HEAD INJURY - Traumatic Brain Injury Survival Guide

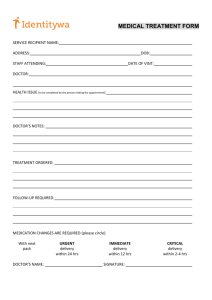

advertisement