lecture 6: The Emergence of a National Literary Culture

advertisement

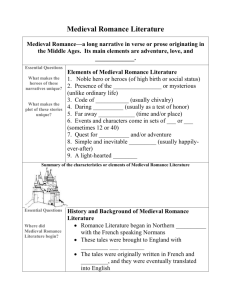

lecture 6: The Emergence of a National Literary Culture Critical material the lecture is based on Joan Dayan: “Romance and Race.” The Columbia Literary History of the United States. 89-109. Terence Martin: “The Romance.” The Columbia History of the American Novel. 72-88. American cultural anxiety in the first quarter of the 19th century: America as a cultural colony of England? In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book? or goes to an American play? or looks at an American picture or statue? Literature the Americans have none—no native literature, we mean. But why should the Americans write books, when a six weeks’ passage brings them, in their own tongue, our sense, science and genius, in bales and hogsheads? Prairies, steamboats, grist-mills are their natural objects for centuries to come (the Rev. Sidney Smith in The Edinburgh Review, 1820). - American attempts to establish a national culture and a national literature - writers of fiction face an environment basically distrustful of fiction-writing; their situation further complicated by lack of copyright regulations in America (pirating the works of English authors) Romance as the dominant fictional genre in antebellum America romance vs. novel - introducing generic distinction between romance and novel: William Congreve: “Preface” to Incognita (1692); Clara Reeve: The Progress of Romance (1795) (N: events of familiar nature, R: the wondrous and the unusual) - the “romance” gains prominence in early 19th-century fiction familiarizing the specifically American experience of westward expansion and racial contact - the larger historical context: empire-building (Cooper) and chattel slavery (the latent context of the works of Poe) - the romance as a substitute for the national epic: William Gilmore Simms: “Preface” to The Yemassee (1835) - the dominant fictional genre at the time: historical fiction (Walter Scott); popular fiction in the sentimental and gothic modes - the romance unites such distinct elements as historical exploration, psychological analysis, sentimentality, the gothic A) The Romance of the Frontier James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) - reversed the emphases of the Enlightenment civic-humanist paradigm (“fictionalized” history) The Leatherstocking Tales (published. between 1823-1841); in chronological order of the plot: The Deerslayer (1841), The Last of the Mohicans (1826), The Pathfinder (1840), The Pioneers (1823), The Prairie (1827) - historical fiction inspired by the American past (French and Indian wars, settlement of the frontier, the Lousiana Purchase) ; the distinctive American experience of racial contact with Native Americans - portrayal of Indians: relatively authentic; yet polarized along ethnic lines (good vs. bad Indian: Delawares vs. Hurons throughout the Leatherstocking series, Pawnees vs. Sioux in The Prairie) - historical justification for the moral corruption of Indians (the case of Magua): association with European (French, and to a lesser extent, English) military forces The Pioneers (1823) - the plot dramatizes conflicts over property and title to land (Indian land > Effingham > Temple), settlement of the wilderness, the dispossession of the Indians and exploitation of the land - solution by conventional devices of the popular melodramatic romance: secret identity, disclosures, marriage - yet: Cooper’s keen awareness of social and racial conflict underlying territorial expansion and settlement - the death of Indian John: the vanishing” and “extinction” of Native Americans; nostalgia over the past and acceptance of the inevitability of change The Last of the Mohicans (1826) - the struggle for possession of land depends on Anglo-Americans’ ability to tame the wilderness - the wilderness appears to be beyond control / in perpetual change / scene of violence - the frontier; colonial America as a fallen world; natural beauty sullen with violence - the force and complication of history; themes of dispossession and loss Duncan Heyward (the genteel hero); Natty Bumppo, Chingachgook, Uncas Cooper’s literary achievement: the epic enterprise with national and even mythic implications B) The Imaginative Romance Washington Irving (1783-1859) - pseudonyms and personae: Jonathan Oldstyle, Geoffrey Crayon, Diedrich Knickerbocker 1819, 20 The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. 1822 Bracebridge Hall 1824 Tales of a Traveler “Rip Van Winkle” - definition of literature as a self-serving activity (Rip’s preference for hunting, walking, storytelling) - the role of creative imagination in a society where attention is centered on material progress - the marginalization of the artist in American society - the sense of loss implicit in America’s commitment to the present and future while neglecting the past - the need to establish a specifically American historical context (Rip as a storyteller) also: distrust for the rhetoric of rapid social change and progress (the Union Hotel, the bilious orator); exposing the chaotic situation after Independence “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” - the acquisitiveness of the Yankee (Ichabod Crane’s dreams and desires) - ideology justifying westward expansion gaining momentum; Irving’s satire of new England mentality (Crane the schoolteacher and village intellectual; his career as journalist and “justice of the Ten Pound Court”) Tales reflect Irving’s need to create a world of the imagination, “a world elsewhere” (see also: Hawthorne: Salem; Thoreau: Walden; Melville: the ocean; Twain: the Mississippi; Faulkner: Yoknapatawpha) Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) prose - Poe’s “Marginalia”: [the tales are] “place[s] of imagination”; “fancies” on the “borderground” btw. sleep and wakefulness; reveal “a glimpse of the spirit’s outer world” - commitment to the imagination; empowerment of narrators who speak “supernal worlds” into being 1838 The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, novel 1840 Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque - unreliable / mad narrators (“The Cask of Amontillado,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Black Cat”) - experience beyond the range of the empirical: “a glimpse of the spirit’s outer world” (“Ligeia”) - tales of “raciocination” (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Purloined Letter”) - caricature and distortion: “King Pest,” “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” “Hop-Frog”) - parody (“A Predicament,” “How to Write a Blackwood Article”) - militantly antididactic; antidomestic (denies the most cherished 19th-century social and cultural conventions) - Poe as a Southerner: on the surface, ignores issues of race and chattel slavery; the problem, however, is latently present in modes and themes of his fiction: the gothic; obsession with the body (from erotic fascination to perversity, death and decomposition of the body, the body in jeopardy); manifestations of extreme authority “The Fall of the House of Usher” - psychological gothic; effect deriving by the conventional motifs of the gothic (the house of decay, the themes of death and incest, the atmosphere of haunting and mystery) and the structural elements of the story (mirroring— house and tarn, the house and Roderick Usher, Madeline and Roderick) - the poem “The Haunted Palace” embedded in the narrative reproduces, as a microcosm, the theme of the story - narrator positioned both inside and outside of the represented world: tight control of narrative, and credibility “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” - proto-detective story; Poe’s statement on the triumph of the rational mind over popular irrationality - the hero (Dupin) embodies the type of intellectual Poe himself represented: the reclusive genius at odds with the spirit of his time, but rising above it through the power of his mind - the orangutan, by its unreasoning and unchecked violence, represents the essentialized characteristics of the racial Other (mid-19th-century racial stereotypes) Poe’s Southern sensibility - the institution of slavery inspires the gothic mode: unchecked exercise of power over human beings; fascination with the body; anxieties about the possibility of slave rebellion