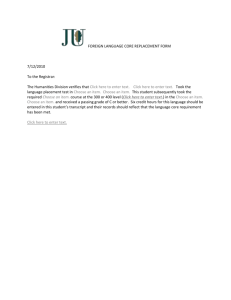

transcripts necessary for trial prep

advertisement

A motion for a continuance is addressed to the sound discretion of the trial court, and the trial court’s ruling will not be disturbed absent an abuse of discretion. People v. Hampton, 758 P.2d 1344, 1353 (Colo. 1988); see People v. Bakari, 780 P.2d 1089, 1092 (Colo. 1989). A trial court abuses its discretion when its ruling is manifestly arbitrary, unreasonable, or unfair. People v. Ellis, 148 P.3d 205, 211 (Colo. App. 2006). “‘To say that a court has discretion in resolving [an] issue means that it has the power to choose between two or more courses of action and is therefore not bound in all cases to select one over the other.’” People v. Crow, 789 P.2d 1104, 1106 (Colo. 1990)(quoting People v. Milton, 732 P.2d 1199, 1207 (Colo. 1987)). “There are no mechanical tests for determining whether the denial of a continuance constitutes an abuse of discretion. ‘The answer must be found in the circumstances present in every case, particularly in the reasons presented to the trial judge at the time the request is denied.’” Hampton, 758 P.2d at 1353-54 (quoting Ungar v. Sarafite, 376 U.S. 575, 589, 84 S.Ct. 841, 850, 11 L.Ed.2d 921 (1964)). In addition to an abuse of discretion, a defendant must also demonstrate actual prejudice arising from denial of the continuance. People v. Denton, 757 P.2d 637, 638 (Colo. App. 1988). In United States v. Fountain, 642 F.2d 1083, 1087 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 451 U.S. 993, 101 S.Ct. 2335, 68 L.Ed.2d 854 (1981), the court noted that "advance planning is in the best interest of the parties and of the judicial system.... Trial by ambush may produce good anecdotes for lawyers to exchange at bar conventions, but tends to be counterproductive in terms of judicial economy." (Citations omitted.) The Fourteenth Amendment imposes upon the state the obligation to provide an indigent defendant with those basic instruments and services essential to his or her right to adequately defend against a criminal charge. See Britt v. North Carolina, 404 U.S. 226, 92 S.Ct. 431, 30 L.Ed.2d 400 (1971) (plurality opinion) (state must provide indigent defendant with a free transcript of former trial that ended in mistrial when defendant makes claim of need for transcript for second trial and no adequate substitute will meet defendant's trial preparation needs); Gardner v. California, 393 U.S. 367, 89 S.Ct. 580, 21 L.Ed.2d 601 (1967) (indigent prisoner entitled to free transcript of evidentiary hearing at habeas corpus proceeding in order to present new petition before higher state court when there was no adequate substitute for the transcript); Roberts, 389 U.S. 40, 88 S.Ct. 194 (indigent defendant entitled to free transcript of preliminary hearing for use at trial); Long v. Dist. Court of Iowa, 385 U.S. 192, 87 S.Ct. 362, 17 L.Ed.2d 290 (1966) (per curiam) (indigent defendant must be furnished free transcript of state habeas corpus proceeding for use on appeal). Eskridge v. Washington Prison Bd., 357 U.S. 214, 78 S.Ct. 1061, 2 L.Ed.2d 1269 (1958) (provision of trial transcript may not be conditioned on approval of judge); Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487, 83 S.Ct. 774, 9 L.Ed.2d 899 (1963) (same); Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477, 83 S.Ct. 768, 9 L.Ed.2d 892 (1963) (public defender's approval may not be required to obtain coram nobis transcript); Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305, 86 S.Ct. 1497, 16 L.Ed.2d 577 (1966) (unconstitutional to require reimbursement for cost of trial transcript only from unsuccessful imprisoned defendants); Long v. District Court of Iowa, 385 U.S. 192, 87 S.Ct. 362, 17 L.Ed.2d 290 (1966) (State must provide transcript of postconviction proceeding);Roberts v. LaVallee, 389 U.S. 40, 88 S.Ct. 194, 19 L.Ed.2d 41 (1967) (State must provide preliminary hearing transcript); Gardner v. California, 393 U.S. 367, 89 S.Ct. 580, 21 L.Ed.2d 601 (1969) (State must provide habeas corpus transcript); Williams v. Oklahoma City, 395 U.S. 458, 89 S.Ct. 1818, 23 L.Ed.2d 440 (1969) (State must provide transcript of petty-offense trial); Mayer v. Chicago, 404 U.S. 189, 92 S.Ct. 410, 30 L.Ed.2d 372 (1971) (State must provide transcript of nonfelony trial). The only cases that have rejected indigent defendants' claims to transcripts have done so either because an adequate alternative was available but not used, Britt v. North Carolina, 404 U.S. 226, 92 S.Ct. 431, 30 L.Ed.2d 400 (1971), or because the request was plainly frivolous and a prior opportunity to obtain a transcript was waived, United States v. MacCollom, 426 U.S. 317, 96 S.Ct. 2086, 48 L.Ed.2d 666 (1976). IN THE CONTEXT OF PRETRIAL MOTIONS TO SUPPRESS TRANSCRIPTS PRIOR TO TRIAL Pretrial hearings to suppress evidence are scheduled prior to the jury trial date in order to allow for a transcript to be prepared for use in the jury trial. This is a normal and customary procedure that has been allowed in virtually every courtroom, and is critical for effective impeachment purposes. Colorado Courts, and the Colorado Rules of Criminal Procedure, both indicate that motions should be heard before trial to allow both the defense and the prosecution an opportunity to understand the evidence that will be utilized in the trial. CRCP 41(e), (g); People v. Hastings, 983 P.2d 78, 83 (Colo. App. 1998); People v. Tyler, 874 P.2d 1037, 1039 (Colo. 1994). People v. Barela, 826 P.2d 1249, 1252-54 (Colo. 1992). Before considering whether the defendant's constitutional rights were violated by the county court's dismissal of the unsworn jury and the rescheduling of the trial, we address the propriety of the county court's practice of setting suppression motions for hearing after a jury has been impaneled but has not yet been sworn. We conclude that this practice, when adopted and followed as a routine scheduling device, undermines the general procedural scheme contemplated by the Colorado Rules of Criminal Procedure for resolving suppression motions and interlocutory appeals from suppression rulings. Crim.P. 41(e) provides that a motion to suppress evidence based on an alleged unconstitutional search and seizure "shall be made and heard before trial unless opportunity therefor did not exist or the defendant was not aware of the grounds for the motion, but the court, in its discretion, may entertain the motion at the trial." Crim.P. 41(g) contains a similar requirement with respect to a motion to suppress an alleged involuntary confession or admission made by the defendant. We have emphasized on more than one occasion the importance of filing and resolving suppression motions in advance of trial. E.g., People v. Voss, 191 Colo. 338, 340-41, 552 P.2d 1012, 1014 (1976); Morgan v. People, 166 Colo. 451, 45354, 444 P.2d 386, 387 (1968). The general requirement that suppression motions be made and heard prior to trial serves several purposes. The expeditious resolution of such motions in advance of jury selection provides both the prosecution and the defense an opportunity to resolve the constitutional admissibility of prosecutorial evidence that often will have a direct effect on trial strategy. In addition, pretrial suppression rulings permit the prosecution and the defense to give adequate consideration to the feasibility of pursuing a plea agreement prior to trial. The seasonable disposition of a case by plea agreement results in more effective use of court time and cuts down on the inconvenience and expense occasioned by last-minute dispositions after a jury panel has been assembled and witnesses have been subpoenaed. Finally, the timely pretrial resolution of suppression motions allows the prosecution a meaningful opportunity to assess the correctness of the suppression ruling and to file an interlocutory appeal from the ruling prior to the attachment of jeopardy. In a trial to a jury, jeopardy attaches when the jury is impaneled and sworn. Crist v. Bretz, 437 U.S. 28, 37-38, 98 S.Ct. 2156, 2161-62, 57 L.Ed.2d 24 (1978); Jeffrey v. District Court, 626 P.2d 631, 636 (Colo.1981). In a trial to the court, jeopardy attaches when the first witness is sworn. Serfass v. United States, 420 U.S. 377, 388, 95 S.Ct. 1055, 1062, 43 L.Ed.2d 265 (1975); Jeffrey, 626 P.2d at 636. Because the United States and Colorado Constitutions prohibit placing an accused twice in jeopardy for the same offense, U.S. Const.Amend. V; Colo. Const. art. II, § 18, it necessarily follows that the prosecution's "only meaningful avenue of appeal" from a suppression ruling must occur prior to the attachment of jeopardy. People v. Traubert, 199 Colo. 322, 330, 608 P.2d 342, 348 (1980). Crim.P. 41.2 is designed to provide the prosecution a "meaningful avenue of appeal" from a county court's suppression ruling by authorizing the prosecution to file a notice of appeal with the clerk of the county court and with the clerk of the district court "within five days after the adverse ruling in the county court." Crim.P. 41.2(b). [4] While the issue before us is whether the county court's practice of routinely hearing suppression motions after a jury is impaneled but not yet sworn for trial created the potential for abuse of the interlocutory appeal process, we are convinced from a review of the record that there was no prosecutorial abuse of the interlocutory appeal process in this case. The prosecution, as the district court determined, did no more than assert its right to take an interlocutory appeal from the county court's suppression ruling within the time frame established by Crim.P. 41.2. The dismissal of the unsworn jury and the rescheduling of the trial was not the product of prosecutorial bad faith but, rather, was the direct result of the county court's scheduling practice. The practice at issue was developed by the county court, and, even though instituted for the convenience of prosecution witnesses, it was utilized as a routine scheduling device for setting the county court's docket--a matter for which the county court, and not the prosecution, is ultimately responsible. To say that there was no prosecutorial abuse of the interlocutory appeal process in this case is not to imply that the county court's scheduling practice is without the potential for serious damage to the parties. On the contrary, we are of the view that the scheduling practice at issue here creates the potential for unnecessary postponements and delays that are inimical to the orderly procedural scheme contemplated by Crim.P. 41.2 for resolving suppression motions. When, for example, a trial court grants a suppression motion after jury selection but prior to swearing the jury, it places the prosecution in the awkward position of proceeding to trial with a much weaker case, requesting a continuance in order to file an interlocutory appeal, or attempting to settle the case by a weak plea-offer that might not otherwise be in the interest of justice. On the other hand, when a court denies a suppression motion after a jury has been impaneled but has not yet been sworn to try the case, it might well place the defendant in the position of either requesting a continuance in order to re-evaluate the case or hastily accepting a last minute plea offer which, had the suppression motion been resolved earlier, would have been more thoroughly considered. We accordingly disapprove the county court's practice of routinely scheduling suppression motions subsequent to jury selection but prior to the swearing of the jury for trial. While we disapprove of the practice employed by the county court, we point out that there may be exceptional circumstances that justify a trial court's scheduling of a suppression motion immediately prior to the attachment of jeopardy or even during the trial itself. The text of Crim.P. 41(e), which states that "the court, in its discretion, may entertain the motion at trial," contemplates that there may be special circumstances which warrant the departure from the general requirement of Crim.P. 41(e) that "[t]he motion shall be made and heard before trial unless opportunity therefor did not exist or the defendant was not aware of the grounds for the motion." These exceptional circumstances, for example, might include an extremely burdensome docket preclusive of a more timely hearing and resolution of the motion, the justifiable unavailability of witnesses or counsel for an earlier hearing date, the unavoidable continuance of a previously scheduled motion to the trial date, or other unforeseen circumstances. IN THE CONTEXT OF PRELIMINARY HEARING TRANSCRIPTS PRIOR TO TRIAL Gonzales v. District Court In and For Weld County, 198 Colo. 505, 602 P.2d 857, 858-59 (Colo. 1979) (footnotes omitted) A preliminary hearing transcript can be of great value to a defendant at trial. It is a "vital impeachment tool for use in crossexamination of the State's witnesses" and for trial preparation in general. [198 Colo. 507] Coleman v. Alabama, 399 U.S. 1, 9, 90 S.Ct. 1999, 2003, 26 L.Ed.2d 387, 397 (1969). See also Conley v. Dauer, 321 F.Supp. 723 (W.D.Pa.1970), remanded, 463 F.2d 63 (3d Cir.), Cert. denied, 409 U.S. 1049, 93 S.Ct. 521, 34 L.Ed.2d 501 (1972); Brooks v. Edwards, 396 F.Supp. 662 (W.D.N.C.1974); United States v. Acosta, 495 F.2d 60(10th Cir. 1974). As a practical matter, the transcript must be available to defense counsel prior to the trial if it is to be useful as an impeachment and trial preparation tool. Conley, supra ; United States ex rel. Wilson v. McMann, 408 F.2d 896 (2d Cir. 1969). The defendant's lawyer should not be forced to rely on his memory of the preliminary hearing, or notes prepared at the hearing, to establish inconsistencies between testimony at the hearing and at trial. United States ex rel. Wilson, supra ; Gardner v. California, 393 U.S. 367, 89 S.Ct. 580, 21 L.Ed.2d 601 (1968); Hardy v. United States, 375 U.S. 277, 288, 84 S.Ct. 424, 431, 11 L.Ed.2d 331, 339 (1964) (Goldberg, J., concurring). Providing the preliminary hearing transcript for the first time at trial is thus not an adequate alternative to providing the transcript before the trial. Acosta, supra ; Britt v. North Carolina, 404 U.S. 226, 92 S.Ct. 431, 30 L.Ed.2d 400 (1971). In the case before us, the respondent did not consider the value of the preliminary hearing transcript to the petitioner as a tool for trial preparation and impeachment of testimony at trial. The court also erred in determining that providing a transcript of the hearing at trial, should testimonial inconsistencies surface at that time, would be an adequate alternative to providing the transcript before the trial. These errors constituted an abuse of the court's discretion. The state must provide a transcript of a preliminary hearing at the request of an indigent defendant in a criminal case when the transcript is necessary for an effective defense. Britt, supra ; Roberts v. LaVallee, Warden, 389 U.S. 40, 88 S.Ct. 194, 19 L.Ed.2d 41 (1967). Recognizing the possible abuses that could result from our decision, our holding is limited to cases in which the defendant, because of his plea of not guilty, will actually proceed to trial and in which there is a reasonable assurance that testimony presented by prosecution witnesses at the preliminary hearing will also be presented at trial. People v. Nord, 790 P.2d 311, 316 (Colo. 1990) The value of a preliminary hearing transcript to the defense of a criminal case is self-evident. After remarking in Gonzales v. Dist. Court,198 Colo. 505, 602 P.2d 857 (1979), that the transcript not only enhances the defendant's ability to prepare an adequate defense but also may serve as a "vital impeachment tool for use in cross-examination of the State's witnesses," we went on to emphasize the importance of making the transcript available sufficiently in advance of the trial itself: As a practical matter, the transcript must be available to defense counsel prior to trial if it is to be useful as an impeachment and trial preparation tool.... The defendant's lawyer should not be forced to rely on his memory of the preliminary hearing, or notes prepared at the hearing, to establish inconsistencies between testimony at the hearing and at trial.... Providing the preliminary hearing transcript for the first time at trial is thus not an adequate alternative to providing the transcript before the trial. 198 Colo. at 507, 602 P.2d at 858. (Citations omitted). The same observations apply even more cogently to a pro se defendant. A trial court, therefore, should not require a defendant to make a showing of a particularized need for the transcript. Britt, 404 U.S. at 228, 92 S.Ct. at 434. [6] Unless the record irrefutably shows the contrary, the need for a preliminary hearing transcript, or some adequate alternative, is to be presumed. … At 318-19 Although some constitutional rights are so basic to a fair trial that their violation can never be considered harmless, e.g., Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335, 83 S.Ct. 792, 9 L.Ed.2d 799 (1963) (denial of counsel to indigent defendant charged with felony); Payne v. Arkansas, 356 U.S. 560, 78 S.Ct. 844, 2 L.Ed.2d 975 (1958) (admission of coerced confession in criminal trial); Tumey v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510,47 S.Ct. 437, 71 L.Ed. 749 (1927) (trial before judge having financial interest in result), the unconstitutional denial of an indigent defendant's request for a preliminary hearing transcript is not one of them. See, e.g., United States v. Rosales-Lopez, 617 F.2d 1349 (9th Cir.1980) (failure of trial court to provide indigent defendant with transcript of suppression hearing, although an error of constitutional dimension, was harmless where there were only two minor discrepancies between testimony at suppression hearing and trial testimony); United States ex rel. Moore v. Illinois, 577 F.2d 411 (7th Cir.1978) (although trial court erred in failing to provide indigent defendant with transcript of preliminary hearing at which an allegedly suggestive confrontation took place between defendant and rape victim, error was harmless), cert. denied, 440 U.S. 919, 99 S.Ct. 1242, 59 L.Ed.2d 471 (1979); see also United States ex rel. Cadogan v. LaVallee, 428 F.2d 165 (2nd Cir.1970) (failure to provide indigent defendant with transcript of suppression hearing not prejudicial where alleged discrepancies between suppression testimony and trial testimony were trivial and transcript would not have provided defendant with any significant assistance in defense of charge), cert. denied, 401 U.S. 914, 91 S.Ct. 887, 27 L.Ed.2d 813 (1971). A reviewing court, however, cannot characterize a constitutional error as harmless unless it is satisfied after a careful scrutiny of the entire record that the error was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. E.g., Satterwhite v. Texas, 486 U.S. 249, 108 S.Ct. 1792, 100 L.Ed.2d 284 (1988); Harrington v. California, 395 U.S. 250, 89 S.Ct. 1726, 23 L.Ed.2d 284 (1969); Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18, 87 S.Ct. 824, 17 L.Ed.2d 705 (1966); LeMasters v. People, 678 P.2d 538(Colo.1984); People v. Myrick, 638 P.2d 34 (Colo.1981). If there is a reasonable possibility that the constitutional error might have contributed to the conviction, the error cannot be viewed as harmless. E.g., Chapman, 386 U.S. 18, 87 S.Ct. 824. If, on the other hand, a review of the entire record discloses no such reasonable possibility, then the error properly may be deemed harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. E.g., Harrington, 395 U.S. 250, 89 S.Ct. 1726; LeMasters, 678 P.2d 538. Our review of the record, including the transcript of the preliminary hearing, satisfies us that the constitutional error in this case was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt FOOTNOTE 6 The defendants concede in their brief that when the request for a free transcript of former testimony is made as a delaying tactic, the request may properly be denied. E.g.,United States v. Smith, 605 F.2d 839 (5th Cir.1979). Harris v. District Court of City and County of Denver, 843 P.2d 1316, 1319-20 (Colo. 1993) In addition to providing judicially enforced safeguards to prevent unlawful detentions and unwarranted trials, a preliminary hearing provides a defendant several benefits which may be helpful at trial. In Coleman v. Alabama, 399 U.S. 1, 90 S.Ct. 1999, 26 L.Ed.2d 387 (1970), the Supreme Court recognized that the preliminary hearing provided by an Alabama statute afforded a defendant with opportunities to acquire a vital impeachment tool for subsequent use in cross-examining prosecution witnesses at trial, to preserve favorable testimony of witnesses who do not appear at the subsequent trial, and to discover the prosecution's case and thus to make possible the preparation of a proper defense. Id. at 9, 90 S.Ct. at 2003. These benefits are useless, however, in the absence of an accurate and complete transcript of essential portions of a preliminary hearing. We have previously emphasized the trial preparation benefits arising from preliminary hearings. In Gonzales v. District Court, 198 Colo. 505, 602 P.2d 857 (1979), we held that the state must provide a transcript of a preliminary hearing at the request of an indigent defendant in a case where the transcript is necessary for an effective defense. In Gonzales, the defendant, who was indigent and was charged with first degree murder, filed a motion requesting a transcript of the preliminary hearing at no cost. The district court granted the motion in part but denied the motion with respect to the testimony of three witnesses who had testified at the preliminary hearing. In an original proceeding we concluded that the district court abused its discretion in denying the defendant's request for a complete transcript of the preliminary hearing. Gonzales, 198 Colo. at 507, 602 P.2d at 858. In reaching that conclusion, we observed that a preliminary hearing transcript can be of great value to a defendant at trial for impeachment and other general trial preparation purposes. Id. at 506, 602 P.2d at 858. We also observed that a defense attorney should not at trial be forced to rely on the attorney's "memory of the preliminary hearing, or notes prepared at the hearing, to establish inconsistencies between testimony at the hearing and at trial." Id. at 507, 602 P.2d at 858. We limited our holding to cases in which the defendant would proceed to trial and in which there was a reasonable assurance that the prosecution witnesses who testified at the preliminary hearing would testify at trial. Id., 602 P.2d at 858-59. In People v. Nord, 790 P.2d 311 (Colo.1990), we again emphasized the importance of a transcript of a preliminary hearing for trial preparation purposes. We held in an appeal of a Colorado Court of Appeals judgment that in the circumstances of that case the district court's order denying the defendant's request for a free transcript of the preliminary hearing constituted harmless error. Id. at 319. In so doing, we compared the testimony presented at the preliminary hearing to the testimony presented at trial. Id. at 31819. We also noted that unless the record irrefutably demonstrates to the contrary, the need for a preliminary hearing transcript or some adequate alternative is to be presumed. Id. at 316. Gonzales and Nord emphasized the significance of the availability of a transcript of preliminary hearing proceedings for purposes of preparing for trial. Such hearings may not be converted into discovery proceedings simply because they assume importance for trial preparation purposes. However, because defendants in criminal cases are not able to take discovery depositions of prosecution witnesses, [3]and prosecution witnesses need not discuss their testimony in advance with defense counsel, the preliminary hearing takes on added significance in the total spectrum of criminal adjudication. Gonzales and Nord were decided in the context of cases wherein preliminary hearing transcripts were available. The unavailability of such a transcript due to technical transcription difficulties prevents a defendant from relying on the trial preparation benefits we recognized in those decisions. While additional expense and time will be consumed whenever a second preliminary hearing is required for any reason, the occasions on which such second hearings should be required as the result of technical transcription difficulties will no doubt be relatively few in number. In this case, the defendant asserts that the testimony presented at the preliminary hearing is directly relevant and of significance to his trial preparation, both for purposes of establishing his defense of self-defense and for purposes of impeaching or refuting the testimony of two eyewitnesses to the events that resulted in the victim's death. There is no suggestion in the record that the People will not rely at trial on testimony by those eyewitnesses or that the defendant will not proceed to trial. Furthermore, the record does not indicate that there is some alternative mode of reconstructing that testimony from the notes of the participating attorneys or the county court judge. See Medina v. District Court, 189 Colo. 516, 517, 543 P.2d 62, 63 (1975). In view of the totality of the circumstances here presented, we conclude that the district court's denial of the petitioner's motion for a second preliminary hearing constitutes an abuse of discretion. IN THE CONTEXT OF FIRST TRIAL TRANSCRIPTS BEFORE RETRIAL People v. Wells, 754 P.2d 420 (Colo.App. 1987) A transcript of a prior mistrial is not only a useful impeachment tool, but it is also a valuable aid in preparation for trial. See Britt v. North Carolina, 404 U.S. 226, 92 S.Ct. 431, 30 L.Ed.2d 400 (1971). However, in order to be a useful tool, the transcript must be available to defense counsel prior to trial. See Gonzales v. District Court, 198 Colo. 505, 602 P.2d 857 (1979). Counsel should not be forced to rely upon his memory of the prior mistrial or notes prepared during the proceeding. See Gonzales v. District Court, supra. Thus, the importance of a transcript is without question. See People v. St. John, 668 P.2d 988 (Colo.App.1983). Here, the trial court's failure to grant the continuance denied defendant the opportunity to prepare properly for trial. Identity was the sole issue at trial, and the People's case relied heavily upon the victim's identification testimony. Her recall of the encounter and her testimony regarding the People's evidence provided the basis of the prosecution. Therefore, under these circumstances, a transcript of the prior mistrial would have been a valuable preparation tool for the defendant. See Gonzales v. District Court, supra. The only reason for denying the continuance was the resulting delay necessary to prepare a transcript. But any delay was outweighed by the defendant's need for the transcript. See Britt v. North Carolina, supra; People v. St. John, supra. People v. Wells, 776 P.2d 386 (Colo. 1989) reversed, not because the logic was wrong but because the Supreme Court felt the record was inadequate to support the conclusion. At p. 389 The record on appeal contains neither the defendant's motion nor any transcript of any trial proceedings directed to consideration of the motion. The record contains no other evidence to support a conclusion that delay caused by the time necessary to prepare a transcript was the sole reason for the trial court's denial of the defendant's motion. The only reference in the record to the motion for continuance and for a transcript, other than a reference in the defendant's motion for judgment of acquittal or new trial filed July 18, 1985, after the conclusion of the second trial, is the trial court's minute order of July 5, 1985, which states, "DEF MOTN FOR TRANSCRIPT/AND CONT--DENIED." In this state of the record, an appellate court can only speculate as to the reasons for the trial court's decision. People v. St. John, 668 P.2d 988, 988-89 (Colo.App. 1983) Defendant principally contends the trial court erred when it refused to grant him a transcript of the trial testimony given by witness Magnall, a key prosecution witness during the first trial. The testimony of Magnall established many of the basic facts which led to the conviction of defendant, and tended to negate defendant's alibi defense. Defendant alleges that record would reveal five different instances in which this witness changed her story regarding these vital incidents as compared with her testimony during the second trial. With the transcript of the first trial, therefore, defendant could have impeached this witness at the second trial and the verdict of the jury might have been different. In Britt v. North Carolina, 404 U.S. 226, 92 S.Ct. 431, 30 L.Ed.2d 400 (1971) the Supreme Court stated: "[It] can ordinarily be assumed that a transcript of a prior mistrial would be valuable to the defendant in at least two ways: as a discovery device in preparation for trial, and as a tool at the trial itself for the impeachment of prosecution witnesses." The court further held that a state should provide indigent persons with the basic tools of an adequate defense when they are readily available. Here, the transcript could have been provided to defendant for a minimal cost and was vital to his defense. As a matter of equal protection, it should have been provided to him. Britt v. North Carolina, supra; see Gonzales v. District Court, 198 Colo. 505, 602 P.2d 857(1979). The State admits error in the refusal to provide the transcript, but it avers such error was harmless. Considering the critical nature of Magnall's testimony, and the alleged inconsistencies therein, we do not agree. This error was of such magnitude that it requires a new trial of this action, and we therefore reverse the judgment of the district court. Crim.P. 52(b); People v. Barker, 180 Colo. 28, 501 P.2d 1041 (1972); see also People v. Matthews, 662 P.2d 1108 (Colo.App.1983). On appeal, we review a trial court’s denial of a defendant’s request for free transcripts for an abuse of discretion. See Jurgevich v. Dist. Court, 907 P.2d 565, 568 (Colo. 1995). A trial court abuses its discretion only when its decision is manifestly arbitrary, unreasonable, or unfair. Id. Defendants who request free trial transcripts to prepare motions for collateral attack must demonstrate that they may be entitled to postconviction relief and that the record might contain specific facts that would substantiate alleged errors. Id. at 567.