Serendipity in the social sciences

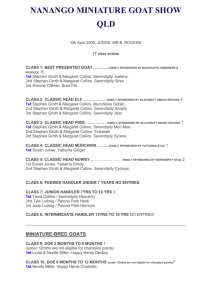

advertisement

Serendipity in the social sciences The example of law, policy and decision Danièle Bourcier Director of Research at CNRS Centre for Research in administrative and political sciences University of Paris 2 Abstract 1. Serendipity is "the ability to discover, invent, create or imagine something new without having sought, from the observation and correct interpretation of unexpected events." It relates to science but also art, law, politics and more generally human decisions. I will emphasize these areas in my presentation. 2. The works of P. van Andel show that this universal phenomenon was particularly commented on in the field of science and technology. However, in the social sciences, serendipity has a more diffuse status for several reasons: a) unlike the “hard” sciences, the experimental method or empirical approach is not the traditional heuristic of the humanities; b) the language, history and social interactions play an important role in the interpretation of events; c) the sole explanation of an unexpected event is rare and the hope of its reproducibility and falsifiability can be vain. R.K Merton, a sociologist of science, was one of the first researchers to systematically analyze the value of serendipity in social sciences and to take cases of serendipity in his own discipline. Other disciplines have provided examples equally relevant: in Psychoanalysis, Freud is quoted by his biographer Jones as having "practiced" serendipity in its main findings (interpretation of dreams). In Ethnology, methods of participant observation or the concept of acculturation have been "invented" as a result of unexpected events. Linguistics, demography, Web sciences use the concept of serendipity to explain evolutionary phenomena. 3. As a lawyer, I tried to see how serendipity could explain some unexpected phenomena in the application of laws and standards. And political assemblies pass laws that target but this target is often missed because the actors interpret the legal norm and interact with different interests. The law gradually changes direction and becomes the product of collective and dynamic interpretations. Some incentive policies (tax law or social law) eventually produce unexpected and even perverse effects. I will mention some of these cases. In conclusion, I encourage students in all disciplines interested in the phenomenon of serendipity. Serendipity is present even in the sciences called "soft": it favors the observation, and empirical approach. It learns to pay attention to emerging and dynamic phenomena in society. It requires thinking outside causality and to look at complexity positively. Finally, it unifies the methods of discovery among the sciences by returning to the concept (known in the Enlightenment) of universal science.