The Importance of Imperviousness William Lord N.C. Cooperative

advertisement

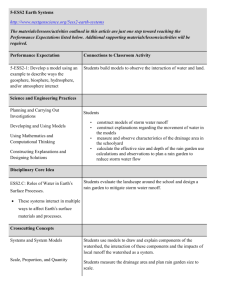

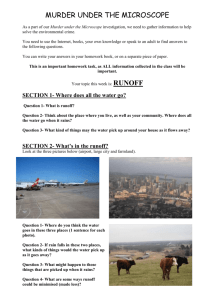

The Importance of Imperviousness William Lord N.C. Cooperative Extension Service As you drive around these days you will notice more impervious areas: roads, buildings, and parking lots with less greenery or vegetated areas. Imperviousness is important because it can affect our drinking water supply as well as flooding during large rain storms. As we remove vegetation like trees, grass, and shrubs and replace them with concrete and asphalt rainwater is unable to soak into the ground via infiltration. Infiltration is important because in natural landscapes rainwater is slowed and spread out by plants and soil so that it can evaporate and recharge moisture in the atmosphere or soak into the ground where it can recharge vital groundwater resources. Groundwater slowing recharges our streams and rivers and provides drinking water for many of our residents who depend on wells. As rainwater soaks into the soil many pollutants are removed from it via filtration and other natural processes. A one inch rain will drop 27,500 gallons of water on an acre of land, and since most areas of North Carolina receive in excess of 40 inches of rainfall per year, a lot of water needs to be processed by the natural water recycling system. But what happens when all of this rain falls on impervious surfaces? If it cannot soak into the ground, rainwater collects in large quantities. As water moves it gains energy and velocity and travels to the lowest point or waterway in the landscape. As this rainwater – now called runoff – travels, it can concentrate and cause damage. Streams that receive urban stormwater runoff are frequently eroded and sometimes create small canyons, becoming what is known as incised streams. Since the natural water cycle has been interrupted by paving over soils and removing vegetation, stormwater runs directly into streams during rain storms creating mini-floods. This is why the National Weather Service issues so many urban flooding advisories in cities during heavy rains. When the rain ends, the streams may dry up since groundwater recharge has been prevented by impervious surfaces. The net result is unstable, unhealthy streams. As rain water travels over impervious surfaces it picks up whatever had been deposited on the pavement or other surface: oil, grease, sediment, or trash. These pollutants are deposited directly into streams. Storm drains on city streets are connected directly to streams, so any pollutant washed off a city street in a rain storm flows directly to our streams and rivers. Sediment is the number one cause of water pollution in North Carolina and the United States, and sediment is washed off disturbed land from construction sites, agricultural fields, or even neglected home landscapes. What can citizens do to protect our streams and rivers from stormwater runoff? Urban development and agriculture are part of our lives and economy and will always be with us. However, we can do things that allow development and agriculture to coexist with clean water. The agricultural community has been installing BMPs – best management practices – to protect water quality for decades. Famers use grassed waterways, conservation tillage, and sediment basins to protect streams from runoff. The urban development community has begun to adopt practices used by the agriculture community and to develop practices unique to the urban landscape to protect water quality. Some of these practices include level spreaders, rain water harvesting, green roofs, stormwater wetlands, permeable pavement, and bioretention beds. Even homeowners can get into the act. One possibility for homeowners to reduce stormwater runoff and flooding is to install a rain garden in their yard. Rain gardens are shallow bowls dug into the ground where they can intercept stormwater runoff from gutters and downspouts or paved driveways. The bowl is dug large enough to collect the runoff from a one inch rain storm. The rain garden should be mulched with hardwood bark (it will not float away) and planted with wet-tolerant plants like Virginia Sweetspire, black-eyed susan, red bud, inkberry, or joe-pye weed. After a rainfall event the rain garden will fill with water and then slowing infiltrate the water into the ground, lessening downstream flooding and recharging groundwater. Rain gardens are good for the environment and can be an interesting and attractive addition to the home landscape. For more information on rain gardens see: http://www.bae.ncsu.edu/topic/raingarden/ for N.C. State University’s backyard rain garden program. A rain garden instaled at Lake Royale to protect the lake from parking lot runoff