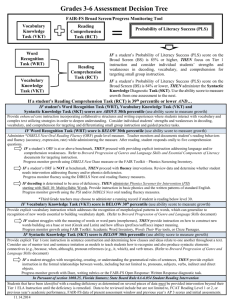

Oral Reading Fluency Benchmark Procedures and Considerations

advertisement