First Lady Project - American Studies @ The University of Virginia

advertisement

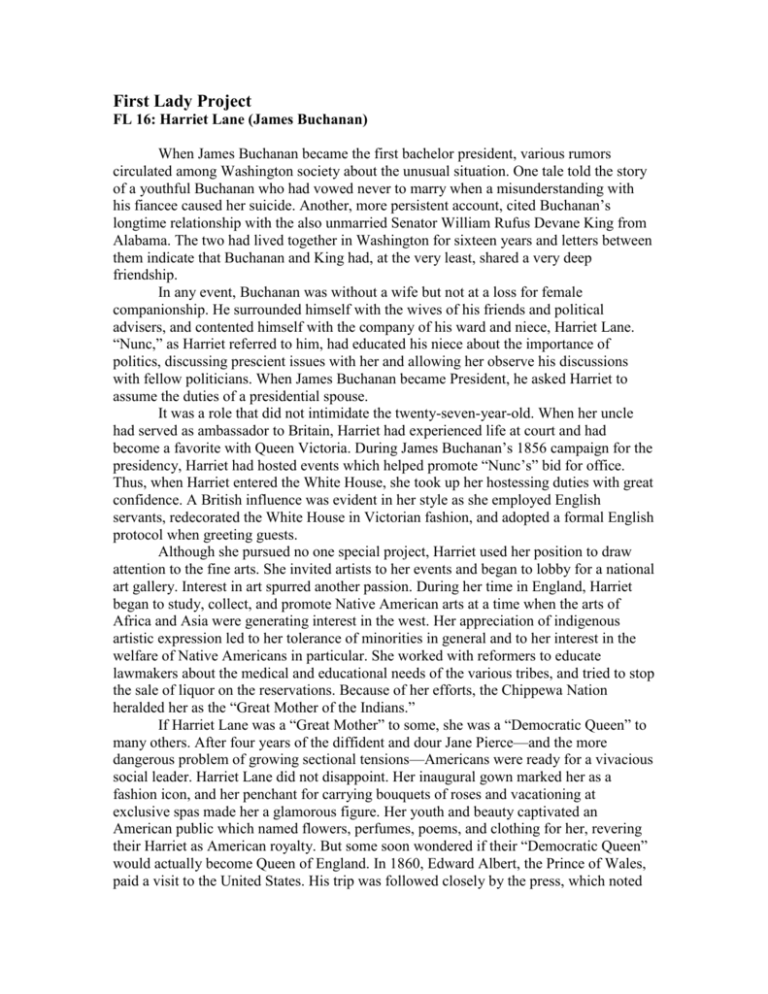

First Lady Project FL 16: Harriet Lane (James Buchanan) When James Buchanan became the first bachelor president, various rumors circulated among Washington society about the unusual situation. One tale told the story of a youthful Buchanan who had vowed never to marry when a misunderstanding with his fiancee caused her suicide. Another, more persistent account, cited Buchanan’s longtime relationship with the also unmarried Senator William Rufus Devane King from Alabama. The two had lived together in Washington for sixteen years and letters between them indicate that Buchanan and King had, at the very least, shared a very deep friendship. In any event, Buchanan was without a wife but not at a loss for female companionship. He surrounded himself with the wives of his friends and political advisers, and contented himself with the company of his ward and niece, Harriet Lane. “Nunc,” as Harriet referred to him, had educated his niece about the importance of politics, discussing prescient issues with her and allowing her observe his discussions with fellow politicians. When James Buchanan became President, he asked Harriet to assume the duties of a presidential spouse. It was a role that did not intimidate the twenty-seven-year-old. When her uncle had served as ambassador to Britain, Harriet had experienced life at court and had become a favorite with Queen Victoria. During James Buchanan’s 1856 campaign for the presidency, Harriet had hosted events which helped promote “Nunc’s” bid for office. Thus, when Harriet entered the White House, she took up her hostessing duties with great confidence. A British influence was evident in her style as she employed English servants, redecorated the White House in Victorian fashion, and adopted a formal English protocol when greeting guests. Although she pursued no one special project, Harriet used her position to draw attention to the fine arts. She invited artists to her events and began to lobby for a national art gallery. Interest in art spurred another passion. During her time in England, Harriet began to study, collect, and promote Native American arts at a time when the arts of Africa and Asia were generating interest in the west. Her appreciation of indigenous artistic expression led to her tolerance of minorities in general and to her interest in the welfare of Native Americans in particular. She worked with reformers to educate lawmakers about the medical and educational needs of the various tribes, and tried to stop the sale of liquor on the reservations. Because of her efforts, the Chippewa Nation heralded her as the “Great Mother of the Indians.” If Harriet Lane was a “Great Mother” to some, she was a “Democratic Queen” to many others. After four years of the diffident and dour Jane Pierce—and the more dangerous problem of growing sectional tensions—Americans were ready for a vivacious social leader. Harriet Lane did not disappoint. Her inaugural gown marked her as a fashion icon, and her penchant for carrying bouquets of roses and vacationing at exclusive spas made her a glamorous figure. Her youth and beauty captivated an American public which named flowers, perfumes, poems, and clothing for her, revering their Harriet as American royalty. But some soon wondered if their “Democratic Queen” would actually become Queen of England. In 1860, Edward Albert, the Prince of Wales, paid a visit to the United States. His trip was followed closely by the press, which noted that the couple toured Mount Vernon, danced together, and played games of tenpins. The prince’s visit, as well as Harriet’s favorable relationship with Queen Victoria, made Americans wonder if Harriet ultimately would leave the White House for the grander surroundings of Buckingham Palace. But even as Harriet entertained English royalty, she was more than a social hostess for her uncle. She was also James Buchanan’s political partner. Harriet attended cabinet meetings and felt free to offer her advice. Buchanan clearly appreciated Harriet’s role and accorded her all the prestige enjoyed by a presidential spouse, without requiring her to adopt the demands of protocol and etiquette. Despite the pair’s closeness, the relationship at times grew strained. Harriet never appreciated having to entertain suitors with “Nunc” looking on, and resented Buchanan opening her mail. Harriet’s discontent was evident when, in 1859, she took a three-month summer vacation from the capital and the President. Despite their differences, Harriet was an important source of support during the sectional crisis. Critics censured Buchanan for allowing southern states to secede following Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 election. But even as Harriet offered “Nunc” comfort, she encountered attacks as well. Detractors accused her of spending too much redecorating the White House, of using a naval ship for her own personal use, of stealing White House portraits, and of convincing England to remain neutral instead of siding with the Union when the South seceded. Harriet, like most Americans, had been aware of the increasing tensions in the country. It appears that she privately opposed slavery and southern secession, though she worried about the country’s economic future if the “peculiar institution” was abolished. Publicly, however, she remained silent on the issue of slavery and insisted that her guests follow her example. Her social skills began to serve a political purpose as she manipulated complex seating arrangements at dinner parties and entertainments, keeping political foes apart and dispensing equal favor to all. Unfortunately, her efforts at keeping the peace at White House social gatherings translated neither into a smooth presidency for her uncle nor peace for the nation. Indeed, the commencement of the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln’s valiant struggle to save the Union, as well as the shrewishness of Mary Todd Lincoln, have tended to eclipse both the presidency of James Buchanan and the tenure of Harriet Lane as well. Sources: Anthony, Carl Sferrazza, First Ladies: The Saga of the Presidents’ Wives and Their Power, 1789-1961 (New York: Quill), 1990. Watson, Robert P., First Ladies of the United States: A Biographical Dictionary (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 2001. www.whitehouse.gov/history/firstladies