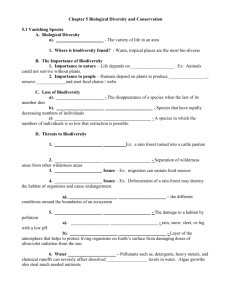

Project Document

advertisement