with illegal, unpopular, or controversial behavior. Nonresponse Bias – Tendency for responses to differ from the corresponding population because data was not obtained from all (or a sufficient number) of the selected sample. A serious effort must be made to follow up with those in the sample that did not respond to the initial request. When deciding whether to do a mail, phone, or personal interview survey nonresponse bias is an important consideration. Random Sampling Simple Random Sample – (called a SRS for short) is a sample chosen using a method that ensures that each individual and every different possible sample of the desired size has an equal chance of being selected. It is the selection process, not the final sample, which determines whether the sample is a simple random sample. Methods of Selecting a Simple Random Sample 1) Putting names on identical slips of paper, mixing thoroughly, and then drawing them one at a time. 2) Create a numbered list of the individuals or objects (called a sampling frame) then use a table of random digits or a random number generator to select the sample. 3) With Replacement – An individual item is put back into the population after selected. This is rarely used as your sample might not consist of distinct objects or individuals. 4) Without Replacement – Once an individual is selected, it may not be selected again in the sampling process. Results in a sample of distinct objects or individuals and is more widely used. Note: If the sample size is 10% or less of the population, there is no significant difference between sampling with and without replacement Sampling Variability (or sampling error) – is the difference in the sample statistics obtained from each SRS. This difference is normal and does not indicate a poorly designed study. It is possible to obtain a SRS that is not representative of the population, but only when the sample size is very small. The random selection process allows us to be confident that the sample adequately reflects the population even when using only a fraction of the population. (See figure 2.1 p. 37) Stratified Random Sampling – occurs when the population is divided into nonoverlapping subgroups (called strata), and then a SRS is selected from each subgroup. Used most often when information about characteristics of the individual strata, as well as the entire population, is desired. A stratified random sample allows more accurate inferences than a SRS when the population is varied and the strata can provide more homogenous groups. Cluster Sampling – occurs when the population is divided into heterogenous, non-overlapping subgroups (called clusters), and then you randomly select clusters and use all individuals in the cluster. Systematic Sampling – is a procedure used when the population is a list or some other sequential arrangement. A value k is specified, and a member of the first k individuals is selected. Then every kth individual after that is chosen. Works well unless there is a repeating pattern in the population list. Multistage Sampling – occurs when multiple applications of cluster, stratified, or SRS are applied. Convenience Sampling – using an easily available or convenient group. THIS IS NOT A GOOD METHOD! Voluntary response sampling is an example of this type. 2.3 Simple Comparative Experiments Census – a study that observes, or attempts to observe, every individual in a population. Survey – a study that collects information from a sample of a population in order to determine one or more characteristics of the population. Observational Study – attempt to determine relationships between variables, but the researcher imposes no conditions. (A survey is one form of this.) Experiment – a study where the researcher deliberately influences one or more explanatory variables (also called factors) by imposing conditions and determining the effects on the response variable. This is done in order to determine the nature of the relationship between the explanatory and response variables. Design – the overall plan for conducting an experiment. A well designed experiment requires not only imposing conditions on the explanatory variable, but also eliminating rival explanations (also called extraneous factors or lurking variables) or the results will not be conclusive. Extraneous factor – a factor that is not of interest in the study, but is thought to have an affect on the response variable. Methods of dealing with extraneous factors: Direct control – make extraneous factors a constant Blocking – create groups that are similar to filter out the extraneous factors Randomization – used with confounding factors (ones that cannot be separated from the explanatory variable) that cannot be controlled or blocked to ensure that one explanatory variable is not favored over another Replication – have multiple observations for each experimental condition. 2.4 More on Experimental Design Control group- an experimental group that does not receive the treatment. Used when the purpose of the experiment is to determine if the treatment has an effect. Placebo – something that is identical (in appearance, taste, feel, etc.) to the treatment, except that it has no active ingredients. Blinding – method of denying knowledge about treatment that is used to remove preconceived notions or prevent behavior modifications. Single-blind – either the subject or the individual measuring response do not know if subject received a treatment (or which treatment if more than one.) Double-blind – both the subject and the individual measuring response do not know if subject received a treatment (or which treatment if more than one.) Experimental unit – smallest unit to which a treatment is applied 2.5 Designing Surveys Survey – a voluntary encounter between strangers in which an interviewer seeks information from a respondent by engaging in a special type of conversation. The “conversation” may be in person, over the phone, or a written questionnaire. Respondant’s tasks: Comprehend the question – questions and directions should be characterized by: 1) appropriate vocabulary for the population of interest, 2) simple sentence structure, 3) little or no ambiguity. Field-testing the questions can help greatly with this. Retrieve the information from memory – investigator should understand that most answers here are approximations of the truth and the more recent the event, the better the recall. More specific questions help with recall. Report the response – Investigator must keep in mind the effects of too many questions, social desirability bias, questions of a sensitive or threatening nature 2.6 Interpreting and Communicating the Results of Statistical Analysis Undercoverage and Overcoverage– limit our ability to generalize to the population of interest Cautions and Limitations: 1) Don’t draw cause-and-effect conclusions from observational studies 2) Don’t generalize results of an experiment using volunteers unless you can be certain the volunteers were a representative sample. 3) Don’t generalize results of an experiment using a sample unless you are sure it is representative of the population and that there are no major potential source of bias that have not been addressed. 4) Don’t generalize conclusions based on an observational study that uses voluntary response or convenience sampling.