The Australian Scholarship in Teaching Project

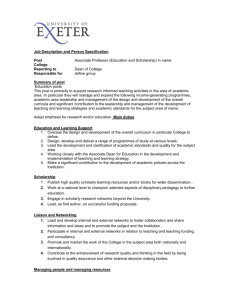

advertisement