Chapter 2 : Multiplicative Cipher

advertisement

Chapter 2 – Multiplicative Cipher

In this chapter we will study the Multiplicative Cipher. Instead of adding a number as we did in

the Caesar Cipher, we will now multiply each plain letter by an integer a, our secret encoding

key. As some of them fail to produce a unique encryption, we will discover an easy criterion for

keys that produce the desired unique encryptions (the “good” keys) and apply it to different

alphabet lengths. When doing so we will discover very important mathematical encryption tools

such as Euler’s -function, Euler’s and Lagrange’s Theorem and study further examples of

groups, rings and fields.

2.1 Encryption using the Multiplication Cipher

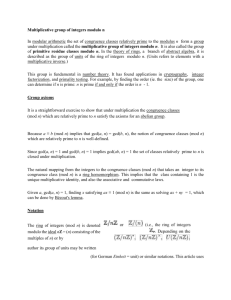

Instead of encoding by adding a constant number, we multiply each plain letter by our secret key

a. Since each plain letter turns into 0 for a=0 and remains unchanged for a=1, we start with a=2.

We will multiply MOD 26 as we are using the 26 letters of the English alphabet. We get the

following encoding and decoding table.

PLAIN LETTER:

Secret key: a=2

Cipher letter:

A

0

B

1

C

2

D

3

E

4

0

2

4

6

8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24

a

c

e

g

i

F G

5 6

k m

H

7

I

8

o

q

J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

s

u

w

y

0

2

4

6

a

c

e

g

8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24

i

k m

o

q

s

u

w

y

Notice, that only every other cipher letter appears, and that exactly twice. This is not a useful

encryption system since it may yield ambiguous messages. As an example, let’s encode and

decode NAT and ANT.

PLAIN LETTER

Secret key a=2

N

13

A

0

T

19

A

0

N

13

T

19

Cipher letter

0

a

0

a

12

m

0

a

0

a

12

m

You can see the dilemma of this message. Decoding “aam” can either yield NAT or ANT as the

plain text. What would you do? Of course, you don’t want to receive any more ambiguous

messages. Let’s simply test all possible keys of the multiplication ciphers MOD 26:

PLAIN LETTER

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Encoding

Key a

a

0

A

0

B

0

C

0

D

0

E

0

F G

0 0

H

0

I

0

J

0

1

0

1

2

3

4

5

7

8

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

2

0

2

4

6

8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24

3

0

3

6

9 12 15 18 21 24

4

0

4

8 12 16 20 24

5

0

5 10 15 20 25

6

0

6 12 18 24

4 10 16 22

7

0

7 14 21

2

9 16 23

8

0

8 16 24

6 14 22

9

0

6

4

2

1

K

0

4

L M

0 0

2

3

3 12 21

9 18

1 10 19

2 11 20

10

0 10 20

4 14 24

8 18

11

0 11 22

7 18

12

0 12 24 10 22

13

0 13

0 13

0 13

0 13

0 13

14

0 14

2 16

4 18

6 20

8 22 10 24 12

15

0 15

4 19

8 23 12

16

0 16

6 22 12

2 18

17

0 17

8 25 16

7 24 15

18

0 18 10

2 20 12

19

0 19 12

5 24 17 10

8

3 14 25 10 21

8 20

6 18

1 16

4 16

5 20

8 24 14

4 22 14

2 22 16 10

8

4

6

0 13

2 16

2 17

0 22 18 14 10

23

0 23 20 17 14 11

24

0 24 22 20 18 16 14 12 10

25

0 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10

6

2 24 20 16 12

8

5

8

4

6

4

2

4

6 10 14 18 22

1

6 11 16 21

2

8 14 20

3 10 17 24

5 12 19

4 12 20

8 18

2 10 18

7 16 25

2 12 22

1 12 23

8 17

6 16

8 19

4 15

6 18

4 16

2 14

0 13

0 13

0 13

6 20

8 22 10 24 12

3 18

7 22 11

8 24 14

4 20 10

3 20 11

2 19 10

1 18

4 22 14

4 23 16

2 22 16 10

3 24 19 14

7

Z

0

2 18

0 22 18 14 10

2 25 22 19 16 13 10

8

8

Y

0

0 13

2 20 12

22

8

X

0

8 20

4 18

6 25 18 11

0 20 14

2

6 21 10 25 14

4 21 12

V W

0 0

8 11 14 17 20 23

6 15 24

5 16

6 22 12

0 20 14

2 23 18 13

5

6 14 22

0 13

0 21 16 11

7

6

9 20

U

0

4 10 16 22

4 14 24

20

1 22 17 12

2

8 15 22

5 14 23

0 18 10

1 20 13

4 24 18 12

1

8 16 24

0 16

T

0

7 12 17 22

6 12 18 24

0 14

S

0

8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24

0 12 24 10 22

5 22 13

8

2

21

6

R

0

8 12 16 20 24

0 10 20

9 24 13

6 24 16

3 22 15

0

0 13

4 20 10

6 23 14

0

2 13 24

2 14

0 13

4

4 13 22

6 16

6 17

0

6 13 20

2 10 18

2 12 22

2

8 13 18 23

8 14 20

4 11 18 25

4 12 20

0

P Q

0 0

7 10 13 16 19 22 25

6 10 14 18 22

9 14 19 24

N O

0 0

6

9

9

8

2 21 14

7

4 24 18 12

6

4 25 20 15 10

5

2 24 20 16 12

1 24 21 18 15 12

0 24 22 20 18 16 14 12 10

9

8

7

9

6 24 16

6

5

8

4

3

9

6

8

6

4

2

4

3

2

1

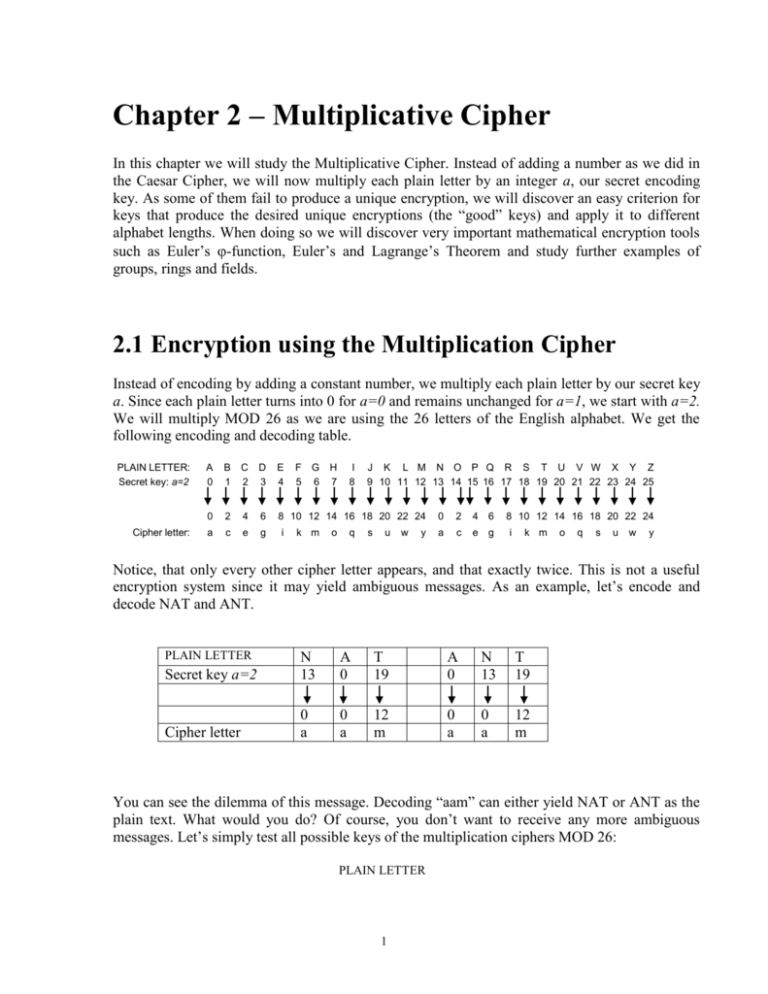

We learned already that the key a=2 (as can be seen in the 3rd row) does not produce a unique

encryption. So which ones do? Each row that contains each integer from 0 to 25 exactly once and

therefore yields a unique cipher letter will serve. Simply by looking at the table, we find that the

following keys (whose rows are bold) produce a unique encryption and therefore call them the

good keys:

a = 1,3,5,7,9,11,15,17,19,21,23,25

Why those and what do they have in common? They seem to not follow any apparent pattern.

Are they the odd numbers between 1 and 25? No, 13 is missing. Or are they possibly the primes

between 1 and 25? No, 9,15, 21 and 25 are not prime and the prime 13 is missing. So, let’s

understand why the bad keys

a = 2,4,6,8,10,12,13,14,16,18,20,22,24

don’t produce a unique encryption. We have to understand why multiplying by a bad key a

MOD 26 yields some integers more than once and others not at all.

An extreme example would be when a=0: all plain letters are translated into 0’s which are all a’s

so that no decryption is possible.

If a=1 is used as a key, each cipher letter equals its plain letter which shows that it does produce

a unique encryption. However, it yields the original text. This is not very useful.

2

The bad key a=2 yields an ambiguous message as we saw in the introductory example: each A

turns into 0 (=a) since 2*0 = 0 MOD 26 just as each N turns into 0 since 2*13 = 26 = 0 MOD 26.

Also, each B and each M turn into 2 (=c) since 2*1 = 2 MOD 26 and 2*14 = 28 = 2 MOD 26.

When you study the a=2 row precisely, you will see that the original 26 plain letters are

converted into 13 “even” cipher letters (the even cipher letters are those whose numerical

equivalent is an even number.) each occurring exactly twice. This is the reason why a=2 yields

an ambiguous decryption.

If a=4,6,8,…,24, we encounter the same dilemma as for a=2. We can see in the table that an A

will always translate into 0 (=a) since the product of any such key a with 0 (=A) yields 0. N

(=13) translates into a for any even key a aswell because

even keys N

4*13 = 2*(2*13) = 2*0 = 0 MOD 26,

6*13 = 3*(2*13) = 3*0 = 0 MOD 26,

8*13 = 4*(2*13) = 4*0 = 0 MOD 26, etc.

Notice in all three equations that because a=2 turns the 13 (=N) into 0 in 2*13 = 0, all the

multiples of a=2 translate the N into 0 (=a). That means:

Because a=2 is a bad key all the multiples of a must be bad keys aswell.

Consider an alphabet length of M=35: the bad key a=5 (why?) will translate the H (=7) into a

(=0), because 5*7 = 35 = 0 MOD 35. Therefore, all the keys that are multiples of 5 such as

a=10,15,20,25,30 will also translate the H into 0(=a). Similarly, the multiples of a=7 will

translate an F (=5) into an 0 (=a) because 7 does so.

a=13 yields an ambiguous message since each even plain letter is translated into a (=0):

a=13 even letters

13*0 = 0 MOD 26,

13*2 = 0 MOD 26,

13*4 = (13*2) * 2 = 0 * 2 = 0 MOD 26,

13*6 = (13*2) * 3 = 0 * 3 = 0 MOD 26, etc.

Each odd plain letter translates into 13 (=n):

a=13 odd letters

13*1 = 13 MOD 26,

13*3 = 13*2 + 13*1 = 0 + 13 = 13 MOD 26,

13*5 = 13*4 + 13*1 = 0 + 13 = 13 MOD 26,

13*7 = 13*6 + 13*1 = 0 + 13 = 13 MOD 26, etc.

Moreover, since a=13 is a bad key its multiples 26, 39, … must also be bad keys. However, we

don’t need to consider keys that are greater than 26 since each of them has an equivalent key less

than 26 that yields the same encryption: the even multiples of 13 (i.e. 26, 52, 78, ...) have its

equivalent key in a=0, a very bad key, since 26=52=78=0 MOD 26. The odd multiples of 13 (i.e.

39, 65, 91, …) have its equivalent key in a=13, another bad key, since 39=65=91=13 MOD 26.

3

Let’s summarize our discoveries. Which keys now yield a unique encryption?

A key a does not produce a unique encryption,

if 1) a divides 26 evenly

or if 2) a is a multiple of such divisors.

We can combine these two criteria into one easy criterion. Can you? Try it!

CRITERION FOR GOOD KEYS

A key a produces a unique encryption,

if the greatest common divisor of 26 and a equals 1,

which we write as: gcd(26, a)=1

Convince yourself that 26 has a greatest common divisor equal to 1 with each of these good

keys a = 1,3,5,7,9,11,15,17,19,21,23,25. Except for 2 and 13, all prime numbers less than 26 are

among the keys (why do they have to?). However, there are some additional integers that are not

prime (i.e. 9,15,21 and 25). That are those that don’t have a common divisor with 26. Thus,

being prime is not quite the reason for a good key, but almost. We, therefore, name the good

keys as follows:

Definition of numbers that are relative prime:

Two integers are called relative prime if their greatest common divisor equals 1.

Examples are: 4 and 5 are relatively prime because gcd(4,5)=1. So are 2 and 3, 2 and 5, 3 and

10, 26 and 27, 45 and 16.

Counter examples are: 45 and 18 are not relative prime since gcd(45,18)=9 and not 1.

343 and 14 are not relative prime since gcd(343,14)=7.

From now on we will use a handy

Notation for the set of possible and good keys:

1) All the possible keys for an alphabet length of 26 are clearly all the numbers between

1 and 26, denoted as Z26. Simply: Z26 = {0,1,2,3,…, 24,25}.

Generally: An alphabet of length M has the keys: ZM = {0,1,2,3,…, M-2,M-1}

2) Now, the good keys are the ones that are relative prime to 26 as listed above and are

denoted as Z26*. Simply: Z26* = {1,3,5,7,9,11,15,17,19,21,23,25}.

Generally: The good keys are those a’s that are relative prime to M and are denoted as

ZM*. (I can not list those here as they depend on the alphabet length M.)

We are now able to summarize how to encrypt a message using the multiplication cipher:

To encrypt a plain letter P to the cipher letter C using the

Multiplication Cipher, we use the encryption function: f : P

C=(a*P) MOD 26. If a is a “good” key, that is if a is relatively prime

4

to 26, then f produces a one-to-one relationship between plain and

cipher letters, which therefore permits a unique encryption.

Among the 12 good keys we pick a=5 to encode the virus carrier message as follows:

PLAIN TEXT

Cipher text

A

0

N

13

T

19

I

8

S

18

T

19

H

7

E

4

C

2

A

0

R

17

R

17

I

8

E

4

R

17

0

a

13

n

17

14

o

12

m

17

r

9

j

20

u

10

k

0

a

7

h

7

h

14

o

20

u

7

h

r

Exercise1: Encrypt the same plain text using the key a=7.

2.2 Decryption of the Multiplication Cipher

Now that the virus carrier message was encoded in a unique manner how can it be decoded? First

of all, you need to know which one of the 12 good keys was used. In some secret manner, the

sender and the recipient had to agree on the encoding key a. Say a=5 was chosen. Now, how do

you decrypt the above message? To do so, we have to look at the encryption equation C=a*P

MOD 26 and solve it for the desired plain text letter P.

In order to solve an equation like 23=5*P for P using the rational numbers, we would divide by 5

or multiply by 1/5 to obtain the real solution P=23/5. However, when using MOD arithmetic and

solving 23=5*P MOD 26, we don’t deal with fractions but only integers. Thus, dividing is

performed slightly different: instead of dividing by 5 or multiplying by 1/5, we first write 5-1

(instead of 1/5) where 5-1 now equals an integer and multiply both sides by that integer 5 -1. We

denote 5-1 “the inverse of 5”. Just as 5*1/5 yields 1, 5 * 5-1 shall equal 1 MOD 26.

Definition of an inverse number:

A number a-1 that yields 1 when multiplied by a is called the inverse of a.

Mathematically: a-1 * a = a * a-1 = 1.

Example1: When using fractions,

5-1=1/5 is the inverse number to 5,

3-1=1/3 is the inverse number to 3,

3/2 is the inverse number to 2/3.

Now, let’s look at examples for MOD arithmetic:

Example2: The inverse of a=3 is a-1 = 2 MOD 5 because a * a-1 = 3*2 = 6 = 1 MOD 5. I found

a-1 = 2 by simply testing the integers in Z5*={1,2,3,4}.

a=4 is inverse to itself modulo 5 since a * a-1 = 4 * 4 = 16 = 1 MOD 5.

5

Example3: Doing arithmetic MOD 7, the inverse of a=3 is a-1 = 5 because a * a-1 = 3*5 = 15 =

1 MOD 7. Again, I found the inverse of a=3 by testing the integers in Z7* ={1,2,3,4,5,6}

The inverse of a=4 is 2 since a * a-1 = 4 * 2 = 8 = 1 MOD 7.

a=6 is inverse to itself MOD 7 since a * a-1 = 6 * 6 = 36 = 1 MOD 7.

Example4: What is the inverse of 3 MOD 11? It is a-1=4 since 3*4 = 12 = 1 MOD 11.

Example5: Try it yourself!

What is the inverse of 5 MOD 11?

What is the inverse of 7 MOD 11?

Back to the virus carrier message. It was encoded MOD 26. Since we calculate MOD 26, thus

dealing with integers from 0 to 25, we now have to find an integer a-1 among those integers that

yields 1 MOD 26 when multiplied by 5: a-1 * 5 = 1 MOD 26. Equivalently stated: what product

of a-1 and 5 equals 1 more than a multiple of 26 such as 27, 53, 79, 105, etc? Aha, there is 105 =

21*5 so that 21*5 = 1 MOD 26. Equivalently stated, 105 divided by 26 leaves a remainder of 1.

Wonderful, that is all we need to solve our encryption function C= a*P MOD 26 for the plain

letter P in order to then decode the encrypted message:

Multiplying both sides of our encryption equation the equation yields

a-1*C = a-1*(a*P)

= (a-1*a)*P

= 1*P

= P MOD 26

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Remark: Solving this equation required the 4 group properties: the existence of an inverse and the closure in (1), the associative

property in (2), the inverse property in (3) and the unit element property in (4). It thus gives a great example that we are only

guaranteed to solve this equation for numbers that form a group with respect to multiplication MOD 26. We will check in the

Abstract Algebra section at the end of this chapter that the set of good keys MOD 26, Z 26* = {1,3,5,7,9,11,15,17,19,21,23,25},

does form a multiplicative group. We can therefore always find a-1 for a given good key a.

Thus our decoding function P = a-1*C MOD 26 tells us to simply multiply each cipher letter by

the inverse of the encoding key a=5, namely by the decoding key a-1=21 MOD 26 and we can

eventually decode:

Cipher text

PLAIN TEXT

a

0

n

13

r

17

o

14

m

12

r

17

j

9

u

20

k

10

a

0

h

7

h

7

0

13

N

19

T

8

I

18

S

19

T

7

H

4

E

2

C

0

A

17

R

17

R

A

o

14

u

20

8

I

4

E

h

7

17

R

For example, multiplying the cipher letter r=17 by a-1 = 21 decodes the r to T=19 since 21*17 =

357 = 19 MOD 26.

The o =14 decodes to I = 8 since 21*14 = 224 = 8 MOD 26,

the m =12 decodes to S=18 since 21*12 = 252 = 18 MOD 26.

6

How does the j decode to the H, and the u decode to the E? Verify this now!

An easier way to determine the decoding key a-1

Decoding a message turns out to be really easy once we know the decoding key a-1. We just had

to multiply each cipher letter by a-1. So, we are left with determining the decoding key a-1

knowing the original encoding key a. To decode the above virus carrier message we found the

inverse of a=5 through a clever check of the products of a and a-1 that produced one more than

multiples of 26. That was trial and error and might take quite a while. We won’t have to do it that

way again since there is a much more straightforward method. To find the inverse for each good

key a, you just need to look back at the 26 by 26 encryption table.

For instance, to find the inverse of the good key a=5 we have to look at the fifth row which

shows that a-1 equals 21 since the only 1 in this row is in the V- or 21-column (5 * 21 = 1 MOD

26). Moreover, you can see that the plain letter V encrypts to the cipher text letter b (=1) when

using a=5 as the encoding key. Take a moment now to verify the

Rule for finding the decoding key a-1:

1) For a given good key a, find the unique 1 in the a-row,

2) From that 1 go all the way up that column,

3) The letter’s numerical equivalent that you hit on the very top is the inverse of a.

Example: If we use the encoding key a=3, we find that the decoding key a-1 is 9 as the 1 occurs

in the J- or 9-column telling us additionally that the plain letter J (=9) encrypts to the cipher letter

b (=1).

Finding the decoding keys for each good key a in the same manner, we obtain the following key

pairs:

Good Encoding

key a

1

3

5

7

9

11

15

17

19

21

23

25

Its decoding key

a-1

1

9

21

15

3

19

7

23

11

5

17

25

Three important observations:

7

1. All decoding keys a-1 in the right column are among the set of all encoding keys a. In fact,

the sets of the encoding and decoding keys are identical. Coincidence? No, it is not. Just as

the regular multiplication of two integers is commutative (i.e. 3 * 9 = 9 * 3 =27) the MODmultiplication is commutative (3 * 9 = 9 * 3 = 1 MOD 26). You can observe this orderdoesn’t-matter rule in the original 26x26 multiplication table: The diagonal line from the top

left to the bottom right forms a reflection line. I.e. 21 is an inverse to 5 MOD 26, therefore 5

is inverse to 21 and the two 1’s are mirrored over the diagonal line. Therefore, the set of all

encoding keys must equal the set of all decoding keys.

2. If we extract those rows with the good keys a = 1,3,5,7,9,11,15,17,19,21,23,25 and their

corresponding columns, we obtain:

1

3

5

7

9

11

15

17

19

21

23

25

1

1

3

5

7

9

11

15

17

19

21

23

25

3

3

9

15

21

1

7

19

25

5

11

17

23

5

5

15

25

9

19

3

23

7

17

1

11

21

7

7

21

9

23

11

25

1

15

3

17

5

19

9

9

1

19

11

3

21

5

23

15

7

25

17

11

11

7

3

25

21

17

9

5

1

23

19

15

15

15

19

23

1

5

9

17

21

25

3

7

11

17

17

25

7

15

23

5

21

3

11

19

1

9

19

19

5

17

3

15

1

25

11

23

9

21

7

21

21

11

1

17

7

23

3

19

9

25

15

5

23

23

17

11

5

25

19

7

1

21

15

9

3

25

25

23

21

19

17

15

11

9

7

5

3

1

This reduced table shows i.e. that 3 and 9 are inverse to each other because of the

commutative property of the MOD-multiplication (exhibited by the diagonal as a line of

reflection). Now every row contains exactly one 1 revealing that there exists an inverse for

each a which is precisely the reason why those a’s are the good keys. Moreover,

multiplying any two good keys yields again a good key. As an attentive reader, we realize

that the MOD multiplication of the keys is closed (recall the group properties in the previous

chapter). Combining this fact with the fact that each key a possesses a decoding key a-1, the

set of the good keys forms a commutative group with the unit element 1. Does that even

mean that the good keys form a field? That would additionally require that the good keys

form a commutative group with respect to addition. Do they? Try to answer it for yourself. I

will answer it at the end of this chapter in the Abstract Algebra section.

3. The only two keys that are inverse to themselves are 1 and 25, which means that the

encoding key equals its decoding key. Let’s check why: 1*1=1 MOD 26 which explains a =

a-1 = 1 (Big deal!). Now when a=25, we have: 25*25 = 625. Since 625=24*26+1 which

means that 625 leaves a remainder of 1 when divided by 26, we have 625 = 1 MOD 26 and

altogether 25 * 25 = 625 = 1 MOD 26.

These calculations were correct but almost required a calculator. Here is a non-calculator

way to understand why 25 is inverse to itself: Since 25 = -1 MOD 26, it follows 25 * 25 = (1) * (-1) = 1 MOD 26. This shows that when using an encoding key that is one less than the

8

alphabet length M, namely a = M-1, then the decoding key must also equal M-1, a-1 = M-1.

The reason is (M-1) * (M-1) = (-1) * (-1) = 1 MOD M. For example: when using an alphabet

length of M = 27 and an encoding key a=26 then its decoding key is a-1 =26. To verify this:

262 = 676 =1 MOD 27.

Here is the C++ Code for the encryption and decryption of the multiplication cipher:

//Multiplication Cipher using the good key a=5

//Author: Nils Hahnfeld, 9/22/99

#include<conio.h>

#include<iostream.h>

void main()

{

char cl,pl,ans;

int a=5, ainverse=21; //as a-1*a=21*5=105=1 MOD 26

clrscr();

do

{

cout << "Multiplication Cipher: (e)ncode or (d)ecode or (~) to exit:" ;

cin >> ans;

if (ans=='e')

{

cout<< "Enter plain text: "<< endl;

cin >> pl;

while(pl!='~')

{

if ((pl>='a') && (pl<='z'))

cl='a' + (a*(pl -'a'))%26;

else if ((pl>='A') && (pl<='Z'))

cl='A' + (a*(pl -'A'))%26;

else cl=pl;

cout << cl;

cin >> pl;

}

}

else if (ans=='d')

{

cout << "Enter cipher text: " << endl;

cin >> cl;

while(cl!='~')

{

if ((cl>='a') && (cl<='z'))

pl='a' + (ainverse*(cl -'a'))%26;

else if ((cl>='A') && (cl<='Z'))

pl='A' + (ainverse*(cl -'A'))%26;

else pl=cl;

cout << pl;

cin >> cl;

}

9

}

}

while(ans!='~');

}

Programmer’s Remarks:

Can

you

understand

the

code

yourself?

Try

to

understand as much as possible first, then continue

reading.

1) This program both encodes and decodes. Say you

first want to encode the letter c then you have to

enter

e

when

asked.

Then

the

if-condition

if

(ans=='e') is fulfilled so that we enter the encoding

part of the program. You are asked to enter your plain

letter in cin >> pl;

As long as you don’t enter ‘~’

the while-condition while(pl!='~') is fulfilled and

the entered plain letter (=pl) is being encoded.

To do so, I distinguish between upper and lower case

letters since they are encoded slightly different.

Say, the lower case plain letter c is entered, then

the condition if ((pl>='a') && (pl<='z')) is fulfilled

and the encryption is being executed by this one

seemingly weird command cl='a' + (a*(pl -'a'))%26; Let

me explain that to you in detail: First you need to

know that each letter is stored as a number: i.e.

A=65, B=66, C=67, .., Z=100, a=101, b=102, c=103,

…z=125. In fact, any character is stored as a number:

i.e. ~=.., $=.. etc. For now, let’s focus on the lower

case letters.

The plain letter c is stored as 103, however, I want

the c to equal 2 in compliance with our translation

a=0, b=1, c=2, etc. which we used in our virus carrier

example. Therefore, I need to subtract 101 from the

103 to get the desired 2, similarly, I again would

have to subtract 101 from any plain letter b=102 to

get the desired 1. In fact, I always have to subtract

101 from each entered lower case plain letter to get

its corresponding number. By subtracting a (=101) from

the entered plain letter in (pl -'a');. I accomplish

this. Subsequently, that difference is multiplied by

the good key a=5 which I defined as such in int a=5.

You could also define a to be a different good key. If

you choose to do so, don’t forget to also redefine the

corresponding decoding key in int a=5, ainverse=21; .

10

Ok, let’s continue with the encoding part. Since we

are performing MOD 26 arithmetic, we use the MODoperator % that guarantees us the product (a*(pl 'a'))%26; to be between 0 and 25. In our example,

after subtracting 101 from the plain letter c we get

the desired 2 that is now multiplied by a=5 yielding

10. This is just what we wanted except that the answer

10 does not equal the desired cipher letter k on the

computer. Therefore, we just have to add a number in

order to get k=111. Which number would that be? Right,

we have to add 101 to the 10 which we do by adding

a=101 in cl='a' + (a*(pl -'a'))%26. Now the cipher

letter cl equals k and we can end the lower case

encoding.

The encryption of upper case plain letter works

similarly except that I have to subtract A=65 (instead

of a=101 as above) to obtain our desired plain letter

number. Say, we want to encrypt the plain letter C=67.

I first subtract 65 =’A’ and then multiply that

difference by the good key a=5 yielding 10 again. The

MOD 26 calculation leaves the 10 unchanged. Finally, I

have to add the usual 65 = A (why?) to obtain the

desired cipher letter.

How do we deal with non-letters? Well, I leave all the

entered non-letters such as ! or . or ? unchanged so

that you can detect the format of the original message

easier. If we don’t want to give an eavesdropper any

additional information about our secret message, we

would firstly either not use such characters at all or

we would expand our alphabet length and encode them

just like the other plain letters. Secondly, we would

translate every upper case plain letter into a lower

case cipher letter so that we don’t reveal information

about the beginning of a sentence. These are valuable

information for an eavesdropper that help cracking the

message. I leave the translation from an upper case

plain letter to a lower case cipher letter as an easy

exercise for you.

2) Lastly, I want to explain the trick how I manage to

encode not only a letter but a whole word or sentence

if necessary. The statements while(cl!='~') and cout

<< cl; cin >> pl; are in charge of it. The first time

the loop passes the line cout << cl; the translated

plain letter pl that was read in as cin >> pl; before

11

the while loop is output as its cipher letter cl. The

trick is now that if we enter more than one letter all

but the first entered letter are buffered (which means

temporarily stored in the computer’s RAM) until read

in in cin >> pl; inside the while loop. Since any

plain letter fulfills the condition in while(cl!='~')

The loop is reentered and the next cipher letter is

displayed in cout << cl; We can then end this while

loop by entering ~ and then choose to either encode,

decode or exit the program. Try it for yourself.

2.3 Cryptoanalysis - Cracking the Multiplication

Cipher

Just like the Cipher Caesar Cipher, the Multiplication is not secure at all. How could it be

broken? Let’s consider two options:

Option 1: Cracking the cipher code using letter frequencies

If plain letters are replaced by cipher letters the underlying letter frequencies remain unchanged.

I.e. if the letter e (the most frequent letter in the English language) occurs 20 times in the plain

text its replacement letter will appear 20 times in the cipher text. Therefore, an eavesdropper

simply has to count letter frequencies to identify the most frequent cipher letter. Its numerical

equivalent reveals the row and therefore the key a as follows:

PLAIN LETTER

0

Keys a

0

0

A

B

C

D

1

0

1

2

3

2

0

2

4

6

3

0

3

6

9

4

0

4

8 12

5

0

5 10 15

6

0

6 12 18

7

0

7 14 21

0

E

0

0

F G

4

8

12

16

20 25

24

2

4

0

H

0

I

0

J

0

K

9 14 19 24

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

3

12

8 13 18 23

2

7 12 17 22

1

6 11 16 21

8

0

8 16 24

9

0

9 18

10

0 10 20

11

0 11 22

12

0 12 24

13

0 13

14

0 14

2

15

0 15

4

16

0 16

6

17

0 17

8

18

0 18 10

19

0 19 12

0

20

0 20 14

21

0 21 16

22

0 22 18

23

0 23 20

24

0 24 22

25

0 25 24

6

1 10

4 14

7 18

10 22

13 0

16 4

19 8

22 12

25 16

2 20

5 24

8 2

11 6

14 10

17 14 11

20 18

23 22

8

5

2 25 22 19 16 13 10

7

4

1 24 21 18 15 12

9

6

3

After intercepting the cipher text, an eavesdropper simply finds the most frequent letter of this

rather brief message. Longer messages reveal the most the letter e equivalent, however, this is

not necessarily so for our message.

Cipher text

a

0

n

13

r

17

o

14

m

12

r

17

j

9

u

20

k

10

a

0

h

7

h

7

o

14

u

20

h

7

He finds the cipher letter h to be most frequent. However, there is no 7 – the numerical

equivalent of letter h - in the E column. This means that the cipher E does not equal 7. In fact, the

cipher E can only be an even cipher letter as only even numbers appear in the E-column. Thus,

among those numbers that occur twice in the cipher code, 14, 17 and 20, we can eliminate the

odd 17. The 14 as the possible cipher E then tells him to test the keys a=10 and a=23.

Since a=10 is a bad key he checks the good key a=23. He decodes all the other cipher letters by

finding their corresponding number in the 23rd row (see above) and then goes up that column to

find the original plain letter. He obtains:

Cipher text

PLAIN TEXT

a

0

n

13

r

17

o

14

m

12

r

17

j

9

u k

20 10

a

0

h

7

h

7

o

14

u

20

0

13

N

11

L

6

G

7

H

11

L

23

X

2

C

0

A

15

P

15

P

19

T

2

C

A

13

14

O

h

7

15

P

That message does not reveal a virus carrier. Certainly, it might be a double encoded message

that has to be decoded twice, possibly using two different keys or even two different ciphers.

Before considering such encoding techniques, we go ahead and check if the other frequent

number, 20, is the cipher E.

Checking the E column, we can see that the possible two keys are the bad one a=18 and the good

one a=5. Again, we just have to find the cipher numbers in the 5th row and then go up that

column to the very top to find the corresponding plain letter. This yields the correct plain text:

Cipher text a

n

r

o

m r

j u k

a h

h

o

u

h

0 13 17 14 12 17 9 20 10 0 7

7

14 20 7

0

13

N

PLAIN TEXT A

19

T

8

I

18

S

19

T

7 4

H E

2

C

0

A

17

R

17

R

8

I

4

E

17

R

As you can see, detecting the most frequent cipher letter is of enormous help in cryptography.

Here, it reduces the number of possible good keys to two. It is not difficult to find the encoded E

in English documents as every 8th letter on average is an E (about 13%), it is therefore by far the

most frequent letter. Consequently, the longer a cipher text, the easier the cipher E can be

detected. Other frequent letters such as T, A, O and N occurring with about (8%) might be of

further help to crack the cipher text.

I will explain the usage of letter frequency as a very important means to crack cipher codes in the

next chapter. In case you wonder why the discussion of cracking codes is made public; why is it

not kept secret to maintain the security of ciphers? The answer is a simple “No”: Only those

encryption systems that withstand all possible attacks are secure and thus useful. Certainly none

of the cryptosystems we have considered thus far. Remember that the first 3 ciphers are meant to

familiarize you with basic encryption systems. Moreover, we build the mathematical foundation

to understand secure encryption systems such as the RSA encryption.

Option 2: Cracking the cipher code using trial and error

(“brute force”)

Knowing that there are just 12 possible unique encryptions MOD 26, the journalist produces the

corresponding 12 rows in the 26 x 26 multiplication table and cracks the code easily.

Cipher text

A

N

r

R

X

W

E

X

D

Y

M

A

L

L

W

Y

L

a=5

A

N

T

I

S

T

H

E

C

A

R

R

I

E

R

a=7

a=9

a=11

a=15

a=17

A

A

A

A

A

N

N

N

N

N

V

Z

L

P

B

C

Q

G

U

K

Y

K

U

G

Q

V

Z

L

P

B

F

B

P

L

Z

O

I

Q

K

S

U

E

I

S

W

A

A

A

A

A

B

V

D

X

F

B

V

D

X

F

C

Q

G

U

K

O

I

Q

K

S

B

V

D

X

F

a=1

a=3

a

A

n

N

o

O

m

M

r

R

j

J

u

U

k

K

a

A

h

H

h

H

o

O

u

U

h

H

14

a=19

a=21

a=23

a=25

A

A

A

A

N

N

N

N

F

H

D

J

Y

S

E

M

C

I

W

O

F

H

D

J

V

T

X

R

M

W

C

G

G

Y

O

Q

A

A

A

A

Z

J

P

T

Z

J

P

T

Y

S

E

M

M

W

C

G

Z

J

P

T

MS Excel as a simple encryption and decryption tool:

I created the following table in MS Excel with the CHAR and the MOD function:

Cipher

text

a

a-1

3

9

5

21

7

15

9

3

11

19

15

7

17

23

19

11

21

5

23

17

25

25

For

example,

I

a

n

r

0

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

13

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

17

X

T

V

Z

L

P

B

F

H

D

J

created

o m

14

W

I

C

Q

G

U

K

Y

S

E

M

the

12

E

S

Y

K

U

G

Q

C

I

W

O

r

j

u

k

a

h

h

o

u

h

17

X

T

V

Z

L

P

B

F

H

D

J

9

D

H

F

B

P

L

Z

V

T

X

R

20

Y

E

O

I

Q

K

S

M

W

C

G

10

M

C

U

E

I

S

W

G

Y

O

Q

0

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

7

L

R

B

V

D

X

F

Z

J

P

T

7

L

R

B

V

D

X

F

Z

J

P

T

14

W

I

C

Q

G

U

K

Y

S

E

M

20

Y

E

O

I

Q

K

S

M

W

C

G

7

L

R

B

V

D

X

F

Z

J

P

T

T

in the row a=5 using the Excel-formula

=CHAR(65+MOD(E$2*$B4,26)) where the cell E$2 contains 17 and the cell $B4 contains

21 as the decoding key a-1. The formula MOD(E$2*$B4,26) computes the number of the

plain letter T, namely 19. However, converting 19 to its character does not yield the desired T.

The T is stored as 84 which you could see by entering the Excel formula =CODE("T").

Therefore, we first have to add 65 to the 19 in order to translate the 84 eventually into the desired

T using =CHAR(65+MOD(E$2*$B4,26)). In fact, all the upper case letters on Excel are 65

numbers higher than those we are using, the lower case letters on Excel are 97 numbers above

ours (i.e. =CODE("a") yields 97).

Which cracking method should a code cracker use. They are trade-offs in terms of their

efficiency: the gain of not having to determine the most frequent letter in the cipher text for the

brute force approach is at the cost of producing all possible cipher codes. Vice versa, the cost of

detecting the most frequent cipher letter in the first approach is at the gain of producing only one

plain text provided that the most frequent cipher letter turns out to be unique. This is very likely

in English texts and virtually certain in the German language where on average every 5th letter is

an E.

Even if an eavesdropper decides to produce all 12 possible plain texts, they can be generated

with the help of a computer within a few seconds. Therefore, no matter how he decides to crack

the cipher text, it won’t take long. Thus, safer encryptions are necessary. In the next chapter, I

will show you one principle of increasing the safety of a cipher code. I will couple the

Multiplication Cipher with the Caesar Cipher (which produces 26 unique encryptions) to obtain a

15

super encryption that will allow 12*26=312 possible unique encryptions. Are the used 12 unique

encryptions a set number? Or can we even increase the mere 12 unique encryptions for the

Multiplication Cipher by varying the alphabet length? Let’s investigate this in the following

section.

2.4 Varying the Alphabet Length varies the

Number of Good Keys

Using an alphabet length of M=27:

Say for legibility reasons we add a blank symbol as our 27th plain letter. It converts to the plain

letter number 26 so that we now have to encrypt MOD 27. Does the increase of our alphabet

length by 1 increase the number of unique encryptions obtained? Our good-key-criterion

declares those integers to be good keys that are relative prime to 27. Which ones are those?

27=3*3*3, so that only the multiples of the only prime divisor 3 such as a=3, 9 and 27 will not

yield a unique encryption, all the other integers will: The good keys a are therefore

Z27* = {1,2,4,5,7,8,10,11,13,14,16,17,19,20,22,23,25,26}

allowing 18 different unique encryptions, 6 more than before.

Notice that we found the good keys indirectly. We first found the bad keys as the multiples of the

prime divisors of the alphabet length M. Consequently, the good keys are the remaining integers

less than M. Again a perfect task for a computer, especially when we have to find the prime

divisors of bigger integers. (I.e. what are prime divisors of 178247 or of 56272839 ?). Below is

the C++ program that performs the task for us, it just finds all the factors of an entered alphabet

length M by testing all the integers less than M for possible factors. This “brute force” approach

will work fast enough for integers M that have 10 digits or less. For larger integers, however,

dividing by every integer less than M slows the program down enormously. Test it yourself.

One of the major goals of current Mathematics research is to design faster factoring algorithms

as today’s are fairly slow. In fact, the security of i.e. the commonly used RSA Cipher is based on

the relative slowness of such factoring programs. If you are able to invent a fast factoring

algorithm, you will not have to worry about a future job.

//Author: Nils Hahnfeld

//Factoring program

#include <conio.h>

#include <iostream.h>

#include <math.h>

10/15/99

void main()

{

int M, factor ;

clrscr();

16

do

{

cout << "Enter the integer that you want to factor or 0 to exit: M=";

cin >> M;

factor=2;

while(factor <= M)

{

if (M%factor==0) //check all integers less than M as factors

{

cout << factor << endl;

M/=factor;

factor=1;

}

factor++;

}

}while(M!=0);

}

Programmer’s remarks:

Starting with 2, this program checks the integers from

2

to

M-1

as

potential

factors

of

M

in if

(M%factor==0). In such case, divide M by that factor:

M/=factor;

and start checking M/factor for factors

less than M/factor...etc. This process repeats until M

is reduced to 1 and therefore less than the smallest

factor possible, 2.

Can we do even better with M=28 ?

Can we increase the number of unique encryptions by further extending our alphabet? Let’s add

a dot to our alphabet to denote the end of a sentence in the original message. Our alphabet length

of 28 now yields how many unique encryptions? Try it for yourself!

28 equals 2*2*7 so that all the keys that are multiples of 2 or 7 do not and all non-multiples of 2

or 7 do produce a unique encryption: Z28* = {1, 3, 5, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 23, 25, 27} allowing

only 12 different unique encryptions. That is weird! A longer alphabet produces less unique

encryptions. Why is that?

This weirdness is not really weird. What really matters is not the alphabet length M but

rather the number of multiples of the prime factors of M that are less than M: the less

multiples of prime factors (as for the alphabet length of 27), the more a’s produce a unique

encryption and vice versa. Aha, that realization helps a lot, since that also means that prime

M’s produce M-1 unique encryptions. Why is that? Try to explain this, than continue reading!

The reason for that is that a prime number has per definition no prime divisor except for 1 and

itself. Therefore, since there are no other prime divisors and thus no multiples, all integers less

17

than M serve as good keys. Let’s check this for an alphabet length of M=29. As 29 is prime, it

has no divisors except for 1 and 29 and thus there are no multiples as bad keys. Therefore, each

integer

less

than

29

is

a

good

key

MOD

29:

Z29*

=

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28}.

allowing a total of 28 different unique encryptions. Hey, this shows a great way to produce more

unique encryptions which of course makes life harder for an eavesdropper:

Recommendation for more security:

Choose the alphabet length M to be a prime number to make cracking the

cipher text more difficult.

You now understand why cryptographers have an affection for prime numbers. Additionally, you

will learn that the RSA Cipher uses prime numbers as well. They are very special primes as they

must consist of 100 digits or more. It is not difficult to understand that the length of such

numbers requires the usage of computers. Thus, we now go ahead and practice a bit more

computer programming.

Determining the bad keys for a given alphabet length M is a perfect task for a computer. The

following C++ program firstly determines the factors for an entered alphabet length M and

secondly their multiples, the bad keys. Thirdly, listing the good keys would be best done using

C++ vectors or even C-style arrays which you might know. If so please go ahead and modify the

following program. If you don’t know, exercise your patience, later in this chapter I will present

a more elegant program that uses the Euclidean Algorithm to determine the good keys.

This program is an extension of the previous simple factoring program. After finding each factor

of M, I just print them out in

for (j=1;j<factor2;j++){ cout << setw(2) << j*factor << " ";}

I will explain the data type bool and the command setw() after the C++ code.

//Author: Nils Hahnfeld 10-16-99

//Program to find the bad keys

#include <conio.h>

#include <iostream.h>

#include <iomanip.h>

#include <bool.h>

void main()

{

int M, m, j, factor, factor2;

bool prime;

clrscr();

cout << "This program finds the 'bad' keys for an entered alphabet length M."

<< endl;

18

cout <<

"===========================================================================" <<

endl;

do

{

cout << "Enter the alphabet length or 0 to exit: M=";

cin >> M;

m=M; factor=2;

prime=0; //initialization

while(factor <= m)

{

if (m%factor==0)

{

if (factor!=M)

{

cout << "Divisor of "<< M << " =" << setw(3) <<factor<< ". ";

cout << "'Bad' keys: ";

}

else

{

cout << M << " is prime."<< endl;

prime=1;

break;

}

factor2=M/factor;

for (j=1;j<factor2;j++){ cout << setw(2) << j*factor << " ";}

cout << endl;

m/=factor;

while(m%factor==0){m/=factor;} //takes out multiples of factor

factor=1;

}

factor++;

}

cout << "Thus, the 'good' keys are all the ";

if (!prime) cout <<"non-listed ";

cout << "integers from 1 to " << M-1 <<"." << endl << endl;

}while(M!=0);

}

Programmer’s Remarks:

1)

The logic of this program is the same as in the

previous factoring program. However, you can see the

usage of the data type boolean (“bool”, named after

the British Mathematician George Boole [1815-1864]),

which is used if a variable (i.e. prime) can only

attain two possible values: either true (=1) or false

(=0). In order to be able to use the data type

boolean, we have to include the bool.h library in

#include <bool.h>1. Since the bool.h library is very

short I want to show you its contents:

typedef int bool;

const int false = 0;

Modern C++ compiler ( i.e. C++ builder5.0 from Borland) don’t require to include the bool.h library anymore.

Thus, variables of type boolean can be used just like int, char, double or other variables.

1

19

const int true = 1;

In the first line the new data type “bool” is defined

of type “int” so that the (two) bool-variables are

just regular integers. The next two lines then show us

that the variable “false” is defined as “0” and “true”

as “1”. The command const is used as a safety feature

in C++: both variables are constant and can never be

modified in any program.

2) The setwidth command setw() assigns as many spaces

as entered in the parentheses for a numerical output

in order to have a well-formatted output. It has to be

placed after the cout command as in: cout << setw(2)

<< j*factor. In order to be able to use the command

setw() we have to include the iomanip.h library in

#include <iomanip.h>.

2.5 Counting the Number of Good Keys for various

Alphabet Lengths M

– An Introduction to the Euler Function.

Now that we have explored the criteria for unique encryptions and the number of good keys for

certain alphabet lengths, it is the nature of Mathematics to generalize the observations and to set

up an explicit formula for the number of unique encryptions based on the alphabet length M. For

that purpose we have to consider 3 different cases of the alphabet length M

1) If M is a prime number:

We observed in the previous section that the prime alphabet length M=29 yields u=28 unique

encryptions. For the same reason, an alphabet length of M=31 produces u=30 unique

encryptions. Since the number of unique encryptions u is a function of the alphabet length M, we

may write in function notation: u(M) to denote the number of unique encryptions (which equals

the number of good keys) as a function of M. I.e. for M=29 we have u(29)=28. For M=31 we

have u(31)=30.

Remember that a function, per definition, assigns to each x-value one particular y-value. The x values are the ones that we can choose

independently, here the length of the alphabet M. Each y-value is dependent on the choice of x, i.e. the number of unique encryptions u are

dependent on the chosen alphabet length M. Since u can be expressed as a formula that involves M, namely u=M-1, we say that u is a function of

M and write u(M)=M-1.

In general we have the:

Formula for the number of good keys if M is a prime

If the alphabet length M=p is prime, the number of good keys is u(p) = p-1.

2) If M is a prime power, M=pn:

20

Now let’s look back at M=27 as an example where we only have the one prime factor p=3, such

that M=33. How many multiples of 3 will not produce a unique encryption? Those are the 8

integers 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24. Since there are 9 threes (or 9 multiples of 3) in 27 and

therefore 8 threes when counting only up to 26 yielding the 8 listed bad keys. Therefore, we just

need to divide 27 by the only prime divisor 3 and subtract 1 at the end to find the number of bad

keys: 8 = 27/3 – 1.

This principle of finding the number of bad keys holds true for any alphabet length that is a

prime power: There are M/p multiples of p less or equal to M, and therefore M/p - 1 many less

than M. And we are only interested in those integers less than M since we are calculating MOD

M which involves the integers 0 to M-1. Thus, the number of bad keys can simply be found by

dividing the alphabet length M by the only prime divisor p and subtracting 1 from that fraction:

M/p - 1. Let’s write down the

Formula for the number of bad keys if M is a prime power

b(M) = number of bad keys = M/p - 1.

Example1: M=9=32 has the only prime divisor 3 and thus b=9/3 – 1 = 2 bad keys which are 3

and 6 as the multiples of 3 that are less than 9.

Example2: M=81=34 has again 3 as the only prime divisor and thus b = 81/3 – 1 = 34/3 –1 = 33

–1 = 26 bad keys. Those are 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, 39, 42, 45, 48, 51, 54, 57,

60, 63, 66, 69, 72, 75 and 78 as the multiples of 3 that are less than 81.

Our ultimate goal is not to develop a formula for the number of bad keys but rather for the number of good keys.

However, subtracting the number of bad keys from the number of all possible keys (=M-1) yields the number of

good keys. In formula:

u(M) = (M-1) – b(M) using the above formula for the number of bad keys yields

= M-1 - (M/p -1) distributing the minus sign to the terms in the parenthesis yields

= M-1 - M/p + 1 canceling out the 1’s yields

= M - M/p

This turns out to be a handy formula for the number of good keys. However, it can be simplified

further using the fact that we are considering here alphabets of length M that are powers of a

prime p: M=pn for some positive integer n. Thus, our formula simplifies to:

u(M) = pn – pn/p

which simplifies further to

= pn - pn-1.

Therefore,

Formula for the number of good keys if M is a prime power:

If M = pn , the number of good keys is u(M) = pn - pn-1.

Example 1: For M=27=33: Inserting 3 for p and 3 for n in pn - pn-1 yields u(27) = 33 - 32 = 27-9

= 18 which is just what we wanted.

21

Example2: For M=9=32 we have u(9) = 32 - 31 = 9 – 3 = 6 which are the 6 good keys

a=1,2,4,5,7,8.

Example3: For M=16=24 we have u(16) = 24 - 23 = 8 which are the 8 good keys

a=1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15.

Example4: For M= 34 =81, we get u(81) = 34 - 33 = 81 – 27 = 54.

3) If the alphabet length M is a product of two prime

numbers p and q

The last case we have to study is when M is a product of two primes. Combining our three

formulas for the number of good keys, we will then be able to develop a general formula for the

number of good keys for any given alphabet length M.

Let’s start with

Example1: M=26=p*q=2*13. We saw that an alphabet length of M=26 produces 12 unique

encryptions, since the even numbers as multiples of 2 and the 13 are the 13 bad keys. More

precisely: Out of the 25 (= p * q - 1) integers that are smaller than 26, we had 12 (=13-1)

multiples of 2 {2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18,20,22,24} and the 1 (=2-1) multiple of 13 {13} as bad

keys, so that 25-12-1=12 good keys are remaining:

a = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25

Notice that u(26) = 12 = 25-12-1 = (p*q - 1) – (p-1) - (q-1)

Example2: For M=10=5*2, we obtain u(10)=4 good keys which are obtained by crossing out

the 4 (=5-1) multiples of 2 and the 1 (=2-1) multiples of 5 as bad keys:

a = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Notice that again u = 4 = 9 – 4 –1 = (p*q - 1) – (p-1) – (q-1)

Example3: For M=15=5*3, we obtain u(15)=8 good keys which are obtained by crossing out

the 4 (=5-1) multiples of 2 and the 2 (=3-1) multiples of 5:

a = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Notice that again u = 8 = 14 – 4 – 2 = (p*q - 1) – (p-1) – (q-1)

The number of good keys can always be computed by u(p*q) = (p*q - 1) - (p-1) -(q-1). This

formula can be simplified into the product of two factors. Here is how:

u = (p*q - 1) - (p-1) – (q –1) getting rid of the first two parentheses yields

= p*q -1 - p + 1 – (q –1)

the two 1’s cancel each other out yielding

= p*q – p – (q –1)

factoring the p yields

= p*(q-1) – (q –1)

(q-1) in both terms can be factored yielding

= (q-1) * (p –1)

which can also be written as

= (p-1) * (q –1)

22

Formula for the number of good keys if M is the product of

two primes:

The number of good keys is u(M) = u(p*q) = (p-1)*(q-1).

Example4: If M=39=3*13=p*q, then the formula yields u(39) = (3-1)*(13-1) = 2*12 = 24.

You can verify this as follows: out of the 38 (=p*q-1) integers that are less than 39, we first cross

out all the 12 (=13-1) multiples of 3 {3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27,30,33,36} and then cross out the 2

(=3-1) multiples of 13 {13,26} resulting in 38 – 12 – 2 = 24 good keys.

Example5: If M=65=5*13=p*q, then the formula yields u(65) = (5-1)*(13-1) = 4*12 = 48.

You can verify this as follows: out of the __ integers that are less than 65, we first cross out all

the ___ multiples of __ and then cross out the __ multiples of __ resulting in ______ = 48 good

keys.

A summary of our explorations for the number of good keys

shows:

1) u(p) = p - 1,

if M is prime M=p.

n

n

n-1

2) u(p )= p - p ,

if M is a power of a prime M= pn.

3) u(p*q) = (p-1)*(q-1), if M is a product of two primes M=p*q.

Credit goes to the Swiss Mathematician Leonard Euler (pronounced “Oiler”, 1707-1783). He investigated these

number properties and was the first one to come up with a function, Euler’s -function, also called Euler’s Totient

function, that determines the number of integers that are relative prime to a given integer M. It is a function that is in

the heart of Cryptography and used i.e. for the RSA encryption. The following table shows the numbers relative

prime to M for the first 21 integers.

M

(M)

2

1

3

2

4

2

5

4

6

2

7

6

8

4

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

8 12 10 4 12 6 8 8 16 6 18 8 12

Similar to our notation, the properties of Euler’s -function that computes the number of integers

that are relatively prime to M and wrote similarly to our notation:

Euler’s -function:

1) (p) = p-1

2) (pn) = pn - pn-1

3) (p*q) = (p-1)*(q-1)

4) (n*m) = (n) * (m)

for a prime p.

for a prime power pn.

for two distinct primes p and q.

when n and m are relatively prime. It describes the multiplicative

property of .

We have explored the first three properties already, however, the 4th property is new - but not

totally new. I want to show you an example where we used it already. Say M=26=2*13=n*m.

Since n and m are two distinct primes, they certainly are relative prime, so that the condition for

property 4) is fulfilled. We obtain (2*13) = (2) *(13). From property 1) we know that

23

(2)=1 and (13)=12, and consequently, (2*13) = (2)*(13) = 1*12 = 12 which is exactly

property 3). Thus, property 4) yields nothing new if our alphabet length is the product of two

primes. However, it turns out to be indispensable when M is not the product of two primes, but

say a product of a prime and a prime power.

Example1: If M=24=3*8=3*23, then

(24) = (3*23)

using property 4) yields

= (3)*(23).

using properties 1) and 2) yields

3 2

= (3-1)*(2 -2 )

= 2*4

= 8.

For a check: the eight integers 1,5,7,11,13,17,19,23 are relative prime to 24 and thus the good

keys for M=24.

Even products of 3 primes or prime powers like 30 or 60 can now be dealt with due to the 4th

property:

Example2: If M=30=2*3*5, then

(30) = (2*3*5)

using property 4) yields

= (2)*(3*5)

again property 4) yields

= (2)*(3)*(5)

now using property 1) yields

= 1*2*4

= 8.

For a check: the same eight integers 1,5,7,11,13,17,19,23 are relative prime to 30 and are thus

the good keys for M=30.

Example3: Now, it is your turn. If M=60=22*3*5, then

(60) = (22*3*5)

using property __ yields

= (22)*(3*5)

using property __ yields

2

= (2 )*(3)*(5) using properties __ and __ yields

= (22 – 21)*2*4

= 2*2*4

= 16.

You noticed, that the multiplicative property of Euler’s -function, expressed in property 4), is

used to decompose any integer M into its prime factors or prime power factors to then apply the

first two properties to each prime or prime power. This eventually enables us to calculate the

number of integers that are relative prime to these primes and prime powers. Multiplying such

answers yields the number of good keys for any given alphabet length. The given examples show

you the calculation process. Notice, that property 3) became useless for the calculation process

since factors that are relative prime are separated via property 4). Subsequently, is computed

by property 1) if such factors are primes or by property 2) if they are prime powers.

Before we conclude this section with the highlight of creating a sole formula for (M) from these

four properties, we will consider 2 examples for each of the 4 properties of Euler’s -function. I

will complete the first ones and leave the second ones for you as exercises.

24

Examples for property 1): 3 and 5 are two primes.

(3)=3-1=2 as 1 and 2 are relative prime to 3.

(5)=_____ as 1,2,3,4 are relative prime to 5.

Examples for property 2): 8 and 25 are prime powers.

(8)= (23)=23 -22 =4 as 1,3,5,7 are relative prime to 8.

(25)=____________ as all integers from 1 to 24 except for 5,10,15,20 are

relatively prime to 25.

Examples for property 3): 15 and 21 are products of two primes.

(15)=(3*5)=(3-1)*(5-1)=2*4=8 as 1,2,4,7,8,11,13,14 are relative prime to 15.

(21)=________________________ as 1,2,4,5,8,10,11,13,16,17,19,20 are

relative prime to 21.

Examples for property 4): 24 and 28 are products of primes and prime powers.

(24) = (23 *3) = (23)*(3) = (23-22)*(3-1) = 4*2 = 8 as 1,5,7,11,13,17,19,23 are

relative prime to 24.

(28) = _____________________________

as 1,3,5,9,11,13,15,17,19,23,25,27 are

relative prime to 28.

Now, let’s come to the highlight of this section: I will show you in a few steps how to compute

(M) for any M from one equation instead of combining the four properties? All we need to

know are the prime divisors of M, but we don’t even need to know how often a prime number

divides M. I.e., for M=27 we just need to know that 3 is a prime divisor of 27 but not how

often it divides 27. While deriving the formula for M=60=22*3*5 in the left column I will

deduce simultaneously the explicit formula for M=p12*p2*p3 with p1 being the first prime factor

2, p2 being the second prime factor 3 and p3 being the third prime factor 5 in the right column.

We know already that:

(60) = (22*3*5)

= (22-21)*(3-1)*(5-1)

(M) = (p12* p2* p3)

= (p12- p11)*( p2-1)*( p3-1).

For the purpose of setting up an explicit formula for (M), we now try to give the three factors

(in parentheses) the same format. We factor p1=2 yielding

= 2*(2-1)*(3-1)*(5-1)

= p1* (p1- 1)*( p2-1)*( p3-1).

The three factors in the parentheses already have the same desired format, however, the single 2

destroys it. The ultimate trick to yet produce the same format is factoring: from each parentheses

we factor the first integer (which is a divisor of M) and obtain:

(60) = 22*(1 -1/2) * 3*(1 -1/3) * 5 * (1 -1/5)

(M) = p12 * (1 -1/ p1) * p2*(1 -1/ p2) * p3 * (1 -1/ p3)

= 22*3*5*(1 -1/2)*(1 -1/3)*(1 -1/5)

= p12* p2* p3*(1 -1/ p1)*(1 -1/ p2) * (1 -1/ p3)

= 60*(1 -1/2)*(1 -1/3)*(1 -1/5)

= M * (1 -1/ p1) * (1 -1/ p2) * (1 -1/ p3).

25

This is it. Notice in the last row that all we need to know are the prime factors p of M without

knowing how often they occur. We then write them in the form (1-1/p), multiply them and that

product by M yielding (M). On the right we ended up with the explicit formula for (M) when

M consists of one prime power and two primes. It surely acquires this simple form for any

number of primes or prime powers. Notice, that all we need to find are the different primes, say

p1, p2,..., pn, as our explicit formula for the number of unique encryptions appears to be:

Formula for the number of good keys for any alphabet

length M:

For an alphabet length M, there are (M) = M * (1- 1/p1) * (1- 1/p2) *…* (1- 1/pn) good keys

where each pi is a prime divisor of M.

It is really enjoyable to use this simple formula as we just need to find all prime divisors of M

and don’t have to worry about how often they occur. Therefore, a simple prime check program

would be sufficient to find the divisors p of M. We then set up the factors of the form (1- 1/p),

multiply them and eventually multiply that answer by M.

Example1:

Say M=180, then a prime check program yields the prime factors 2,3 and 5, so that

(180) = 180 * (1-1/2) * (1-1/3) * (1-1/5)

= 180 * (1/2) * (2/3) * (4/5)

= 90 * (2/3) * (4/5)

= 60 * (4/5)

= 48

Example2:

Say M=360, since 360=2*180 the prime factors are again 2,3 and 5, so that

(360) = 360 * (1-1/2) * (1-1/3) * (1-1/5)

= 360 * (1/2) * (2/3) * (4/5)

= 180 * (2/3) * (4/5)

= 120 * (4/5)

= 96

Example3 is for you:

Say M=90, since 90=____ the prime factors are _______, so that

(90) = 90 * (1-1/__) * (1-1/__) * (1-1/__)

= 90 * ____________________

= _______________

= _______________

= ___

Of course, I could have computed the answers in the above examples right away but I wanted to

give you the chance of brushing up on your skills to multiply fractions. A little computer

26

program turns out to be again very valuable as the number of good keys can be easily determined

by first finding all prime factors of M to then use the above explicit formula.

//Author: Nils Hahnfeld 10-16-99

//Program to determine

(M)using

M*(1-1/p1)*(1-1/p2)*...

#include <iostream.h>

#include <conio.h>

void main()

{

int factor, M, m;

float phi;

clrscr();

cout << "This programs uses M*(1-1/p1)*(1-1/p2)*... to calculate

phi(M)."<<endl;

cout <<

"==============================================================="<<endl;

do

{

cout << "Enter M to find the number of 'good keys' or 0 to exit: M=" ;

cin >> M;

cout << endl << "Prime Factor(s) are : " ;

m=M; factor=2;

phi= (float) M; //casting: from integer to float data type

while(factor <=M)

{

if (M%factor==0)

{

cout << factor << " ";

M/=factor;

while (M%factor==0) M/=factor; //takes out multiple factors

phi*= (1- 1/(float)factor);

}

factor++;

}

cout << endl << "phi(" << m <<")="<< phi << endl << endl << endl;

}while(M!=0);

}

Programmers remarks:

This program is an enhanced version of thr previous

one that found the bad keys as factors of M for us. If

a factor p is found we now additionally form the term

1- 1/p and multiply it to the other terms in phi*= (11/(float)factor) to eventually obtain phi.

Notice in this program that phi and M are declared as

2 different data types, yet the value of the integer

(int) variable M can be assigned to the real number

(float) variable phi in phi= (float) M; All I needed

27

to do is to write the new data type (here float) in

parenthesis right in front of the integer variable M.

This process is called type-casting and also works

when converting between any other numerical data

types. In that case you have to be aware that when you

convert from a float or a double to an integer (that

is from more a precise to a less precise data type)

the decimals are simply cut off: i.e. 3.1415927

becomes the integer 3 and we are losing precision. The

other time that we are casting in

phi*= (11/(float)factor); we don’t give up any precision (and

therefore information) as we convert from the integer

typed variable factor to the more precise real number

typed variable phi.

2.6 Introduction to Euler’s Theorem – Usage of the

Good Keys

In this section, we will discover Euler’s Theorem which is the basis for the RSA encryption that I

will introduce in chapter 5. It will be quite easy for you to grasp it since it solely deals with

properties of the familiar good keys. Let’s recall first what we know already about them.

2.6.1 Good Keys have different Orders

A brief review: In section 2.2 we observed in the reduced multiplication table MOD26 that each

encoding key that produces a unique encryption was called a good key and possesses a unique

inverse a-1, the decoding key. You can verify this by finding exactly one 1 in each row that is

produced by the multiplication of the encoding keys with its inverse a-1. Recall that an inverse of

a is that particular integer a-1 that yields 1 when multiplied by a.

Decoding key a-1

*

1

3

5

1 3 5 7 9 11 15 17 19 21 23 25

1 3 5 7 9 11 15 17 19 21 23 25

3 9 15 21 1 7 19 25 5 11 17 23

5 15 25 9 19 3 23 7 17 1 11 21

Encoding key a

28

7

9

11

15

17

19

21

23

25

7

9

11

15

17

19

21

23

25

21

1

7

19

25

5

11

17

23

9

19

3

23

7

17

1

11

21

23

11

25

1

15

3

17

5

19

11

3

21

5

23

15

7

25

17

25

21

17

9

5

1

23

19

15

1

5

9

17

21

25

3

7

11

15

23

5

21

3

11

19

1

9

3

15

1

25

11

23

9

21

7

17

7

23

3

19

9

25

15

5

5

25

19

7

1

21

15

9

3

19

17

15

11

9

7

5

3

1

Notice also that each good key occurs once in each row as well. Therefore, each row below the

top row is just a rearrangement of the integers in the top row, which is also called a permutation.

In other words: the integers 1,3,5,7,9,11,15,17,19,21,23,25 appear exactly once in each row.

Moreover, we learned in section 2.2 that the only keys that are inverse to themselves, which

means that the encoding key equals the decoding key, are 1 and 25 because 1*1=12=1 MOD 26

and 25*25=252=1 MOD26. Notice that as there are no other 1’s on the diagonal there are no

other keys that are inverse to themselves. Therefore, raising any other key except for 1 and

25 to the second power will not yield 1, however, if we raise to powers greater than 2, will

we be more successful? Will we be able to raise the good keys to powers that yield 1 MOD

26? Might there even be one 'universal’ exponent that produces 1 for each good key a? We

will check this now in detail for the good keys in Z26*, and then briefly for those in Z27* and

Z28*.

For our exponent inspection, we need a new vocabulary in order to denote that particular power

of a good key that yields the first 1.

Definition of the order of a good key:

We raise the good key a to the power of 1, 2, 3, etc.: a1, a2, a3, … We stop when the first power

yields 1 (which is guaranteed to happen for each good key and will be proved in the upcoming

Euler’s Theorem). That exponent whose power yields the first 1 is called the order of a.

or equivalently:

If as=1 for the smallest positive integer s, then “the order of the good key a is s.”

So, let’s find the orders of the good keys MOD 26.

For a=3:

32=9 and 33 = 3 * 32 = 3 * 9 = 27 MOD 26 = 1. Since all calculations are performed MOD 26,

we may just write 33=1 and therefore as a chain display:

31 -> 32 -> 33 MOD 26 or even simpler:

3 -> 9 -> 1

29

Here, the order of the good key a=3 is 3 since 33=1, which equals the length of the chain

(why?). Therefore, 36 equals also 1 since 36 = (33)2 = 12 =1. For the same reason: 312=1.

Although the exponents 6 and 12 also yield 1, none of them is the order of a=3 as none of them

is the smallest exponent that yields 1. 3 is therefore the uniquely defined order of a=3. The fact

that 36, 39 and 312 all equal 1 can easily be seen by extending the above chain display as follows:

3 -> 9 -> 1 -> 3 -> 9 -> 1 -> 3 -> 9 -> 1 -> 3 -> 9 -> 1

(31 -> 32 -> 33 -> 34 -> 35 -> 36 -> 37 -> 38 -> 39 -> 310 -> 311 -> 312)

Because of the repetitive or cyclic nature of the powers of 3, the chain can simply be displayed

as:

3

-> 9 -> 1

and the period of this chain, namely 3, equals the order of the key a=3.

For a=5:

Since 5*5=25 and 5*25=21 and 5*21=1 we get 5*5*5*5=54=1. Therefore, 4 is the order of 5

which again equals the period of the chain:

5 -> 25 -> 21 -> 1

Furthermore, 58=(54)2=12=1. Explain why 512 =1, 516 =1, 520 =1 yourself using the chain

display.

You can practice your MOD-calculation skills by computing 54=1 in an alternative way: Since 52

= 25 = -1 MOD 26, we obtain 54 = (52)2 = (-1)2 = 1 MOD 26.