A Brief History of Japan

advertisement

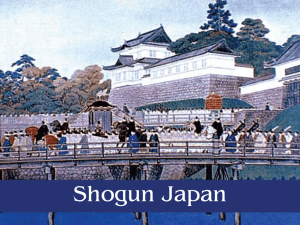

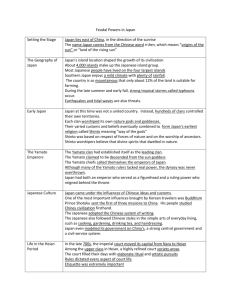

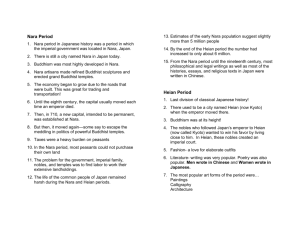

A Brief History of Japan Japan is an island. That fact has been important to its history. China first made an official visit to Japan in the 200s. The visitors dubbed Japan the Land of Wa, or harmony; according to the written records, at this time Japan was ruled by a shamaness named Himiko. Ancient Japan had its own mythology, oral histories which were collected into an official history of the land called the Kojiki in the year 712. The Kojiki tells us that the rulers of Japan are descended from the Sun Goddess Amaterasu Omikami through her grandson Jimmu, the first emperor of Japan. It is likely that the Kojiki was created for the purpose of establishing the dominant clan as the legitimate and god-given rulers of Japan. Other clans, or uji, gradually lost power and become subordinate to this ruling clan. The time of Jimmu and his descendants is called the Yamato Period. Keyhole tombs and Haniwa (clay burial figures) date from this period. The first historically documented period of Japanese history is the Nara period (712-793). It dates from the transfer of the capital to Nara. The new capital was based on the ideal Chinese city of Chang-An. The creation of the capital at Nara reflected a growing desire for centralized government and the stability it could bring. Steps had already been taken toward this end through the Taika Reforms of the mid 600s, which diminished the power of the uji (clans), and developed a central administration. The reforms show Continental influences such as Buddhism, popularized by Prince Shotoku in the late 500s. Todaiji was one of the first great temples in Nara. It is the largest totally wooden structure in the world. Todaiji The transfer of the Japanese capital from Nara west to Kyoto by Emperor Kammu marked the end of the Nara Period and the beginning of the Heian Period (794-1186). The Heian Period was a golden age dominated by the customs and tastes of the royal court in Kyoto. Court society developed definite styles of dress, music, and literature. Literature, in particular, flowered, and women authors were active. Murasaki Shikibu, a woman of the court, wrote the epic Tale of Genji, commonly acknowledged as the world’s first novel. Sei Shonagon, another court lady and Murasaki’s rival, wrote the Pillow Book, a collection of essays and observations on life and manners. These women wrote in hiragana, a slender, flowing script developed from simplified Chinese characters that later became the Japanese alphabet. Such writing was called onna-de, “woman’s hand.” Overall, the Heian period is associated with a refined, feminine aesthetic called Taoyame-buri (literally, “like a gentle woman”), whereas the Nara Period is characterized by more a more manly and vigorous aesthetic, “masura-o buri.” Heian Woman’s Costume During the Heian Period there was much commerce between Japan and the Continent. The Japanese monks Saicho and Kukai traveled to China to learn more about Buddhism, and when they returned they founded the Tendai and Shingon sects of Buddhism. The Tendai sect was based at Enryaku Temple on Mt. Hiei, which rises above Kyoto to the east. Tendai disciples believed in a life of service and the importance of the Lotus Sutra. The Shingon sect was based at Mt. Koya, a temple south of the capital. Shingon believers accepted Dainichi as the main incarnation of Buddha; this religion includes secret mantras (chants) and hand gestures. Pure Land Buddhism was also born in Heian times. It was popularized by the monk Genshin. Pure Landers believed in Tariki (salvation through another), vs. Jiriki (salvation through personal effort). They also emphasized chanting the nenbutsu, or evoking the name of Amida Buddha. The Byodoin, a temple near Kyoto devoted to Amida Buddha, was built at this time. Byodoin The Taira, or Fujiwara, clan dominated the court during the Heian Period, ruling behind the scenes through an extensive system of connections through marriage to the imperial family. The Fujiwara also made use of regencies. When a regent conducted matters of state on behalf of a child emperor that regent was called sessho. A kampaku was a regent for an adult emperor. This is an example of a situation occurring frequently throughout Japanese history in which the emperor held only nominal power, while the actual power resided elsewhere. The greatest of the Fujiwara family was Fujiwara no Michinaga (9661028), on whom Murasaki Shikibu based her dashing hero and lover, Genji. Modern actors dressed as Genji and his lover, Murasaki The Heian Period came to an end as court culture fell into a decline. The Heian aristocrats compromised their position by depending on warrior clans to quell rebellion and unrest in the provinces. The strength of provincial lords who owned shoen (manors) increased, and the central government weakened. Supported by country bushi (warriors), Minamoto Yoriyoshi and Yoriie consolidated the strength of the powerful Minamoto clan in the provinces. Although the Minamoto (Genji) clan ostensibly served the Taira (Fujiwara) clan, they had become strong enough to seize power themselves. Kiyomori, one of the last strong Taira (Fujiwara) leaders, had many of the Minamoto clan executed, but the family rallied around Minamoto Yoritomo in the East. Yoritomo’s younger brother Yoshitsune achieved a series of victories over the Taira clan, driving them from the capital and forcing them to flee ever south and west. The Fujiwara were finally defeated in the battle of Dan no Ura in 1185, where the seven year old emperor Antoku perished when his grandmother jumped with him into the waves. This battle marked the end of the Heian Period and the beginning of the Kamakura Period (1186-1336). The Battle of Dan no Ura Thus began the age of the shogun and the shogunate, or bakufu. Although the emperors retained their ceremonial title, during this period the de-facto ruler of Japan was the shogun, or general, who ruled from the eastern city of Kamakura. The culture of aristocrats withered away and a culture of warriors was born. In the late 1100s and early 1200s Zen Buddhism was brought over from China by the monks Eisai and Enni. Zen emphasized satori, or sudden enlightenment, instead of the reciting of sutras. Japan’s warrior class accepted Zen and refined its practice to a high art. Practicing Za-zen The Muramachi Period began in 1392 and continued until 1573. This period saw great unrest; the shogunate became less powerful and there was much warring in the provinces. At the same time there was steady economic development and Japan saw a rise of the merchant class. Eventually three figures arose from the chaos to reunify Japan under one government. Those men were Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Oda Nobunaga Toyotomi Hideyoshi Tokugawa Ieyasu The process of reunification began in 1598, when the daimyo (provincial lord) Oda Nobunaga managed to take Kyoto. His retainer and successor was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man of military genius and political vision. Toyotomi instituted new laws and reforms; he surveyed the land, disarmed villagers of their weapons to keep law and order, and attempted to expand the Japanese empire through an unsuccessful attack of Korea. He was also an important patron of the arts. It was partly through his sponsorship that the tea ceremony, created by Sen no Rikyu in the Azuchi Momoyama Period, was popularized and refined. Toyotomi had a tea room made for himself covered in gold leaf. A Reconstruction of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Tea Room During this time noh (traditional Japanese drama) also flourished under the patronage of Toyotomi and the warrior class. He ruled as kampaku (regent), as had Oda. On his death the various lords vied for power, but Tokugawa established his dominance in a great battle at Sekigahara in 1600 and became shogun. Noh mask Tokugawa’s unification of Japan marked the beginning of the period known as the Tokugawa Period or the Edo Period. Tokugawa moved the capital of Japan to Edo, a city that had originally been a small fishing village in eastern Honshu. He established a centralized feudal state in which the shogun controlled the daimyo (provincial lords) with an iron hand. Frustrated with the activities of Christian missionaries, Tokugawa closed Japan to the outside world, permitting no foreigners to set foot in the country excepting through the port of Nagasaki, where Dutch ships would come to trade. During this period the merchant class developed further, gaining both financial power and cultural dominance. Literature of this period reflected the life of merchants in major towns such as Edo and Osaka. The pleasure quarters, where wealthy men could be entertained by geisha of various ranks, became a popular subject of books and prints. A Woman of the Pleasure Quarters Under the Tokugawa clan’s rule Japan experienced two hundred years of stability and isolation from the rest of the world. This state continued until the arrival of Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships” from America in 1853. Through persuasion and the show of force, Perry succeeded in opening Japan to trade, which in turn resulted in a deluge of foreign culture and customs.