early and partial Article 76 implementation:

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

An investigation of the feasibility of making an early initial claim to part of

Canada’s juridical continental shelf under Article 76 of United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

David Monahan

Dave Monahan

Director, Ocean Mapping

Canadian Hydrographic Service

615 Booth St

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

KIA 0E6

Phone (613) 992-0017, secty 995-4666

Fax (613) 996-9053 and

Ocean Mapping Group

Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering

University of New Brunswick

P.O. Box 4400, Fredericton, NB E3B 5A3

Phone (506) 453-5147

Fax (506) 453-4943

Email monahand@DFO-mpo.gc.ca and

Abstract

The United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) divides the floor of the oceans into zones that fall under the jurisdiction of either a Coastal State or of the UN. Coastal States are automatically given an Exclusive Economic Zone

(EEZ) 200 nautical miles wide, and need take no action. Beyond the EEZ,

Canada and another 50 to 60 states may be able to claim jurisdiction over the seafloor of the juridical continental shelf, but will have to undertake some possibly extensive preparation, prepare a claim, and submit it to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). The work required to do this may be time consuming and require a high degree of sophistication; an unpublished

Federal Government document estimates that preparing the entire Canadian claim from new data will require 8 to 10 years and cost between $60 and $100 million dollars.

15/04/20 1 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

No state has as yet submitted a claim, but it can be assumed that those who intend to do so with new data will be subject to costs proportional to the area they wish to claim. Such potential spending represents opportunities for Canadians in employment, training, research and the provision of goods and services, both domestically and abroad. Several counties have already sought help from

Canada (e.g. Ireland, NZ, Uruguay), without us marketing our expertise, yet it is countries like the UK who are expending effort on establishing themselves as the source of UNCLOS expertise. Canada can counter this thrust, but only if we act promptly.

Although the position Canada holds in the perception of many Coastal States who may prepare a claim is strong because of our diplomatic and scientific involvement in UNCLOS to date, our position is weakened through not having ratified. This paper develops an approach that can help circumvent this argument as well as substantially advancing Canada’s economic opportunities through proposing that Canada prepare a claim to a portion of our continental shelf, and submitting that claim to the UN. This can be done in one of two ways. The first would involve collecting new data specifically for the claim: this would probably take two years at a cost of less than $5 million. The second would be to use existing data and make the best possible claim based on it: this could probably be done as a “desk study” within six months. Moving quickly can mean Canada is the first to submit a claim, solidifying our weakening leadership position and strengthening the appeal of Canadian expertise that can be sold to other countries. Doing so will also lead to a stronger final Canadian claim.

This paper examines the issues involved in claiming a limited portion of the

Canadian continental shelf under Article 76 of UNCLOS within two years, and recommends that a Partial Claim be prepared.

15/04/20 2 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 4

2. The claiming process ..................................................................................... 5

2.1 Preparation of a claim by a Coastal State ................................................. 6

2.2 The Formal process of submitting a claim ................................................. 7

1 Bringing a submission to the Commission ................................................ 7

2 Establishment of a subcommission ........................................................... 7

3 Activities of the subcommission ................................................................ 7

4 Finalization of the outer limits .................................................................... 8

3. The Concept of Claiming Piecemeal .............................................................. 8

4.Benefits derived from preparing a Partial Claim .............................................. 8

4.1. Allows deeper analysis of the CLCS Guidelines ...................................... 9

4.1.1 Possible Outcomes ............................................................................. 9

4.2. Permits testing, analysis and verification of existing mapping capabilities

...................................................................................................................... 10

4.2.1 Possible Outcomes ........................................................................... 10

4.3. Allows testing, analysis and verification of accuracy and completeness of data sets ....................................................................................................... 10

4.4. Enables CARIS LOTS Testing with real data ......................................... 11

4.4.1 Possible Outcomes ........................................................................... 11

4.5. Permits testing, analysis and verification of methodologies for finding

Foot of the Slope and the Gardener (sediment thickness) line ..................... 12

4.5.1 Possible Outcomes ........................................................................... 12

4.6 Permits the development of improved Cost estimates for preparing a

Complete Claim ............................................................................................ 12

Table 1 Comparison of costs for increasing levels of effort required to prepare a claim.

...................................................................................... 13

4.6.1 Possible Outcomes ........................................................................... 14

5.Advantages derived from submitting a Partial Claim ..................................... 14

5.1. Advantages to Canada as an exporter of goods and services ............... 14

5.2. Advantages to Canada in diplomatic / legal circles ................................ 15

6. Examination of the feasibility of Canada submitting a Partial Claim ............. 16

6.1 The possibility of any state making a Partial Claim ................................. 16

6.2 The possibility that a state that has not ratified can submit a claim ......... 17

6.3 Initial and subsequent partial claims and precedents set ........................ 18

6.4 Timing Considerations ............................................................................ 19

6.5 Risk Analysis ........................................................................................... 20 a.

CLCS will not consider claim ................................................................ 20 b. The claim will be examined and found to be deficient ............................ 20 c. Claim will later be found to be smaller than could have been claimed ... 21

7. Approaches to preparing a Partial Claim ..................................................... 21

Table 2 Summary of steps in scenarios of increasing levels of complexity from no data collection to considerable data collection ........................... 22

8. Selection of geographic area to be claimed ................................................. 23

8.1 Imperative characteristics of area selected ............................................. 23

15/04/20 3 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

1. Must fall within the ambit of the CLCS.

.................................................. 23

2. Must be covered by an appropriate amount of data.

............................. 23

3. Must test the Guidelines in a credible fashion.

...................................... 23

Table 3. Tentative cheme for assigning numerical coding to complexity of continental slopes over which a claim might be made.

........................... 24

4 Must provide the advantages discussed in Section 4.

............................ 24

5 Must be able to yield a Partial Claim in a form suitable for submission in a short period of time.

................................................................................... 24

8.2 Candidate Areas ..................................................................................... 24

Table 4. Analy sis of Canada’s three oceans suitability for a Partial Claim.

................................................................................................................ 25

8.3 Comparison of areas ............................................................................... 25

Figure !. Candidate areas for Partial Claim in Atlantic.

............................ 26

Table 6. Evaluation of condidate areas against steps in preparing a claim.

................................................................................................................ 27

Table 7. Weighing the wants/benefits of the candidate areas.

................ 29

9 Decision Analysis .......................................................................................... 29

9.1 Recommendation One: To prepare a Partial Claim or not ...................... 29

9.2 Recommendation Two: To collect new data or not ................................. 30

9.3 Recommendation Three: Area to be used .............................................. 30

10. Plan for next phase, if there is to be one .................................................... 31

11. Summary .................................................................................................... 31

References cited in text ................................................................................... 32

Appendix 1 Iterative model for preparing a claim ............................................. 35

Appendix ll Coastal States who have ratified UNCLOS, who have the possibility of an extended claim, and who are likely to consider Canada as a source of some form of help.) .......................................................................................... 36

1. Introduction

Signed in 1982 as the culmination of more than ten years of work, in 320 Articles

UNCLOS (United Nations, 1983) attempts to regulate how humanity conducts itself in the world's oceans and seas. The Convention came into force in 1994 after ratification by sixty countries: to date, 133 countries have ratified. Canada signed the Convention in 1982 but has not yet ratified.

The section of UNCLOS that this paper addresses is the preparation of a claim over the seabed of the Continental Shelf adjacent to Canada. Article 77 grants the Coastal State sovereign rights over the Continental Shelf for the purpose of exploring it and exploiting its natural resources. Article 76 defines how the submerged area over which a state can claim jurisdiction is to be determined, and establishes a process for submitting claims to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). In brief, under certain morphological and

15/04/20 4 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM geological conditions, a state may claim a continental shelf outside its 200 nautical mile-wide Exclusive Economic Zone. It is known that appropriate conditions exist off Canada in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, and that vast areas can be claimed beyond 200 nautical miles.

In a 1995, the Canadian Hydrographic Service and Geological Survey of Canada were charged with assembling and analyzing all existing data for it's suitability and completeness for use in substantiating Canada’s claim to the maximum extent possible. The Canada Oceans Act, which was passed in 1996, states that

Canada’s Continental Shelf will be “determined in the manner under international law that results in the maximum extent of the continental shelf of Canada.”

The two groups were also tasked with preparing and continually updating a plan for any data collection and surveying activities necessary to rectify any deficiencies in the existing data.

The costs associated with the plan are contained in Section 4.6. In brief, Canada faces a large task because of the sheer size of the Canadian continental shelves, because of the exceptional difficulty in accessing the Arctic seafloor from surface ships, because each shelf contains areas that will not be straightforward, and because of the plethora of new data that will be required. Preparing a claim that would encompass all of Canada’s waters could take as long as 8 to 10 years and cost between $60 and $100 million. This work will not only be valuable for Law of the Sea purposes; the collected data will become part of the national data infrastructure where it will be used for other applications, and for providing training and employment opportunities.

This paper suggests and describes an interim step toward preparation of a complete claim over all Canada’s continental shelf, one that results in some immediate gains for Canada. The project would consist of preparing and submitting a claim for a portion of the Canadian shelf, hereafter referred to as a

“Partial Claim”.

2. The claiming process

Within ten years of a State ratifying the Convention, or for early ratifiers, within ten years of the Convention coming into force (i.e. by 2004), a Coastal State must submit to the CLCS the proposed limits to its Continental Shelf, together with supporting evidence. (The CLCS is established under Annex II of the

Convention). Naturally, a great deal of preparatory work was done in anticipation of the specific demands for evidence and data that the CLCS was expected to make. An elaboration of these demands was not immediately forthcoming, since the members of the Commission were not elected until March, 1997, and the work required to issue “Guidelines” on the quantity and types of data needed to support a claim was not finished until May, 1999. (United Nations, 1999) The

CLCS also produced Modus Operandi (United Nations, 1997) and (Rules of

Procedure United Nations, 1998a) documents that elaborate some logistics of the claiming process.

15/04/20 5 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

This paper breaks the description of this activity into two stages, the preparation of a claim by a Coastal State and the formal process of submitting a claim

2.1 Preparation of a claim by a Coastal State

Several models for the process to be followed in preparing a claim have been advocated, including United Nations 1993, United Nations, 1999, Macnab 2000,

Smith and Taft, 2000. These are largely descriptive and contain little guidance as to the sequence to be followed. Additionally, they largely ignore the effect of increasing scale as the case is developed. In an attempt to overcome these deficiencies, Monahan et al , 1999 developed an iterative model of the claiming process. It begins with examining an area on small-scale, publicly available maps and cycles through increasing amounts of data and increasingly complex continental margins. It addresses the issue of where strict application of the rules does not provide a solution and judgmental elements must be introduced. A flow chart of this model is included as Appendix 1.

Generally, a State wishing to prepare a claim must carry out the following activities: a) prepare base maps for the exercise b) Map baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured c) Map the 2500m depth contour

d) Map the Foot of the Slope e) Map sediment thickness f) Determine the geological nature of isolated elevations g) Decide on the case for ‘evidence to the contrary’ h) Create lines at calculated distances. (60, 100, 200 and 350nautical miles) i) Prepare data bases of the above j) Prepare output in the form of charts, maps and diagrams

These are only the technical steps of preparation. There must be a concomitant effort by the diplomatic corps if the claim is submitted.

15/04/20 6 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

2.2 The Formal process of submitting a claim

The following is condensed from Annex ll of UNCLOS (United Nations, 1983), the

Guidelines (United Nations, 1999), Modus Operandi (United Nations, 1997) and

Rules of Procedure (United Nations, 1998a).

1 Bringing a submission to the Commission

The Coastal State submits particulars of the limits it intends to claim along with supporting scientific and technical data to the Secretary-General of the United

Nations. The SecretaryGeneral “shall... promptly notify the Commission and all members of the United Nations... of the receipt of a submission, and make public the proposed outer limits of the continental shelf “. The submission shall be included in the agenda of the next meeting of the CLCS that occurs more than three months after the date of the publication by the Secretary-General of the proposed outer limits. (In effect, this gives other states at least three months in which they can examine the proposed outer limits.) The CLCS meets

“at least once a year and as often as is required for the effective performance of its functions”; conceivably then, a submission could languish for almost fifteen months before being addressed, but this is unlikely. At the meeting of the CLCS there will be a presentation of the submission by Coastal State representatives, which will include Charts indicating the proposed limits, the criteria of article 76 which were applied, names of any members of the Commission who acted as advisers and any dispute arising from the submission. The submission is now formally before the CLCS.

2 Establishment of a subcommission

After hearing this presentation and unless it decides otherwise (and nowhere is it specified how or why the CLCS might decide otherwise), the CLCS shall establish a subcommission for the consideration of each submission. The subcommission will be composed of seven CLCS members, who cannot be nationals of the Coastal State making the submission or have assisted the

Coastal State by providing scientific and technical advice. When the subcommission meets, the Coastal State shall be invited to send its representatives to participate, without the right to vote.

3 Activities of the subcommission

The subcommission will examine whether the format of the submission is in compliance with the Guidelines, and will ensure that all necessary information is included in the submission. It may request the Coastal State to correct the format or to provide any other information or clarification. The subcommission may decide that it needs the advice of specialists concerning the submission.

15/04/20 7 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

The subcommission will conduct a technical evaluation of the submission, beginning with verification of which criterion or criteria specified in article 76 is/are used. Next, the subcommission will undertake an analysis of the submitted data in order to verify:

“(a) Whether the coordinates were established from primary sources, or from other sources;

(b) The validity of all coordinates;

(c) That no segment in the delineation is longer than 60 nautical miles; and

(d) That the data submitted are sufficient in terms of quantity and quality to justify the proposed limits.” (United Nations, 1997, paragraph 12.2)

If the subcommission thinks there is a need for more data or information, the

Coastal State will provide the required data or information within the time period specified by the subcommission.

The subcommission will prepare recommendations and submit them in writing to the Commission.

4 Finalization of the outer limits

The recommendations of the Commission on the outer limits of the continental shelf shall be submitted in writing to the Coastal State. If the Coastal State accepts the recommendations, it shall deposit with the Secretary-General charts and relevant information permanently describing the outer limits of its continental shelf. The Secretary-General shall give due publicity thereto. In the case of disagreement by the Coastal State with the recommendations of the

Commission, the Coastal State shall make a revised or new submission to the

Commission and the cycle starts again.

Note

– the process as described in this section is the model to be followed where there are no disputes between opposite or adjacent states. That case is discussed under Section 6.

3. The Concept of Claiming Piecemeal

Simply stated, the concept is to prepare a claim for a part of the Canadian continental shelf, submit that claim to the CLCS and have the claim approved.

4.Benefits derived from preparing a Partial Claim

15/04/20 8 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

4.1. Allows deeper analysis of the CLCS Guidelines

Representatives of over 150 states prepared the Convention working over 12 years under rules of consensus. Consequently, in places its wording may require some flexibility in interpretation. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Article 76, a fact clearly recognized by the framers of UNCLOS who established the

Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to examine claims of

Coastal States and recommend their acceptance or rejection. The Coastal State will undoubtedly accept a recommendation that agrees with their submission, in which case the limits are deposited with the Secretary-General of the UN. If the

CLCS recommends rejection, the Coastal State can modify its claim and resubmit.

The CLCS was elected in March, 1997 and in September, 1998 released

Provisional Guidelines (United Nations, 1998b) outlining their interpretation of what Article 76 was asking for, as well as listing their requirements for data types, quantities and standards. As a provisional document, the Guidelines were circulated to Coastal States, to International groups such as ABLOS, and to individual experts. Feedback from some of these was used to modify the text and the Guidelines were issued in “Final’ form in May 99, 1999. The three stages of initial drafting, critical review, and re-writing were abstract exercises with the participants restricted to concepts with general application not applied to any particular part of the seafloor. The CLCS itself was very loath to do so since it might prejudice the claim of the Coastal State that may want to claim the area used for the test. Unfortunately, this leaves states with potential claims in the position of not having any real precedents to follow when preparing their case.

Following a suggestion of Wells (personal communication, 1999), the author proposed (May 2, 2000) to the Commission that an artificial piece of geography that contained all the elements of a continental shelf be created, and a “claim” be prepared on it by the CLCS itself. If this process were to take place in public, submitting states would have some valid information on which to base their planning and preparations. Peter Croker, the Irish Commissioner, was generally positive and suggested that the Commission might even want to include this with training material. However, there was not broad support within the Commission.

The Partial Claim concept espoused in this paper can be used in a similar manner, testing the wording of the Guidelines, with the advantage of using a real piece of geography and real data.

4.1.1 Possible Outcomes a) Unearthing of weakness or contradictions in the Guidelines b) Deeper appreciation of where data collection and analysis might be most beneficially focussed c) Understanding of the benefit/costs of pursuing any particular path through the

Guidelines

15/04/20 9 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

4.2. Permits testing, analysis and verification of existing mapping capabilities

An unstated assumption of the Guidelines is that existing mapping techniques will be capable of providing the data and supporting material the CLCS feels is necessary to include with a claim. The Guidelines specify certain types of data that are regarded as primary, that are admissible and that are inadmissible.

Given that the continental slopes are the most poorly mapped sections of a poorly mapped ocean, and the Foot of the Slope may or may not exist, this is a shortsighted stance. It may turn out that the demands of the Guidelines cannot be met, or that they can only be met by methods not currently approved.

Within the Partial Claim project, it may be possible to determine a feature using data obtained from various ocean mapping instruments and compare these with the requirement of the Guidelines. For example, Paragraph 4.2.1. of the

Guidelines states :

“The complete bathymetric database used in the delineation of the 2,500 m isobath in a submission may only include a combination of the following data:

Single-beam echo sounding measurements;

Multi-beam echo sounding measurements;

Bathymetric side-scan sonar measurements;

Interferometric side-scan sonar measurements; and

Seismic reflectionderived bathymetric measurements.”

It may also be possible to compare results from non-approved data sources, such as satellite bathymetry (eg Smith and Sandwell, 1997)

4.2.1 Possible Outcomes a) Discovery of the inappropriateness of some of the data types required by the

Guidelines b) Unearthing of preferential bias in a technique. c) Cost comparison of results obtained by various mapping instruments. d) Development of useful combinations of data types.

4.3. Allows testing, analysis and verification of accuracy and completeness of data sets

Federal government surveying and mapping agencies, primarily the Canadian

Hydrographic Service and the Geological Survey of Canada, have collected an array of seafloor data over many years. Since 1994, some of it, primarily bathymetry, has been organized into special data bases aimed at Article 76 needs (Macnab, et al , 1996, Stark et al , 1997. There does not seem to be an equivalent effort to assemble in a coordinated form the data needed to support a sediment thickness line, although both reflection and refraction data are available piecemeal through Geological Survey of Canada (Atlantic). The bathymetric data base can be exercised in several ways, including extraction of profiles,

15/04/20 10 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM production of grids and fitting of surfaces. It also serves as a form of ‘ground truth’ against which new data of various types can be tested. Since the density of data varies within this data set, the necessary spacing and quantities of data can be examined.

Within the area chosen as part of the Partial Claim exercise, the 2500m plus 100 nautical miles line and Foot of the Slope will be produced from existing maps, from the existing SBES database, from a grid derived form the existing data, and from the new MBES data. They will be compared in several ways and the limit lines they produce will be evaluated.

4.3.1 Possible Outcomes a) Exercising of the databases prepared for Article 76 purposes. b) Uncovering of any areas where data is incomplete. c) Examination of the accuracy of the data and the means of preparing the error estimates required by the Guidelines. d) Determination of how multibeam data can be incorporated coarser SBES data. e) The return, in terms of area gained, of building a national data set as opposed to simply using one of the public domain data sets can be established. f) The impact of grid size may be evaluated g) The effect on the outer limit of adding extra data points may be shown through the different data densities. h) The impact of orientation of slope relative to grids or tracks may be shown. i) The different contours produced from the different data sets can be compared to give an estimate of the areas that may be ‘gained or lost’ by using different data densities, data sets, or techniques. (The area “at risk”).

4.4. Enables CARIS LOTS Testing with real data

CARIS Universal Systems Limited, the Geological Survey of Canada, and the

Canadian Hydrographic Service have collaborated to develop LOTS, a selection of software procedures tailored to satisfy the data handling and management requirements of Article 76. (Halim et al , 1999, van de Poll et al , 2000) LOTS offers a full range of operations designed to minimize the tasks associated with data handling, and to focus on data analysis. Its design goal was to allow the development and display of a range of potential outer limit scenarios, and to select the most advantageous configuration. LOTS has been tested on public domain data, which is generally at a small scale / low level of detail (Monahan and Mayer, 1999), and can benefit from being more rigorously tested against real data. Preparing a Partial Claim could achieve this end.

4.4.1 Possible Outcomes a) Rigorous testing of LOTS ability to input and process real data

15/04/20 11 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM b) An evaluation of the training needed/ learning curve to use the software c) Demonstration of the graphic output that could go into a claim d) Bringing LOTS officially to the examination (and hopefully endorsement) of the

CLCS (they have right to examine all software and data sets used)

4.5. Permits testing, analysis and verification of methodologies for finding Foot of the Slope and the Gardener (sediment thickness) line

It may be possible to compare the results obtained from various methods of interpretation of the Foot of the Slope and sediment thickness lines, and compare these with the requirement of the Guidelines. For example, comparing the results for finding the Foot of the Slope from two-dimensional bathymetric profiles with three-dimensional techniques, e.g. finding maximum change on two-dimensional profiles vs. surface fitting (Vanicek et al , 1994, Bennett, 1998.) can lead to a selection or development of a rigorous technique that is defensible before the

Commission. The Commission has stated approaches that it will not accept, or accept alone, and the Guidelines mention a number of possible approaches the

Commission will accept while still “remaining open to other”. It will require explanations of whatever techniques were used. Since different approaches will produce different amounts of territory that could be claimed, and since Canada wishes to maximize its claim, a number of approaches can be tested and the area they produce compared.

4.5.1 Possible Outcomes a) An evaluation of methods in terms of the horizontal differences in results they produce. b) An assessment of the type of data required to satisfy each method. c) Production of an optimal approach to finding Foot of the Slope and sediment thickness.

4.6 Permits the development of improved Cost estimates for preparing a

Complete Claim

The costs of preparing a claim will vary with several factors, including size of area, complexity of sea floor, accessibility by survey platforms, amount of data already available, amount of new data required, and which formulae and constraints of Article 76 are invoked. These can vary within a continental shelf, and do so off Atlantic Canada. Table 1 lists in ascending order of cost the options for the portions of Article 76 used. The least expensive case would be to use existing data, use the Foot of the Slope + 60 formula line with the 350nautical miles outer constraint. This assumes a relatively straightforward Foot of the

Slope, one that is easy to find and not complicated by isolated elevations separate from it. Complex Foot of the Slope situations may be impossible to resolve with existing data, and this option’s cost projection and therefore position relative to the other options in the table might rise. Adding use of the 2500m

15/04/20 12 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM contour as a constraint will probably add to the cost, especially if new data must be collected in order to delineate it completely and accurately. Foot of the Slope and 2500m contour may be determined using echo sounding (single or multi) alone: determining sediment thickness requires seismic data, and possibly a corroborating bore hole, and this type of data is much more expensive. In fact, it is not clear how seismic data can be collected in the ice-covered waters of the

Arctic. At the top of the cost scale, "evidence to the contrary" may require an entire suite of geological and geophysical evidence. (As a beginning, the

Guidelines Paragraph 6.3.10. list “Apart from drilling, sampling and coring... radiometric age dating, palaeontological age correlation, geochemical-isotope chemical analyses and palaeomagnetic studies.), and the costs of collecting and interpreting this data will be proportionally higher. An additional burden on using

"evidence to the contrary" is that the CLCS Guidelines require the claiming state to include the evidence that would have been used for a claim based on Foot of the Slope, and show that it does not apply.

Complete claim - Atlantic Complete claim - Arctic Partial Claim

Factor Based On formula Foot of the Slope +60 M constraint 350 nautical miles constraint

Existing data New data Existing data New data Existing data New data low

0

5M

0 impossible 24M

0 free

0

1M

0 formula Foot of the Slope +60 M constraint 2500m plus 100 nm constraint formula sediment thickness constraint 350 nautical miles constraint low

?

0

5M

5M

16-32M

0

24M

?

?

0 free free

0

1M

3M

0 formula sediment thickness constraint 2500m plus 100 nm constraint formula "evidence to the contrary" constraint 350 nautical miles constraint formula "evidence to the contrary" constraint 2500m plus 100 nm constraint

?

?

0

?

16-32M

5M

?

0

?

5M

?

?

0

?

? free

?

0

?

0

3M

?

0

?

Table 1 Comparison of costs for increasing levels of effort required to prepare a claim.

A state might be tempted to use the cheapest route and make a submission based only on Foot of the Slope +60 using existing data. This would outline an area of continental shelf, although it might not be as large as could be claimed using new data or using sediment thickness. At risk is the loss of the territory between the Foot of the Slope + 60 and the sediment thickness formula line, and the magnitude of this will not be known unless a sediment thickness line is developed. It is possible that the sediment thickness line will be landward of the

Foot of the Slope +60 line, and no area would be added to the continental shelf.

Clearly a state will want to investigate this before launching a seismic exploration program.

Within Article 76, paragraph 7 might effect costs. “The Coastal State shall delineate the outer limits of its continental shelf,... by straight lines not exceeding

60 nautical miles in length, connecting fixed points, defined by co-ordinates of latit ude and longitude.” Although this means that in theory the formula lines need

15/04/20 13 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM only be measured at points 60 nautical miles apart Coastal States wishing to ensure that they get the most territory possible will have to collect more than the absolute minimum amount and type of data. A number of groups in other countries are recommending that the minimum distance between survey lines be

30 nautical miles to give a proper outer limit line of 60 nautical miles segments,

There have been a number of estimates of the costs to Canada for preparation of a complete claim. The 1994 Cabinet Document suggested that between $60 and

$100 million would be needed, figures which included collecting seismic lines along the entire margin. Since then, data assembly efforts in the Atlantic have probably reduced the numbers, and our greater understanding that not all types of data will be required everywhere will have further reduced the estimates.

However, in the Arctic, it is still not known how some of the data will be collected, and estimates there are very conjectural. Nevertheless, a complete claim will be expensive.

Preparing a Partial Claim is subject to all the same variables, as shown in Table ccc. Since the size of the area is much smaller, the amount of data required is one tenth or less. If the data already exists then assembly will be easier and faster. Should there be a need to collect new data, then the ship time will be much shorter. A Partial Claim of a simple area already covered with sufficient existing data would mean that the Partial Claim could be prepared in approximately six person months, needing only office and computer support.

4.6.1 Possible Outcomes a) An examination of the line spacing for seismic data required for sediment thickness b) The cost/ benefit ratio of adding more data and adding new types of data can be determined. c) A better estimate of the total cost of the complete claim can be produced.

5.Advantages derived from submitting a Partial Claim

5.1. Advantages to Canada as an exporter of goods and services

Of the approximately 150 Coastal States, it is estimated that 60 have neighbors closer than 400 nautical miles preventing a continental shelf claim, another 30 have a shelf less than 200 nautical miles wide, leaving 50-60 potential claimants.

Some of the latter have appealed for help, and providing that help is a real opportunity for Canada. (Appendix ll lists those Coastal States who have ratified

UNCLOS, who have the possibility of an extended claim, and who are likely to consider Canada as a source of some form of help.) Canadian industrial opportunities range from providing software and equipment through to specifying, supervising and quality ensuring or providing complete surveys, data collection and analyses. Canadian Universities can provide training, ranging from short

15/04/20 14 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM courses to degree programs, in the many elements of preparing a claim. Other industrialized nations have realized this potential and the UK, at least, is advertising its services on the world market.

There are a number of factors that will determine how a state seeking help decides from whom to purchase it. Canada enjoys a good reputation in hydrography and marine geology/geophysics and our scientists have published extensively in the theoretical literature that addresses Article 76. CARIS of

Fredericton has developed and is selling to other countries a suite of software that can be used in preparing a claim. (Halim, 1999). The University of New

Brunswick has conducted a workshop on Article 76. (Wells, 1994). Geometrica of

Dartmouth, NS and the Law Department at Dalhousie University advise Coastal

States (Saunders, personal communication, 2000). These help place Canada in a favorable light with potential clients. However, we have not yet ratified and consequently not had a full opportunity to demonstrate our capabilities.

Furthermore, there is some negative reaction or even stigma associated with

Canada’s non-ratification.

Since no state has yet submitted a claim, the first to do so will be watched closely by all other states. Under the CLCS rules, the material making up the claim is not disclosed by them to the public domain, only the results. Knowledge of how the

Commission reacted to each piece of information will be known only to the submitting state, whose representatives will have attended the meetings of the

CLCS sub-Commission . If Canada is the first to submit we will consequently possess knowledge that could be used to our advantage in selling our expertise overseas. As the first test case, we will develop a deeper understanding of the

Guidelines than any other country, and our position as a country able to provide support to other claiming states will be greatly enhanced. The Canadian team will have gained the first practical, hands-on experience with submitting a claim, and that experience may be exportable. CARIS LOTS software will have been officially examined by the CLCS, and this can help its acceptance by other clients.

5.2. Advantages to Canada in diplomatic / legal circles

This section will have to be reviewed by DFAIT, but form discussions with them and from the author’s reasoning it is likely that the preparation of a claim, even if it is not submitted, could be beneficial. Such an act could be referred to to show that Canada is not deliberately shunning ratification of UNCLOS, and is in fact working towards it. This effect will be magnified if the Partial Claim is in fact submitted. It can help overcome any negative reaction or even stigma associated with Canada’s non-ratification. It will be multiplied many times if we are the first to submit, since although a number of countries have embarked upon survey programs, and others are in the process of defining how they will collect the necessary data, none have as yet gone through all the necessary steps and

15/04/20 15 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM submitted a claim. Should we do so first, it will place our diplomats in position to advise their foreign counterparts.

DFAIT will have to talk to the USA and France before submitting to assure them that the Partial Claim will not prejudice the boundary between them, and can use this dialogue to their advantage.

If a Partial Claim is accepted by the CLCS, Canada will have established the principal that Partial Claims may be submitted and the principal that States that have not ratified can submit a claim. Either or both should augment the stature of

Canada in the international arena. We can probably profit from having, in fact, reduced the apparent power of the Commission, whose published words have not found favor with every Coastal State.

6. Examination of the feasibility of Canada submitting a Partial Claim

There are two obvious questions to ask before Canada can pursue this course.

One is whether a State can make a partial submission to the Commission, the other is whether a state that has not ratified the Convention can submit a claim.

6.1 The possibility of any state making a Partial Claim

At the first “Open Day” held by the CLCS (May 1 st , 2000), one of the most frequently asked question was whether a partial submission can be made. A number of national representatives expressed strong favour of partial claims and the delegate from Australia went so far as to state that Australia would be submitting partial claims for some of its isolated islands. In their responses, it was clear that the current CLCS does not want this to become the generally used method, primarily because of the extra expense and time that they foresee being required. Many attendees clearly wanted this and left the impression that they would address the issue to the States Parties. (Canada is not a State Party)

Article 76 paragraph 8 says simply “Information on the limits of the continental shelf ...shall be submitted by the Coastal State to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf”. There is nothing in these words that offer any instruction on how the information is to be submitted: they do not demand a single submission nor prohibit a multiple one. Annex ll of UNCLOS, which establishes the CLCS, makes no reference to submissions including partial or complete areas, nor do the Guidelines or Modus Operandi of the Commission.

The Rules of Procedure do refer to partial submissions in ANNEX I, Submissions

In Case Of A Dispute Between States With Opposite Or Adjacent Coasts Or In

Other Cases Of Unresolved Land Or Maritime Disputes. This Annex begins by reminding its readers that the CLCS has no authority over disputes between

States. It goes on to include in Paragraph 3

15/04/20 16 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

“ A submission may be made by a Coastal State for a portion of its continental shelf in order not to prejudice questions relating to the delimitation of boundaries between States in any other portion or portions of the continental shelf for which a submission may be made later, notwithstanding the provisions regarding the ten-year period established by art icle 4 of Annex II to the Convention.”

Clearly this section allows, even encourages, partial claims in cases of dispute. If

Canada submits a claim south of Nova Scotia extending westward, that claim will abut the USA south of the present Gulf of Maine award line. The extension of that line will have to be made before the boundary can be resolved, but the

Commission has no authority to rule on it. Canada can argue that it has an unresolved boundary with the USA and is thereby entitled to submit a partial claim under paragraph 3 of Annex ll of the Rules of Procedure.

The above is merely the logical interpretation of the words of the Convention and supporting documentation. In reality, the question will be answered by the practices of professional diplomats. To determine their reaction, the author consulted with his counterpart in Department of Foreign Affairs and International

Trade (DFAIT) and received the following answer: “...nothing in UNCLOS or the rules prevents a State from making a submission that covers only a part of its continental shelf. We think that Canada can make a partial submission to the

Commission and that it is unlikely that this would be contested by other States.”

(Strauss, personal communication, 2000).

6.2 The possibility that a state that has not ratified can submit a claim

The author has briefed staff of the Department of Foreign Affairs and

International Trade (DFAIT). They were warm to the entire concept and raised this question of whether a state that has not ratified can submit a claim with their

Legal Affairs Branch, which in turn consulted the Canadian Embassy to the UN.

Part of their reply is quoted here:

“We examined whether the terms “Coastal States” used in UNCLOS could include States that are not parties to the Convention in the context of

Article 76 and Annex II of UNCLOS (i.e. delimitation of the outer limits of the continental margin). The question of whether the Commission on the

Limits of the Continental Shelf should accept for consideration a submission from a State which is not a party to the Convention was raised at the Eighth Meeting of the States Parties to UNCLOS, held in 1998.

Delegations felt that the Meeting did not have the competence to provide a legal interpretation and added that the Commission should request the

Legal Counsel for an opinion only when the problem actually arises.

UNCLOS does differentiate between “State Parties” to the Convention and

“Coastal States” (for example, Annex II provides that members of the

Commission are elected by “States Parties” and then refers to the

15/04/20 17 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

“Coastal State” making a submission to the Commission). Therefore, we believe the door is not closed for Canada to make a submission before ratifying UNCLOS, although there is always the possibility that the

Commission could rul e our submission inadmissible.” (Restricted letter is source, not sure how to reference it)

The author’s analysis is that DFAIT are ready to argue that Canada can make a partial submission to the Commission and will take the necessary steps through diplomatic channels to smooth its passage.

6.3 Initial and subsequent partial claims and precedents set

In very general terms, international law is made up of two types of components, a

Convention or treaty, which is binding only on parties to it, and customary

International law which is generally binding on all states. The two are sometimes interrelated as they are in UNCLOS which “combined codification of existing rules of customary International law with progressive development of the law.”

(Russell, 1994). Both rely on precedence, the referring back to previous practices and decisions by courts, and the concept that precedents are vital to future actions is enshrined in both.

The CLCS is a creation of a Convention, and is bound by all the Convention, in particular Article 76 and Annex ll. Article 76 contains some “codification of existing rules of customary International law” and some new law. Furthermore, the CLCS has created some rules of its own, (the Guidelines, Rules of Procedure and Modus Operandi) and these together with Article 76 have yet to be tested under the harsh light of reality against an actual submission. The first submission, then, will be seen as a test of Article 76, of the authority of the

CLCS, its literature and how it intends to operate, of the possible interpretations of the Convention, and of the possible interventions of the States Parties.

Because the concept of precedent is inherent in International law, the results of all these will be seen as establishing precedents for all future submissions. The first submission will give power to first state.

Consequently, all wide margin states will pay the strictest attention to the first submission. Depending on how it is interpreted, those with submissions under development may have to modify their approach. Coastal States who have not commenced preparation of a submission will be guided by not only the

Convention, the Guidelines, Rules of Procedure and Modus Operandi, but by the precedent established in the way the first submission was addressed. A wide margin state wishing to submit a claim will therefor consider very carefully whether it wishes to submit first or not.

15/04/20 18 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

6.4 Timing Considerations

Sections 4 and 5 discussed the advantages of preparing a Partial Claim and the advantages of submitting a partial claim. The two have different time scales.

Section 6.3 introduced the issues surrounding the order of submitting, (ie to be first or not).

Annex ll of UNCLOS establishes the time scale for submissions where it rules that a Coastal State that intends to claim a continental shelf must do so “within

10 years of the entry into force of this Convention for that State.” Since the

Convention entered into force in 1994, the 60 States who ratified before 1994 have until 2004 to make a claim and another 73 will be spread over the period to

2010. There is speculation that the States Parties will agree to start the ten years from the time that the final Guidelines were issued, 1999, on the grounds that early ratifiers are at a disadvantage since the rules of the game were not established until then. Indeed, there is a precedent for this when the Third

Meeting of States Parties decided that should any of the 60 original ratifying

States be affected adversely as a consequence of the delay of two years in the date of the election of the CLCS, States Parties would review the situation.

Potential claimants counting on such a reprieve may be one reason there have been no claims submitted to date.

Another factor in the time scale for submitting is the membership of the CLCS.

The current (and first) Commission was elected in March, 1997, for a term of five years. Even though members can seek re-election in 2002, they will find the competition much stronger than in the first round since many more states will have ratified and be eligible to nominate candidates. There appears to be two general approaches discussed among margineers concerning the present

Commission. One is that the first Commission has done its job, which was to prepare and publish the Guidelines; they may now gracefully retire and members who have no ego involvement in the Guidelines will judge submissions made to the next Commission. The countervailing viewpoint comes from States who believe that the current membership will look favorably on their claim, and those

Coastal States want to submit before the next Commission is elected. There is thus one camp that is anxious to submit before March 2002, and another that has no intention of submitting before that date.

It is instructive to examine where other wide margin states are in their preparations. It is also very speculative. The last two years have produced a number of false rumors that one state or another was ready to submit, yet none have. Consequently the following should be read with a great deal of caution.

National representatives have made the following statements in public meetings.

Australia has completed surveys around national territory and expects to finish analysis and interpretation by end 2001. Ireland has completed initial data acquisition, expects to complete data analysis by summer 2001 and hopes to be finished by the end of 2001. New Zealand anticipates no problem in presenting

15/04/20 19 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM submission by their 2006 deadline. Norway began collecting new data in 1996 and will be ready for 2006 deadline. Russia has a target date of end 2001, even though their “ten year” date is 2007. France is doing a lot of surveying in the

Western Pacific, but being quiet about their submission plans. (I know of no others who are close and would appreciate any information.) Aside from these few, no one else has made public statements about being prepared: many have said that they are not prepared and are seeking help.

Why is this timing important to Canada? We have not ratified yet, and our tenyear period will not begin until we do. If we are interested only in the preparation of our own claim, then timing is not yet an issue. If, on the other hand, Canada wishes to benefit from the advantages outlined in Sections 4, 5 and 6.3, timing becomes critical. Time is of the essence if we are to maximize the advantages of being first to submit.

6.5 Risk Analysis

Assessing the risks associated submitting a Partial Claim is best done by considering the possible outcomes that could arise from such an action. Risk is considered by balancing what has been invested against what could be gained or lost. a. CLCS will not consider claim

The CLCS might refuse to consider the claim, on the grounds that Canada has not ratified or that Partial Claims are not acceptable. Whether or not the CLCS has the authority to refuse is beyond the scope of this paper and will be addressed by DFAIT through diplomatic channels in their preparations. As a worst case, suppose the Commission refused and was supported in their refusal by States Parties. The effort in preparing the Partial Claim will not have been lost because of the benefits discussed in Section 4, and because the material will be used later when the complete claim is prepared. What else would have been lost will depend on how the actions of the Commission are viewed by other Coastal

States. The Commission might be viewed as the champion of all that is right and just in the world, or they might be viewed as narrow-minded obstructionists drunk with their own power who do not really understand how international law really works. Which of these extremes, or a more likely intermediate position between them, is really the concern of DFAIT. It will be worth making a Partial Claim even if the Commission rejects or attempts to reject it. b. The claim will be examined and found to be deficient

If the Commission is reluctant to accept a Canadian Partial Claim, yet is fearful of rejecting it outright, they may commence an examination then find that it is deficient in some way so they have grounds to send it back. The guidelines and modus operandi list include requirements to provide extensive documentation, and statements that the CLCS will examine it for completeness before

15/04/20 20 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM proceeding to examine the contents. A claim that the CLCS does not think meets their standard for contents or format could in theory be rejected by them without any recommendations being made. As preparers of a claim, we could anticipate this in one of two ways: ensure that the Canadian claim meets the letter of the

Convention, guidelines, and modus operandi, or choose not to meet them in certain known areas and be prepared to argue for the differences. In the first case, the risk is simply that the Commission will try to find some way to interpret its own words in such a way as to reject the claim, a path they will not enter into lightly. The second case risks the entire claim becoming bogged down in a dispute over a minor point and not getting the recommend it needs. The cases will have to be carefully weighed. c. Claim will later be found to be smaller than could have been claimed

The Partial Claim could be examined and a recommendation as to its acceptance made by the CLCS, but the area could later be found to be smaller than could have been claimed. This risk is also present with complete claims. Unless a claim is based on an exhaustive data set, it runs the risk that later collection of data will change the location of lines within it. It must be noted that new data are as likely to move a claimed line further landward as move it seaward. A Partial Claim in fact risks losing less of the maximum territory it might have claimed since the

Partial Claim will encompass at most ten percent of the complete claim.

7. Approaches to preparing a Partial Claim

A classified document to the Federal Cabinet in 1995 (many of the points raised are included in Macnab,1994) suggested there were three approaches to preparing a complete claim:

“(1) No further surveying, which would cost nothing, but might jeopardize Canada’s ability to influence the resolution of resource and environmental issues beyond 200 nautical miles.

(2) A moderate program of additional data collection in areas of the margin deemed to be of high priority because of known resources at or beneath the seafloor.

(3) A vigorous program of data collection to maximize the limits to our continental margin along the entire length of our coastline beyond all reasonable doubt.’ Ref

Preparing a Partial Claim will allow some theoretical comparing of the results from each of the three approaches and an assessment of the gains that can be excepted with increased amount of data. It is possible to simulate these approaches through selecting different subsets of the existing data. This does not preclude the possibility that the project may lead to some data collection.

Following iterative model of Monahan et al 1999, the most economical and simplest method is to begin with the “no further surveying” approach (1) as the

15/04/20 21 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM first iteration and use existing data to prepare a claim. This claim would then be analyzed critically within Canada and a decision made whether it appeared likely to meet our objectives if it were submitted. Canada could then decide to submit it and if the claim were accepted as submitted, there would be no need for additional data collection in that area. We would gain the advantages addressed above. On the other hand, should the first iteration Partial Claim not be considered strong enough, or should the CLCS reject the claim, we could initiate

Approach (2), a moderate program of additional data collection, to strengthen any weaknesses in the claim. If the second iteration proved effective, we would have gained a lot more knowledge and benefits from only a modest investment.

Should this not be the case, then the third iteration would have to consist of a vigorous program of data collection (approach 3). These steps are summarized in Table 2 below.

1 Scenario One - No further surveying,

1.1 Select an area for which a claim could be prepared by mid 2001.

1.2 Assemble / access existing data

1.3 Analyze data and prepare claim

1.4 Prepare supporting material as required by the CLCS Guidelines.

1.5 Submit claim through diplomatic channels

1.6 Defend claim to Commission

1.7 Publicize successful result OR go to Scenario Two, Step 2.3

2 Scenario Two moderate program of additional data collection

2.1 Select an area for which a claim could be prepared by late 2002.

2.2 Assemble / access existing data

2.3 Prepare a plan to collect the necessary data.

2.4 Acquire funding.

2.5 At sea data collection

2.6 Analyze data and prepare claim

2.7 Prepare supporting material as required by the CLCS Guidelines.

2.8 Submit claim through diplomatic channels

2.9 Defend claim to Commission

2.10 Publicize successful result OR go to Scenario Three, Step3.3

3 Scenario Two vigorous program of additional data collection

3.1 Select an area for which a claim could be prepared by late 2003

3.2 Assemble / access existing data

3.3 Prepare a plan to collect the necessary data.

3.4 Acquire funding.

3.5 At sea data collection

3.6 Analyze data and prepare claim

3.7 Prepare supporting material as required by the CLCS Guidelines.

3.8 Submit claim through diplomatic channels

3.9 Defend claim to Commission

3.10 Publicize successful result

Table 2 Summary of steps in scenarios of increasing levels of complexity from no data collection to considerable data collection

15/04/20 22 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

8. Selection of geographic area to be claimed

Canada does not lack areas that will eventually be claimed under Article 76, and any sub-section or smaller area chosen for a Partial Claim has the potential to yield advantages to Canada as an exporter of goods and services and in diplomatic / legal circles. However, there are a number of imperatives that must be met by any candidate area, as elaborated in Section 8.1. Once these are met, choosing a part of the margin that is an optimal candidate for a partial claim will be governed by a number of practical considerations, as discussed in Section

8.2.

8.1 Imperative characteristics of area selected

1. Must fall within the ambit of the CLCS.

This may seem obvious, but the CLCS may seek any escape clause that would permit it to not consider a partial claim. To ensure that the CLCS cannot so act, the Partial Claim area must be one that does not include a bilateral boundary extension.

2. Must be covered by an appropriate amount of data.

Depending on which Scenario is adopted, the area must have sufficient data already or must be easily accessible by research platforms to collect more data.

3. Must test the Guidelines in a credible fashion.

The first claim could be one that includes all the intricacies of Article 76 or it could be an example of the simplest case. Continental Margins vary considerably and the case for each will have to be built up accordingly. The simplest case would be one where the Continental Slope was a fairly straight, single surface, the Foot of the Slope was well defined, 350 nautical miles constraint was used, and the

Formula line was the Foot of the Slope + 60 nautical miles. Such a case would need only bathymetric data to Foot of the Slope depth, baselines and some distance measurements. At the other end of the spectrum would be a case where the Continental Slope consisted of multiple surfaces, isolated elevations, including a ridge, where the Foot of the Slope was nowhere to be found requiring

Evidence to the Contrary to be invoked, where the 2500 m contour plus 100 nautical miles Constraint was used and where the Formula line was the sediment thickness line. In this case, a complete hydrographic, geologic and geophysical mapping of the margin to considerable depth would be required. Most cases will fall between these extremes, of course.

Table 3 presents one scheme for classifying the degrees of complexity for the differing combinations of circumstances possible. An area to be claimed is classified with a five digit code, with the simplest being 1.1.1.1.1 and the most complex 3.2.3.3.2. With 108 combinations, it is impossible to have a strict

15/04/20 23 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM hierarchy of difficulty, but generally the higher the number, the more complex the claim is.

Feature Characteristics Code

Continental Slope single surface

multiple surfaces, isolated elevations

includes ridge

1

2

3

Foot of the Slope

Constraint used

Formula line used

Evidence to the contrary well defined

poorly defined

350 nautical miles

2500 m contour plus 100 nautical miles

combination

Foot of the Slope + 60 nautical miles

sediment thickness

combination not used

used

1

2

3

1

2

1

2

1

2

3

Table 3. Tentative cheme for assigning numerical coding to complexity of continental slopes over which a claim might be made.

The Guidelines are supposed to include the Commission’s requirements for data to cover the entire range of possibilities. If one were solely seeking to test them, finding an area for the Partial Claim that encompassed the most difficult and complicated case, i.e. a 3.2.3.3.2, would be one way of doing so. That claim would be labor and data –intensive and would take so long to produce that it is unlikely to be the first submitted. A claim that can be prepared in a more reasonable time frame and still test elements of the Guidelines would of necessity deal with a less complicated section of margin, but would nevertheless pro vide a credible test of the CLCS’s words.

4 Must provide the advantages discussed in Section 4.

Section 4 of this paper outlines the advantages to be gained from preparing a

Partial Claim. These advantages will only be realized if an appropriate area is chosen.

5 Must be able to yield a Partial Claim in a form suitable for submission in a short period of time.

The advantages being the first to submit a claim are described in Section 5, while the known preparations that some countries are engaged in are listed in Section

6.4. It is clear that the window of opportunity of being the first to submit will not be open for much longer. A Partial Claim that can be prepared quickly is consequently highly desirable.

8.2 Candidate Areas

Of Canada’s three oceans, the Atlantic is the only one that passes all five imperatives, as summarized in Table 4. The Arctic is simply not well known, difficult to access, and complicated by the presence of two distinct Ridges, and

15/04/20 24 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM preparing any type of claim there will take years. (Haworth et al, 1995). It is unclear whether there will ever be a claim in the Pacific; if there is, it will probably be based on exceptions (the so-called Bay of Bengal clause) and will be controversial. The candidate area must therefor come from the Atlantic. There is enough data covering most of the Atlantic margin to permit using Scenario One of Section 7, “No further surveying”. It remains to be tested whether this will produce a claim suitable for submitting, or whether iterations to Scenario Two or

Three will be required.

Musts Atlantic Arctic Pacific Remarks

Must fall within the ambit of the CLCS.

The area “at risk” must be acceptable

Must be able to yield a Claim in a short period of time.

Must be covered by an appropriate amount of data.

Must test the Guidelines in a credible fashion.

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO NO GO NO GO

Provided no bilateral dispute

Controllable

GO NO GO NO GO To be tested

GO GO GO

Table 4. Analysis of Canada’s three oceans suitability for a Partial Claim.

8.3 Comparison of areas

The Atlantic margin can roughly be divided into the Scotian Margin, Grand

Banks, Flemish Cap, and Southern and Northern Labrador Margins. Each of these must be meet the same “Musts” as the three margins were tested against in Section 8.2. This is tabulated in Table 5. Sub-sections that do not lie close to a bilateral boundary can be established within all but the Northern Labrador

Margin, which is close enough to Greenland to require consideration of a boundary with Denmark, and therefor does not fall within the ambit of the CLCS, and cannot be used. The ‘isolated elevation’ of Orphan Knoll on the Labrador

Margin may conflict with Paragraph 4.4.2 of the Guidelines which states in part

“... when isobaths are complex or repeated in multiples, the selection of points along the 2,500 m isobath becomes difficult...Unless there is evidence to the contrary, the Commission may recommend the use of the first 2,500 m isobath from the baselines...”. Canada would want to use the contour on the outer edge of Or phan Knoll to maximize our claim and this would not be the “first contour” referred to in Paragraph 4.4.2. Allowing the possibility for the Commission to require justification for yet another case of “evidence to the contrary”, or indeed acknowledging that they have the right to insert such a requirement, militates against using the Southern Labrador Margin section for the Partial Claim. Within the southern three zones, the ‘area at risk’ can be controlled to an acceptable level. The three sections seem to be covered by approximately the same amounts of data. They also appear to test the Guidelines to a similar degree.

Consequently, deciding between them must be done at a more detailed level.

15/04/20 25 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

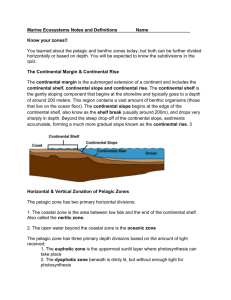

Figure !. Candidate areas for Partial Claim in Atlantic.

Red line is 200 nautical miles. Thin black line is 2500 m depth contour. Thin blue line is predicted limit of Continental Shelf.

Musts Scotian Grand Flemish Southern Northern

Margin Banks Cap Labrador Labrador

Must fall within the ambit of the CLCS.

The area “at risk” must be acceptable

Must be able to yield a Claim in a short period of time.

Must be covered by an appropriate amount of data.

Must test the Guidelines in a credible fashion.

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

NO GO

GO

NO GO

GO

NO GO

GO

GO

GO

GO

Table 5.

Analysis of areas within the Atlantic Margin for suitability for a Partial Claim

The real crux of any extended claim lies in being able to delineate the Foot of the

Slope, or in proving that it cannot be found and therefor that evidence to the contrary must be invoked. Preliminary attempts at mapping this feature in Atlantic

Canada (Somers, 1994, Gray, 1994, as reported in Monahan and Macnab, 1995,

Fig 23.) based on profiles constructed from contour maps differ from each other by up to tens of nautical miles. The producers of the early estimates of Foot of

15/04/20 26 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM the Slope location do not appear to have considered the ‘evidence to the contrary’ clause and drew a continuous line everywhere; it is always possible that

Foot of the Slope does not exist in this area. if there are any differences in finding the Foot of the Slope between the three possible areas, these may be that the

Scotian Margin is smooth and may not have a morphological break, Grand Banks is heavily incised with canyons and will therefore include many local breaks that could be considered, while Flemish Cap profiles show several breaks before abruptly terminating on the virtually flat abyssal plain. There is no clear advantage in choosing any of these sites.

Based on the preliminary attempts to locate the Foot of the Slope, it appears that on the Scotian Margin, the Foot of the Slope lies inside 200 nautical miles, although Sommers 1994 “zone of uncertainty” extends well beyond 200 nautical miles. Nevertheless, it appears that establishing a claim beyond 200 nautical miles will require the use of the sediment thickness formula (Monahan and

Macnab, 1995, Fig 23). For the Grand Banks and Flemish Cap sites, Foot of the

Slope will be no easier to find, although Foot of the Slope + 60 nautical miles appears to coincide with the outer constraint, so that sediment thickness will not be needed.

The outer constraint for the Scotian Margin will be the 350 nautical miles line, while the other two areas will require use of the 2500 m depth contour.

To summarize, Table 6, the Scotian Margin will probably need sediment thickness determination, the other two will not. On the other factors, the three areas seem to be about the same.

Steps in preparing a claim Scotian Shelf Grand Banks Flemish Cap

ESTABLISH THE ZONE POSSIBLE

DRAW 350nm LINE

DRAW 2500m + 100nm LINE straightforward smooth contour

DRAW OUTER CONSTRAINT LINE

IS 2500m CONTOUR NEEDED?

350 nautical miles no

DEFINE BASIS FOR GOING BEYOND 200

NAUTICAL MILES

MAP ‘FOOT OF THE SLOPE’ unknown difficulty

IS EVIDENCE TO THE CONTRARY NEEDED? not examined

PREPARE OPTIONS BEYOND 200

NAUTICAL MILES

DRAW ‘FOOT OF THE SLOPE’ + 60nm straightforward straightforward convoluted contour straightforward convoluted contour

2500m plus 100 nm 2500m plus 100 nm yes unknown difficulty not examined

SEAWARDS OF OUTER CONSTRAINT LINE? no

IF YES, END OR GO TO NEXT ITERATION

IF NO,DRAW SEDIMENT THICKNESS LINE needed

SEISMIC DATA

DRAW OUTER LIMIT straightforward yes not needed scant not needed distance and/or thickness coincides with constraint yes unknown difficulty not examined straightforward yes not needed not needed coincides with constraint

Table 6. Evaluation of condidate areas against steps in preparing a claim.

The candidate areas can be further compared using the degree to which they satisfy the benefits outlined in Section 4. These can be considered as “wants” in

15/04/20 27 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM a conventional decision analysis setting and assigned numerical values as in

Table 7.

Considering the first benefit, “Allows deeper analysis of the Guidelines”, the term deeper can be interpreted to mean that the more complicated the claim, the more the Guidelines are exercised. Complication can be assessed using the hierarchy of Table 3 Section 8.1, under which the Scotian Margin rates 1.2.1.2.1, the Grand

Banks would rate 1.2.2.1.1, and Flemish Cap 2.1.2.1.1, which are all very close on this scale. Considering Possible Outcomes (Section 4.1.1), it would seem that

Scotian Margin, which alone will require the use of sediment thickness, is more likely to satisfy outcome a) Unearthing of weakness or contradictions in the

Guidelines. The other outcomes score about equally for the three areas.

Assessing the second benefit, “Permits testing, analysis and verification of existing mapping capabilities and data sets” depends on the availability of different data sets. Only the Scotian Margin has been surveyed by MBES, and consequently it must rate higher than the other two. Hughes Clarke, 2000,

(actually written in 1998 before the Guidelines were released) has reviewed possible use of MBES for Law of the Sea determinations and, after pointing out the advantages of this type of data, concludes “Unfortunately, such data are only rarely available....”. The Scotian Margin data set is indeed rare, and will be one of the first to be examined for Article 76 purposes.

Maximizing the returns from “Allows testing, analysis and verification of accuracy and completeness of data sets”, the third benefit, is clearly dependent on the types of data available. Although the same bathymetric database exists for all three areas, only the Scotian Margin is covered by the new MBES data. This gives a strong edge to this area, although each of them will produce considerable benefits.

“Enabling CARIS LOTS testing with real data” is best performed with the largest amount of data at the largest scale. For ocean data, this is MBES, and again the

Scotian Margin has a lead over the others. In fact, it is doubtful that CARIS LOTS has ever been tested with MBES data.

“Testing, analysis and verification of methodologies for finding (both)Foot of the

Slope and the Gardiner (sediment thickness) line” will be doable only on the

Scotian Margin, since sediment thickness will not be required for the two northern areas.

The development of improved Cost estimates for preparing a Complete Claim can be done for any area, but will benefit the most from the Scotian Margin, the only area where MBES data exists. Determining its contribution compared to its cost will greatly help future planning.

Wants (Benefits) Scotian Grand Flemish

15/04/20 28 D Monahan

EARLY AND PARTIAL CLAIM

Allows deeper analysis of the Guidelines

Permits testing, analysis and verification of existing mapping capabilities and data sets

Allows testing, analysis and verification of accuracy and completeness of data sets

Enables CARIS LOTS Testing with real data

Permits testing, analysis and verification of methodologies for finding Foot of the Slope and the sediment thickness line

Permits Cost Comparisons between Complete and Partial Claims

Totals

Margin Banks Cap

10

8

9

10

10

5

10

62

8

5

0

5

6

6

8

38

5

0

5

8

6

6

8

38

Table 7. Weighing the wants/benefits of the candidate areas.

9 Decision Analysis

9.1 Recommendation One: To prepare a Partial Claim or not

The benefits to Canada that might be derived from preparing a Partial Claim are myriad. To begin, the data assembled and the results of the analysis can become a portion of the complete claim should it be decided not to submit this Partial

Claim. This is work that would have to be done at some point even if the Partial