The Poetics of Fiction : poetic influence on the language of Apuleius

advertisement

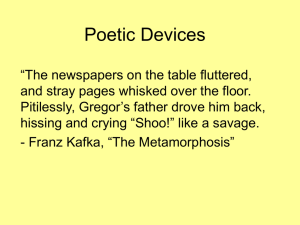

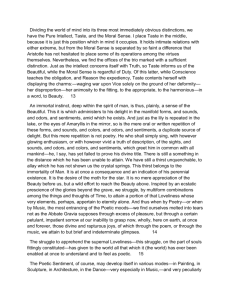

1 The Poetics of Fiction : poetic influence on the language of Apuleius’ Metamorphoses 1 1.Introduction : poetic language in Apuleius’ novel. My topic is the role of poetic language in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses, and how that role has been differently perceived in Apuleian scholarship. The Met. is the Apuleian work in which poetic elements figure most prominently, for which its kinship with poetry through its character as a literary fiction is a primary explanation. Unlike the rhetorical works of Apuleius (the Apologia, Florida and De Deo Socratis), which are full of verse citations, his novel (in contrast too with the prosimetric Satyrica of Petronius or several of the Greek novels) 2 does not engage in extensive overt citation of real or imaginary poetic texts; the only verses quoted in the work are two short fictional oracles, the supposed elegiac response of Apollo at Miletus (4.33.1-2), and the iambic distich which serves as the all-purpose answer for the charlatan priests of the Dea Syria (9.8.2). What we find, as in the manner of the possibly contemporary Daphnis and Chloe, 3 is the consistent embedding of poetic diction and allusion into the fundamental texture of its style. The examples discussed in this piece (section 3) come from especially marked moments of the novel’s plot, since it is at such moments that poetic allusion and language is likely to come to the fore, but poeticism is a universal streategy in the Met.; this piece argues that traditional views about poetic elements in the novel as evidence of post-classical Latinity (section 2) can be superseded by a more positive and contextualised approach which opens up new perspectives on Apuleius’ place in the history of Latin prose (section 4). 2. Poeticism and decline : some views of Apuleian style. 1 It gives me especial pleasure to dedicate this piece to Michael Winterbottom, in recognition of his own great personal contribution to the study of Latin prose and in warm thanks for his personal kindness and encouragement in my own work over the years. I am most grateful to the editors for their helpful comments. 2 On the poetry in Sat. see Connors (1998); on poetry in the Greek novel see Bowie (1989). 3 Cf. e.g. Hunter (1983). 2 The admixture of poetry and prose in the style of the Met. is now considered one of its most subtle and valuable aspects, but this was was not always so in the history of scholarship. Until recently, this feature was commonly regarded as symptomatic of the novel’s ‘late’ and ‘post-classical’ character. Take, for example, the opening page of Löfstedt’s Late Latin : ‘In literature, the great Roman tradition ends with Tacitus. Apuleius, born about 125, is already the representative of a different style : shifting, iridescent, borrowingly freely from poetry, strongly influenced by Greek and, in the Metamorphoses, by the realistic narrative style of the prose romance, from which it draws certain popular elements of its language’. 4 The implication that a prose style incorporating poetic elements was late and post-classical is clear in Bernhard (1927), in some ways still the standard handbook on Apuleian style. Bernhard’s chapter on poetic and rhetorical colour in the Met. begins with a clear ideological statement : ‘ In the period of good Latinity a firm and immediately recognisable difference persists between the diction of poetry and that of prose. The poet can make use of a series of expressions, of images and also of syntactical poeticisms which are strongly avoided in good prose. In the long term the difference between these two kinds in this distinguishing feature, as known in the classical period, could not be maintained’. 5 Bernhard sees Apuleius as more poetic than all Latin prose writers, but regards this as a symptom of post-classical Latin prose style through contemporary declamation and reading of the poets, and as a major step on the way to Late Latin. A partial exception to this view of Apuleian poeticism as separate from classical Latinity is the almost simultaneous work of Médan (1925). Médan is primarily motivated to defend Apuleian style against the famous attack of Norden in Die Antike Kunstprosa, an attack which concluded with the extraordinary assertion that Apuleius had in effect prostituted Latin : ‘The Roman language, a serious and worthy matron, has become a prostitute; the language of the brothel has stripped away her chastity.’ 6 Médan’s conclusions on Apuleian poeticisms, seen as so inappropriately exotic by the severe Norden, are rather more sympathetic : ‘In using poetic terms … Apuleius means once again to spread out in front of his readers his profound knowledge of the Latin language, extending to its most refined nuances and 4 Löfstedt (1959 : 1) Bernhard (1927 : 188), my translation. 6 Norden (1898 : 600-1), my translation. 5 3 most rare pecularities’ . 7 Like so many writers on Apuleian style, Médan views it as exotic but interesting, and poeticisms as mere decoration : ‘we will now see him insert in his style, just as a goldsmith encrusts gold or silver with precious stones, expressions which are drawn from the poets that came before him and which have undergone only slight transformations, or again borrow from the poetic palette the most subtle colours, to add to his prose light, almost imperceptible touches which link him to the style of the poets’. 8This rhetoric of the decorative arts suggests that what we are dealing with is pure surface and ornament; for Médan this is not the robust, manly prose of Cicero but a late and precious sub-species. 9 As Löfstedt (to do him justice) implied, Apuleius surely comes too early for ‘late Latin’ to be a major issue : he was after all born in about 125, during, or possibly just after, the lifetimes of both Juvenal and Tacitus.10 It is worth pausing for a moment on the the analogies of Apuleius’ Latinity with that of Tacitus; though this is not an issue commonly pursued in studies of the style of either author, it is in fact rewarding to compare the two greatest Latin prose stylists of the second century AD. Both authors use appropriately different styles for works in different genres : Apuleius’ Apologia is much more Ciceronian than his other works, imitating the high style of Ciceronian forensic oratory, 11 just as Tacitus’ Dialogus uses a perceptibly Ciceronian style in homage to its models, Cicero’s dialogues on oratory, in contrast with the more Sallustian style of his other works.12 Notoriously, this was thought to be so problematic that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there was widespread doubt that the Dialogus was a genuine work of Tacitus; 13 this has interesting analogies with the current debates about the authenticity of the lesser works ascribed to Apuleius, particularly the drier De Mundo and De Platone.14 In particular for our current purposes, the high style of Tacitus’ Annales, like the very different high style of Apuleius’ Metamorphoses, gains many effects from the use of poetic vocabulary, as has often been observed. 15 Though many would agree that Tacitean Latin is idiosyncratic, few would wish to categorise it as decadent, and most would wish to 7 Médan (1925 : 197), my translation). Médan (1925 : 244), my translation). 9 There is an interesting link here with the concept of the ‘jewelled style’ used positively to describe the Latin poets of Late Antiquity by Roberts (1989 : 9-37) 10 Cf. Harrison (2000: 3). 11 Cf. e.g. Callebat (1984) 12 Cf. Mayer (2001: 27-31). 13 Cf. Mayer (2001) 18-22. 14 For this debate see Harrison (2000: 174-80), in favour of authenticity.. 15 Especially, like Apuleius, from Vergil : for work on this see Miller (1961-2), (1986), and Baxter (1971),(1972). 8 4 view it as a carefully constructed and literary Kunstprosa. It seems inconsistent to view Apuleius in a substantially different light. Another and perhaps more long-standing prejudice which is still occasionally found in scholarship is that of Apuleius’ stylistic barbarism. This has been characteristically articulated through the conveniently marginalising concept of ‘African Latin’, the thesis that the Latin of Apuleius and other writers of known African origin in the Roman Empire represents a separate regional, barbarised and inferior dialect. This is not the place for a discussion of the history of this contested idea, which begins in the Renaissance, gains some force in the late nineteenth century, and is still vestigially alive today; 16 for myself, I would not wish to deny the possibility that the spoken Latin of Rome’s African territories preserved aspects of the language of their original settlers which could later be viewed as archaic, and that this might make some small contribution to an overall assessment of Apuleian Latinity. 17 I would certainly wish to deny that Apuleius’ use of archaisms is primarily a sign of his regional orientation; it is much better seen (as many have argued) 18 as a consequence of the archaising movement in Rome which seems to have begun under Hadrian, famously said to have preferred Ennius to Vergil and Coelius Antipater to Livy (SHA Div.Hadr.16.6), and was promoted by Fronto (only accidentally a fellowAfrican) in the following generation under the Antonines, the period of Apuleius’ intellectual formation. Löfstedt’s emphasis on the popular elements in Apuleius’ language points to another factor which has been highly influential in this area, Apuleius’inclusion of popular speech in his novel. Especially significant here has been the work of Callebat 19 . In his massive 1968 thesis Callebat focussed on the use made by Apuleius of everyday spoken Latin, suggesting that the style of the novel operated on various levels from the poetic to the sub-literary, but that its reflection of contemporary Latin was most important; he then promised a further full treatment of the more artistic and poetic aspect of Apuleian style, which was not then forthcoming. The overall effect of the absence of this sequel has been to foreground the issue of Apuleius’ relationship to contemporary Latin usage, and in effect to play down the element of artistic and poetic prose. This certainly unintended imbalance was partly redeemed in a later 16 See Brock (1911 : 161-261) and my discussion in Harrison (2002). This is essentially the thesis of Petersmann (1998). 18 See e.g. Marache (1952), Steinmetz (1982). 19 Callebat (1968) and (1998). 17 5 article, where he dedicated a section to the use of poetry, and argued that this element in Apuleian style was one of the features which linked it to the great tradition of Latin Kunstprosa : ‘Written in the tradition of post-Ciceronian artistic prose, the contamination shown in the Metamorphoses between the code of poetry and the code of prose reveals too its original links with the very establishment of a literary aesthetic which gave the credit of artistic discourse to prose’. 20 Callebat’s unintended downplaying of poetic elements has in effect led in the current generation of scholarship to an appreciable sub-branch of Apuleian studies, the detecting of poetic language and structures in the style of the Metamorphoses. 21 This has also been the most flourishing period of the Groningen project to produce commentaries on the Metamorphoses of Apuleius, in which the noting of Apuleian imitation of poetic models has been an important element amid a much more detailed analysis of the language of the novel in context. 22 These modern treatments of poetic imitation in Apuleius vary from the syntactical and lexical to the broadly thematic, but in general have a common viewpoint on the function of poetic allusion in Apuleius, namely that in the Metamorphoses at least we are often dealing with detailed and purposeful intertextuality which not only uses words and phrases from the poetic register but also deploys them in deliberate allusions to key literary texts, allusions which can have powerful influence on literary interpretation. In this respect such investigations draw much from and can clearly be associated with what might be called the ‘intertextual turn’ in the study of Latin poetry in the 1980’s; 23 this has been one of the factors in the reorientation of Apuleius’ novel since 1970 from a specialist and marginal interest to a central text of Latin literature which appears on the syllabuses of many universities. 3 : The Power of Prayer : Apuleian poeticism in action. Here I want to bring out by analysis of several passages one way in which poetic allusion and language can function to create a particular kind of literary tone in 20 Callebat (1994 : 167), my translation. Walsh (1970) here is pioneering; see more recently Finkelpearl (1998), and for other references see Harrison (1999) xxxiv-v. 22 Especially Hijmans et al (1995), Zimmerman (2000), van Mal-Maeder (2001), Keulen (2003; a preliminary version of a commentary on the whole of Book 1) and Zimmerman et al. (2003), and the two associated volumes of essays – Hijmans and van der Paardt (1978) and Zimmerman et al. (1998). 23 For the most representative discussion see Hinds (1998). 21 6 the Met. In some previous work I have concentrated on how the lower genre of the novel appropriates for more entertaining and low-life purposes the serious and elevated diction and themes of higher genres such as epic; this is an important part of the novel’s self-consciousness and sense of its place in the generic hierarchy. 24 Much of the novel’s relationship to epics such as the Aeneid and the Odyssey indeed consists of parody. But there are also moments where epic is deployed for its power and elevation, especially in the description of passion. The use of the characterisation of Dido in the Aeneid as an analogue for the high emotional states of Psyche and Charite is a well-known example in the Met. 25 Here I would like briefly to consider a further case where poetic language contributes to impressive and heightened scenes in the novel, and where we can see the diction of Apuleian prose not only employing existing poetic terms but creating new ones by analogy with poetic models. These are passages where the novel’s characters interact with divine figures, usually in prayer, and where gods speak to them, epic-style scenarios where one might indeed expect more elevated and dignified language to be used. They have been recently closely examined for their connection with the language of Roman prayer, but their debts to poetic language have not yet been fully considered 26. At 6.2 Psyche, in the temple of Ceres, prays to the goddess in her distress : Tunc Psyche pedes eius advoluta et uberi fletu rigans deae vestigia humumque verrens crinibus suis multiiugis precibus editis veniam postulabat: ‘Per ego te frugiferam tuam dexteram istam deprecor, per laetificas messium caerimonias, per tacita secreta cistarum, et per famulorum tuorum draconum pinnata curricula et glebae Siculae sulcamina et currum rapacem et terram tenacem et inluminarum Proserpinae nuptiarum demeacula et luminosarum filiae inventionum remeacula et cetera quae silentio tegit Eleusinis Atticae sacrarium, miserandae Psyches animae supplicis tuae subsiste…’. 24 See Harrison (1990), (1997) and (1998), See the material gathered in Harrison (1997 : 62-7). 26 For the way in which these passages make prominent use of the assonance, alliteration and other forms of euphony associated with Roman prayer-language, see the full analyses in Pasetti (1999), and the comments on individual elements in Facchini Tosi (1986). A few of the details found here on 6.2 and 6.4 can be found in the smaller-scale commentaries of Kenney (1990) and Moreschini (1994), but I have also here been able to make use of the material in the forthcoming commentary on Cupid and Psyche of Zimmerman et al (2003); I am most grateful to my fellow-authors for this. On Book 11 none of the exisiting commentaries provide much help on these issues. 25 7 The poeticising elements in this passionate passage are underlined. Some have recognisable origins in extant verse texts, ranging from the archaic to the more recent. Senecan tragedy is prominent, not for the only time in the novel; in Book 10 the account of the Phaedra-type murderess uses the language of Seneca’s Phaedra, as scholars have repeatedly noted, stressing her literary characterisation.27 Here the phrase uberi fletu rigans picks up Seneca Med. 388 oculos uberi fletu rigat; the mad and violent grief of Medea, soon to issue in death and destruction, makes a contrast with the softer and more humble despair of Psyche, but nevertheless stresses her extreme emotional state, and Medea is not the only tragic heroine with whom Psyche can be implicitly compared through intertextual echoes. 28 Seneca also seems to be evoked in the description of the Underworld as terram tenacem, presumably indicating its power to retain Proserpina after her kidnap by Pluto; cf. Seneca Phaed. 625 f. regni tenacis dominus et tacitae Stygis / nullam relictos fecit ad superos uiam. This is especially pointed in this prayer of Psyche to Proserpina’s mother, evoking her daughter’s suffering in a plea from a figure of her daughter’s age. In all these cases, it can be argued that an original literary context is recalled in order to add an extra literary dimension to Psyche’s words. Her speech also contains poeticisms which see more inert and generalised : the use of vestigia for ‘feet’ is a common Latin poeticism found in Catullus, Vergil and Ovid, 29 while the further compound laetificus can be traced back to Ennius. 30 Other evidently poetic words are not found before Apuleius, and may represent either Apuleian coinages or allusions to poetic texts now lost : the noun sulcamina, found only here, may well be coined for euphonic reasons, 31 but represents a type of coinage much favoured by Lucretius, Vergil and Ovid as well as Apuleius, though also found in earlier prose authors 32, the similarly unparalleled adjective inluminus belongs to a type of negative adjective derived from a noun which Apuleius seems to coin elsewhere, and may like innumerus (Apol.9,36, Flor.8.2; cf. Lucr.2.1054, Vergil Aen.11.204) look back to an earlier poetic use, and the hapax demeacula is another coinage of lofty tone, matching the likely meacula at 1.4 and poetic words such as spiraculum 33. The overall effect 27 For bibliography and details see Zimmerman (2000: 430-1). See e.g. Schiesaro (1988), Mattiacci (1993). 29 Cf. Harrison (1991 : 228) on Aeneid 10.645-6. 30 Cf. Skutsch (1985 : 728). 31 Cf. Facchini Tosi (1986 : 126), Pasetti (1999: 254, n. 24). 32 Cf. Harrison (1991: 197) on Aeneid 10.493-4 with bibl. there cited. 33 Cf. Keulen (2003) 124. 28 8 of this vocabulary is one of grandeur and elevation suitable for addressing the majesty of a god, and the poetic colour is highly appropriate to this context. Not long afterwards Psyche goes through the same process with Juno, asking her too for help (6.4) : ‘Magni Iovis germana et coniuga, sive tu Sami, quae sola partu vagituque et alimonia tua gloriatur, tenes vetusta delubra, sive celsae Carthaginis, quae te virginem vectura leonis caelo commeantem percolit, beatas sedes frequentas, seu prope ripas Inachi, qui te iam nuptam Tonantis et reginam deorum memorat, inclitis Argivorum praesides moenibus, quam cunctus oriens Zygiam veneratur et omnis occidens Lucinam appellat, sis mei extremis casibus Iuno Sospita meque in tantis exanclatis laboribus defessam imminentis periculi metu libera. Quod sciam, soles praegnatibus periclitantibus ultro subvenire.’ As Kenney points out, 34 Psyche begins by addressing Juno with an epic formula honouring her unique status as wife and sister of Jupiter, recalling those used by Juno of herself in indignant self-praise and used to her by Jupiter in high persuasive mode in the Aeneid (1.45-6 ast ego, quae divum incedo regina, Iovisque / et soror et coniunx, 10.607 o germana mihi atque eadem gratissima coniunx); this allusion is typically varied by the apparent Apuleian coinage coniuga, with its markedly artificial flavour 35. Psyche’s flattery is literary : she addresses Juno with the Vergilian words the goddess has used of herself and with which she has been wheedled by her husband/brother at a climactic point in Rome’s greatest poem. As in the previous passage, this actively intertextual material is accompanied by further poeticisms aimed at striking a grand note. The epithets celsus and inclitus are both poetic and archaic, 36 while vagitus (found only here in Apuleius) occurs largely in poetry, 37 the conjunction beatae sedes picks up Aeneid 6.639 sedesque beatas, and both the simplex pro composito memorare 38 and the metaphor of exanclare 39 similarly reflect high poetic style. 34 Kenney (1990 : 194) Callebat (1968 : 244) argues that it is a colloquialism, but in its few occurrences outside this passage it is primarily a marked inscriptional usage (TLL 4.321.71ff). 36 See respectively Harrison (1991 : 142) on Aeneid 10.261-2 and Skutsch (1985 : 302) on Ennius Ann.146. 37 Its first two instances are Lucretius 5.226 and Vergil Aeneid 6.426. 38 Cf. Harrison (1991: 101)) on Aeneid 10.149. 39 See Keulen (2003) 281-2 with literature on its poetic origin (especially common in archaic Roman tragedy). 35 9 At 11.2 Lucius-ass, alone on the sea-shore at Cenchreae, prays to the moongoddess (as he then sees her) for retransformation into a human form : ‘Regina caeli, — sive tu Ceres alma frugum parens originalis, quae, repertu laetata filiae, vetustae glandis ferino remoto pabulo, miti commonstrato cibo nunc Eleusiniam glebam percolis, seu tu caelestis Venus, quae primis rerum exordiis sexuum diversitatem generato Amore sociasti et aeterna subole humano genere propagato nunc circumfluo Paphi sacrario coleris, seu Phoebi soror, quae partu fetarum medelis lenientibus recreato populos tantos educasti praeclarisque nunc veneraris delubris Ephesi, seu nocturnis ululatibus horrenda Proserpina triformi facie larvales impetus comprimens terraeque claustra cohibens lucos diversos inerrans vario cultu propitiaris, — ista luce feminea conlustrans cuncta moenia et udis ignibus nutriens laeta semina et solis ambagibus dispensans incerta lumina, quoquo nomine, quoquo ritu, quaqua facie te fas est invocare: tu meis iam nunc extremis aerumnis subsiste, tu fortunam collapsam adfirma, tu saevis exanclatis casibus pausam pacemque tribue; sit satis laborum, sit satis periculorum.’ This prayer is again full of poetic language, again aiming at an elevated effect at this climactic moment in the plot. Alma frugum parens significantly recalls two solemn invocations of female divinities or personifications in Vergil’s Georgics, combining alma Ceres in the initial list of gods called upon (G.1.7) with the address to Italy as magna parens frugum (G.2.173). Two famous addresses in Vergil are thus laid under specific contribution in this resonant Apuleian context, with Lucius/ass amusingly producing highly literary and persuasive rhetoric : could Isis resist such an educated invocation from an ass ?. This rhetoric is reinforced as in the other prayers by further poeticisms, in suboles, circumfluus and femineus, 40 as well as ambages, aerumna and exanclare. 41 Isis’ reply to Lucius’ prayer, identifying herself, is equally lofty in expression (11.5) : 40 See respectively Brown (1987 : 336) on Lucr.4.1232 and Laurand (1936-8) 93, Wijsman (1996: 215) on Valerius Flaccus 5.442 and TLL 6.465.15ff (first in Cicero poet. and Vergil). 41 For ambages (first at Aeneid 6.29) cf. TLL 1.1833.66ff, for aerumna (Ennius Ann.45,60 Sk) cf. TLL 1.1066.47ff, for exanclare see n.34 above. 10 ‘En adsum tuis commota, Luci, precibus, rerum naturae parens, elementorum omnium domina, saeculorum progenies initialis, summa numinum, regina manium, prima caelitum, deorum dearumque facies uniformis, quae caeli luminosa culmina, maris salubria flamina, inferum deplorata silentia nutibus meis dispenso: cuius numen unicum multiformi specie, ritu vario, nomine multiiugo totus veneratus orbis. Inde primigenii Phryges Pessinuntiam deum matrem, hinc autochthones Attici Cecropeiam Minervam, illinc fluctuantes Cyprii Paphiam Venerem, Cretes sagittiferi Dictynnam Dianam, Siculi trilingues Stygiam Proserpinam, Eleusinii vetusti Actaeam Cererem, Iunonem alii, Bellonam alii, Hecatam isti, Rhamnusiam illi, et qui nascentis dei Solis inlustrantur radiis Aethiopes utrique priscaque doctrina pollentes Aegyptii caerimoniis me propriis percolentes appellant vero nomine reginam Isidem.’ Rerum naturae parens is paralleled in another description of a goddess in the anonymous iambic Precatio Terrae Matris, likely to be post –Apuleian (Anth.Lat.4.1 R./5.1 SB dea sancta Tellus, rerum naturae parens), 42 but in pre-Apuleian texts it is also difficult to avoid a connection with the Venus of the proem of Lucretius DRN 1, greeted as Aeneadum genetrix (1.1) and said to rule rerum natura (1.21), not the only allusion to this poetic proem in the Met. 43 The appropriation of Lucretius’ (metaphorical?) ruler of the universe is interesting here. On the one hand, it could be seen as an attempt to enlist Epicurean ideas of divinity as seen through the peculiar lens of Lucretius to contribute to Isis’ universal majesty. On the other hand, for the reader of Books 1-10, this literary link of Isis with Venus is internally significant within the plot of the novel and creates a nicely discordant note. Isis here claims to encompass all the female divinities to be found in the Met. : thus Ceres and Juno are picked up as a juxtaposed pair from the beginning of Book 6, and Venus must similarly recall the Venus of the inserted tale of Cupid and Psyche, who was so unflatteringly described as vain, capricious and cruel and as radically nonEpicurean.As often, the reader is offered different possible interpretations through this literary allusion : is Isis in encompassing Venus laying claim to the universal and dignified goddess of Lucretius’ proem, or to the Homerically anthropomorphic and unpleasant goddess of the novel’s own central section ? 42 43 These lines are plausibly dated to the 3rd century by Norden (1966 : 239). Cf. e.g. Harrison (1998 : 65). 11 Once again this specific intertextual allusion is supported by generally poetic language. Progenies has an archaic and poetic flavour, appearing in Ennius, Catullus, and Lucretius as well as Vergil, 44 while caeles is a standard poetic term for gods since Ennius (Trag.171,270 Jocelyn). Once again poetic plurals are in evidence : culmina caeli is from Manilius (1.150), and the plurals culmina, flamina and silentia are all common in poetic usage for their metrical convenience. 45 Poetic compound epithets also reappear : primigenius (in the variant form primigenus) is found in Lucretius (2.1106), sagittifer in Catullus, Vergil and Ovid. 46 Learned geographical epithets and proper names are another poetic type here : Dictynna goes back to Cinna (fr.14 Courtney) and is used by Tibullus (1.4.25) and Ovid (Met.2.441, Fast.6.755), and Stygius, Actaeus and Rhamnusia (= Nemesis) are also primarily poetic, 47 though we should recall that Actaeam here is a conjecture by Robertson based on a poetic passage (Statius Silv.4.8.50 Actaea Ceres) 48 and note the danger of circular argument here. One unique geographical term here may in fact have been corrupted in transmission from a poetic source. This is Cecropeiam. All the three other preApuleian passages (all poetic) which give this title of Minerva present the form Cecropius, usable in hexameters ( cf. Lucan 3.306 orant Cecropiae praelata fronde Mineruae Si quis Cecropiae madidus Latiaeque Minervae, 7.32.3 Te pia Cecropiae comitatur turba Minervae). Given that F (the sole authoritative MS) here garbles several of the other geographical epithets (pessinumtam, phlaphiam, raanusiam), that the Greek form is (e.g. Euripides Ion 636), and that in the context close euphony is intended with the ending of Paphiam, I would here print Cecropiam, thus restoring a standard poetic epithet. My final passage is Lucius’ prayer of thanks to Isis after his first initiation (11.25) : 44 Cf. Harrison (1991 : 66) on Aeneid 10.30. Culmina occurs six times in the Aeneid, all in the fifth foot of the hexameter, flamina twice each in Lucretius and Vergil in the same position; for silentia cf. Harrison (1991 : 75) on Aeneid 10.62-3. 46 Catullus 11.6, Vergil Aen. 8.725, Ovid Met.1.468. 47 Stygius : Vergil G.3.551, Aen.5.855, Tibullus 1.10.36, Horace Odes 2.20.8. Actaeus : Vergil Ecl.2.24, Ovid Met.2.554, Seneca Phaed.900. Rhamnusia (virgo) = Nemesis : Catullus 66.71, 68.77, Ovid Met.3.406. 48 The MSS read Eleusinii vetustam; Robertson’s conjecture vetust<i Actae>am attractively restores complete isocolon with the two preceding clauses. 45 12 Te superi colunt, observant inferi, tu rotas orbem, luminas solem, regis mundum, calcas tartarum. Tibi respondent sidera, redeunt tempora, gaudent numina, serviunt elementa. Tuo nutu spirant flamina, nutriunt nubila, germinant semina, crescunt germina. Tuam maiestatem perhorrescunt aves caelo meantes, ferae montibus errantes, serpentes solo latentes, beluae ponto natantes. At ego referendis laudibus tuis exilis ingenio et adhibendis sacrificiis tenuis patrimonio; nec mihi vocis ubertas ad dicenda, quae de tua maiestate sentio, sufficit nec ora mille linguaeque totidem vel indefessi sermonis aeterna series. Here we find a density of poetic features once more, both large and small. Spirant flamina (for flamina see n.45 above) comes from a prominent previous poetic address to a patron goddess, Ovid’s request to Venus to speed the poetical ship of the Fasti (4.18) : dum licet et spirant flamina, navis eat, naturally appropriate since Isis herself has claimed identity with Venus in 11.5 (above, Paphiam Venerem). Meare is a ‘vox poetarum altiorisque stili’ found from the time of Naevius (TLL 8.786.8ff), while pontus is also decidedly poetic. 49 On a larger scale, the phrase nec mihi vocis … aeterna series alludes to a long tradition of hyperbolic expressions for the poet’s incapacity to express something large-scale or important, 50 beginning from Iliad 2.488-90: Homer’s ten tongues and ten mouths, imitated by Ennius (Ann.468-9 Sk.), are upgraded to one hundred each by the time of Vergil (G.2.43-4 and Aen.6.625-6) non, mihi si linguae centum sint oraque centum, / ferrea vox, but the Apuleian passage seems to be the first to inflate the figure to one thousand, again an appropriate adaptation of an epic model to an ecstatic expression of religious feeling on Lucius’ part. More subversive readers might see this as showing Lucius’ continuing gullibility and autosuggestive hyperenthusiasm in his career as an initiate in Book 11. 51 49 See Tränkle (1960 : 40). Cf. Skutsch (1985 : 628-9). 51 For a reading along these lines see Harrison (2000) 235-52. 50 13 4 : The values of poetic language in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses At the beginning of the twenty-first century, we may at last have stopped thinking of Apuleius as a quirky late writer whose large-scale deployment of poetic language is a sign of his cultural decadence, and started viewing the poetic element in his novel as a positive feature, indeed as one which represents a central aspect of the whole literary culture of the high Roman empire. Here in conclusion I shall look at three ways in which the poetic language of the Met. is important : the general literary orientation of the novel which can be deduced from some of its poetical elements, the relation of such an overall literary stance to Apuleius’ own cultural context, and the place of these poetical elements in the history of Latin prose and poetry generally. First, the aspect of particular poetic intertextuality in the novel. As already noted in section 3, one key element in such research is that of the parallels and differences between Apuleius and the epic tradition : the ways in which the Metamorphoses reprocesses and remodels epic episodes and expressions (most notably perhaps the katabasis of Psyche in Met.6, clearly reworking Aeneas’ descent to the Underworld in Aeneid 6) 52 has led to significant conclusions about the novel’s para-epic status, how it plays on its relationship with the most prestigious literary genre both in order to display its prestigious literary learning (an element to which we will return) and in order to show its difference from the epic as a lower genre, primarily interested in entertaining the reader.53 This is only one of a number of similar strategies of allusion: for example, allusions to the neoteric and elegiac poetic traditions in the love-story of Cupid and Psyche, recently emphasised, 54 make clear the affinity of that part of Apuleius’ novel with traditional modes of erotic discourse in Latin poetry, and I have argued in section 3 above that poetic allusion can be used to create genuinely grand effects in elevated and intense scenes where human characters interact with divinities. New research on the interaction of Apuleius’ novel with Roman comedy, often rightly seen by writers on Apuleian style as a fashionable and convenient quarry for archaic and colloquial expressions in Apuleius, likewise suggests that important elements of shaping in the plot are drawn from this genre, for 52 See Finkelpearl (1990/1999) and the forthcoming Groningen commentary on this section of the novel (Zimmerman et al : 2003). 53 See on this e.g. Harrison (1997). 54 Cf. Mattiacci (1998). 14 example the New Comedy-type frame of the Cupid and Psyche story (a young man gets a girl into trouble but the two are reunited after separation and parental opposition in a final wedding). 55 All these investigations highlight several important contributions which poetic allusion can make to Apuleian literary interpretation. First, such allusions often indicate and promote a poetic genre crucial for understanding the literary tone of particular parts of the Met.; in each case we are dealing not just with appropriation of poetical vocabulary and structures, but also with the adaptation in a particular context of a genre’s ideology and attitudes, sometimes suitably reprocessed to fit their new framework of prose fiction. Second, the mixture of genres which the Met. clearly contains stresses the role of the ancient novel as a flexible and diverse genre, and thus as parallel to the modern novel; here the work of Bakhtin, currently highly fashionable amongst interpreters of the ancient novel, has much to say on the combination of different levels of language in the same work and on the novel as the ultimately open literary form.56 Thirdly, and perhaps most significantly, such poetic allusions tend to cluster at the more heightened parts of the novel. Poetic allusion is a rhetorical strategy deployed at crucial moments in the plot of the Met. to engage the attention of its intended learned readers. This brings me to the second of my three themes, the aspect of Apuleius’ own literary context. The display in the Met. of knowledge of a wide range of poetic genres which I have just suggested, though typical of the learned intertextuality of the most complex and interesting Latin literature of any period, seems particularly apt for the cultural context of Latin literature in the second century AD. Quite apart from the fashionable archaism implicit in the use of material from early poets such as Plautus and others, in the Met. as in Apuleius’ other work we are dealing with a writer who is strongly concerned to demonstrate in his literary performances his personal mastery of the historic resources of Latin literature, or, in Bourdieu’s terms, to show off his cultural capital, acquired at some expense and trouble through elite education and rhetorical training.57 The poets were the basis of all literary training; in the famous syllabuses given by Quintilian (10.1.46-131) for the reading of Latin and Greek literature by the aspiring orator, Roman prose (with praise of Cicero and 55 Cf. May (2002). See e.g. Finkelpearl (1998 : 18), and Harrison (2002) 167; for Bakhtin’s own work on the ancient novel see Bakhtin (1981) 3-83. 57 Cf. Bourdieu (1984), esp. 53-4. 56 15 disparagement of Seneca) naturally takes most space (more than one-third, 101-130), but of the remaining two-thirds much more than half (46-72, 85-100) is concerned with the Greek and Latin poets. The Met., therefore, can be said to use extensive poetic allusion to display the socio-cultural status of its author as one who has experienced and drawn from the classic elite literary education. This would be the case for any learned writer, but as I have tried to argue elsewhere, 58 this aspect of self-promotion and self-display is particularly appropriate to the second century AD, and makes Apuleius clearly parallel to the contemporary Greek sophists, whose similar epideictic self-representation and proclaimed mastery of Hellenic literary culture is such a striking feature of the Greek texts of the high Roman empire, what we call the Second Sophistic. 59 Finally, I turn to the place of poetic elements in the history of Latin prose in general and the light which Apuleius’ Met. can throw on this. Apuleius’ style in the heightened parts of the novel with its characteristically extensive use of tricolon, iscolon, chiasmus, verbal patterning and euphonic devices of all kinds has been rightly termed the climax of Roman Asianism in prose style. 60 Many of these features, especially the euphonic ones, are also clearly features of poetry, and in the phonic as well as the lexical aspects of the Apuleian high style we find (as Callebat argued) the merging of the codes of poetry and prose. 61 This is of particular interest in the context of the second century CE. For here in both Latin and Greek literary historians are clear that prose occupies the primary literary space previously taken by the major verse genres, even given the disappearance of most of the evidence in terms of the non-survival of most of the literary texts. After Juvenal it is hard to find verse texts of major size and substantial interest, in particular in the form of the epic; in some ways the novel (i.e. Apuleius) becomes the substitute for the epic in this period, 62 consistent with the intertextual relationship we have seen above between the Met. and its epic predecessors. The same is true in Greek; the artistic prose of the Second Sophistic, with which Apuleius’ high style is to be generally compared, is produced in a literary context remarkably bare of substantial poetic texts, and it is a truism of modern critical writing on the 58 Harrison (2000) Cf. esp. Schmitz (1997). 60 Cf. Norden (1898 : 596), Kenney (1990 : 30). 61 See n.20 above. 62 Cf. e.g. Steinmetz (1982 : 376-7), Conte (1994 : 588). 59 16 period that the literary energy of verse is transmuted into artistic prose such as that of Aelius Aristides or Longus.63 The traditional prejudices against Apuleian appropriation of poetic elements in the heightened parts of the Met. should be discounted in favour of a more positive approach. Detailed, contextualised and creative analysis of interaction with verse genres in the novel has many critical benefits, both in helping to define the literary character of the novel itself, and also in setting the novel in its literary context as a sophistic product in Latin and as a characteristic text of the second century CE, when prose generally absorbed and took on the literary role of poetry. 63 Cf. e.g. Reardon (1971 : 145), Whitmarsh (2001 : 27). 17 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bakhtin, M. (1981), The Dialogic Imagination (Austin). Baxter, R.T.S. (1971), ‘Tacitus’ use of Virgil in Book 3 of the Histories’, CPh 66 : 93-107. Baxter, R.T.S. (1972), ‘Tacitus’ use of Virgil in Books 1 and 2 of the Annals’, CPh 67 : 24669. Bernhard, M. (1927), Der Stil des Apuleius von Madaura (Stuttgart). Bourdieu, P. (1984), Distinction: a social critique of the theory of taste (London).. Bowie, E.L. (1989), 'Greek sophists and Greek poetry in the Second Sophistic', ANRW II.33.1 : 209-58. Brock, M.D. (1911), Studies in Fronto and His Age (Cambridge). Brown, R.D. (1987), Lucretius on Love and Sex (Leiden). Callebat, L. (1968), Sermo Cotidianus dans les Métamorphoses d'Apulée (Caen). Callebat, L. (1984), 'La prose d'Apulée dans le De Magia', WS 18 : 143-67 [reprinted in Callebat 1998] Callebat, L. (1994), ‘Formes et expressions dans les Métamorphoses d'Apulée’,ANRW II.34.2: 1616-64 [reprinted in Callebat 1998]. Callebat, L. (1998), Langages du roman latin (Spudasmata 71) (Hildesheim). Conte, G.B. (1994), Latin Literature : A History (Baltimore). Connors, C. (1998), Petronius The Poet (Cambridge). Facchini Tosi, C. (1986), ‘Forma e suono in Apuleio’, Vichiana 15 : 89-168. Finkelpearl, E. (1990), 'Psyche, Aeneas and an Ass: Apuleius Met. 6.10-6.21', TAPA 120: 333-48 [reprinted in Harrison, ed., 1999]. Finkelpearl, E. (1998), Metamorphosis of Language in Apuleius (Ann Arbor). Harrison, S.J. (1990) ‘Some Odyssean Scenes in Apuleius 'Metamorphoses'’, MD 25: 193201. Harrison, S.J. (1991), Vergil : Aeneid 10 (Oxford). Harrison, S.J. (1997), 'From Epic to Novel : Apuleius as Reader of Vergil', MD 39 : 53-74. Harrison, S.J. (1998), 'Some Epic Structures in Cupid and Psyche', in Zimmerman et al. (1998), 51-68. Harrison, S.J. (ed.) (1999), Oxford Readings in the Roman Novel (Oxford). Harrison, S.J. (2000), Apuleius: A Latin Sophist (Oxford). Harrison, S.J. (2002), ‘Constructing Apuleius : The Emergence of a Literary Artist’, Ancient Narrative 2 : 143-71 18 Hijmans, B. L. jr. and van den Paardt, R. Th. (edd). (1978), Aspects of Apuleius’ Golden Ass (Groningen). Hijmans Jr. B.L et. al. (1995), Apuleius Madaurensis Metamorphoses Book IX (Groningen). Hinds, S.E. (1998), Allusion and Intertext (Cambridge). Hunter, R.L. (1983), A Study of Daphnis and Chloe (Cambridge). Kenney, E.J. (1990), Apuleius: Cupid & Psyche (Cambridge). Keulen, W.H. (2003), Apuleius Madaurensis Metamorphoses Book I, 1-20 (Ph.D dissertation, Groningen). Laurand, L. (1936-8), Etudes sur le style des discours de Cicéron (Paris). Löfstedt, E. (1959), Late Latin (London) Marache, R. (1952), La critique littéraire de langue latine et le développement du goût archaïsant au IIe siècle de notre ère (Rennes). Mattiacci, S. (1993), ‘La lecti invocatio di Aristomene : pluralit di modelli e parodia in Apul.Met.1.16’, Maia 45 : 257-67. Mattiacci, S. (1998), ‘Neoteric and Elegiac Echoes in the Tale of Cupid and Psyche by Apuleius’, in Zimmerman et al. (1998), 151-64. May, R. (2002), A Comic Novel? Roman and New Comedy in Apuleius' Metamorphoses. (D.Phil Thesis, Oxford). Mayer, R.G. (2001), Tacitus : Dialogus de Oratoribus (Cambridge). Médan, P. (1925), La latinité d’Apulée dans les Métamorphoses (Paris). Miller, N.P. (1961-2), ‘Vergil and Tacitus’, PVS 1 : 25-34. Miller, N.P. (1986), ‘Vergil and Tacitus again’, PVS 18 : 87-108. Moreschini, C. (1994), Il mito di Amore e Psiche in Apuleio (Naples). Norden, E. (1898) Die Antike Kunstprosa vom VI. Jahrhundert v.Chr. bis in die Zeit der Renaissance [2 vols] (Leipzig). Norden, E. (1966), Kleine Schriften (Berlin). Pasetti, L. (1999), ‘La morfologia della preghiera nelle Metamorfosi di Apuleio’, Eikasmos 10 : 247-271. Petersmann, H. (1998), ‘Gab es ein Afrikanischen Latein? Neue Sichten eines alten Problems der lateinischen Sprachwissenschaft’, in: B.García Herńandez (ed.) (1998), Estudios de linguística latina, I.25–36 (Madrid). Reardon, B.P. (1971), Courants littéraires grècques des IIe et IIIe siècles après J.-C. (Paris). Roberts, M. (1989), The Jeweled Style : Poetry and Poetics in Late Antiquity (Ithaca). 19 Schmitz, T. (1997), Bildung und Macht: zur sozialen und politischen Funktion der zweiten Sophistik in der griechischen Welt der Kaiserzeit (Zetemata 97) (Munich). Skutsch, O. (1985), The Annals of Quintus Ennius (Oxford). Steinmetz, P. (1982), Untersuchungen zur römischen Literatur des zweiten Jahrhunderts nach Christi Geburt (Palingenesia 16) (Wiesbaden).. Tränkle, H. (1960), Die Sprachkunst des Properz und die Tradition der lateinischen Dichtersprache (Hermes Einz.15) (Wiesbaden). van Mal-Maeder, D. (2001), Apuleius Madaurensis Metamorphoses Livre II (Groningen). Walsh, P.G. (1970), The Roman Novel (Cambridge). Whitmarsh, T. (2001), Greek Literature and the Roman Empire (Oxford). Wijsman, H.J.W. (1996), Valerius Flaccus Argonautica Book V : A Commentary (Leiden). Zimmerman, M., et al. (edd.) (1998), Aspects of Apuleius’ Golden Ass II: Cupid and Psyche (Groningen). Zimmerman, M. (2000), Apuleius Madaurensis Metamorphoses Book X (Groningen). Zimmerman, M., et al. (2003) Apuleius Madaurensis Metamorphoses : Cupid and Psyche (Groningen).