AGQTP Final Report - Association of Independent Schools of NSW

advertisement

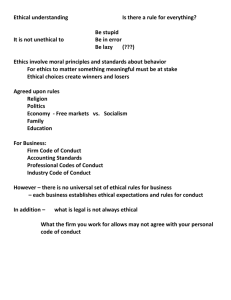

AGQTP FINAL REPORT 2011 PROJECT ACTIVITY AREA: School Name Pymble Ladies’ College Project Activity Area Pedagogy Project title Ethics Toolkit Contact person/s Maura Manning Contact number and email 9855 7799 mmanning@pymblelc.nsw.edu.au There is no restriction on the amount of space used to complete your AGQTP report. Please use as much space as required to give a detailed overview of your project. Section 1- For publication on www.aisnsw.edu.au/pd Project Summary a) Focus What was the project focus? The central focus was to encourage ethical thinking and ethical decision making in Year 9 students. By developing habits of ethical thinking, students will be more likely to adopt an ethical approach when faced with difficult (and mundane) decisions. Our hope was that by creating a shared language that can be used across core academic subjects and pastoral programs in Year 9, students will internalise the process and use it to make decisions outside of the classroom and school. We were also looking for a meaningful way to integrate the ethical behaviour general capability from the Australian Curriculum documents. We saw this mandate as an invitation to work in a cross-curricular team to devise a unified approach to this requirement. b) Successes and Impacts In what ways did your project meet the appropriate outcomes below All Project Activity Areas strengthen the currency and depth of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and skills Our project drew on a wide range of pedagogies and required participants to conduct research and reading into a number of areas. To some degree each of the following informed our project. 1 - Harvard/Project Zero Making Thinking Visible Harvard University’s Project Zero educational research group looks at ways to create communities of reflective, independent learners; to enhance deep understanding across disciplines and to encourage critical and creative thinking. As part of our school wide professional learning plan, individual teachers have been completing online courses offered by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Four of the teachers working on this project have completed the Making Thinking Visible course and another four have completed the Teaching for Understanding course. Visible Thinking is a research-based approach to integrating the development of students' thinking with content learning across subject matters through the use of systematic, generic thinking routines. The thinking routines guide students’ thought processes and encourage metacognition. We sought to emulate the Visible Thinking routines with our project by creating a generic routine that students and teachers could apply in different circumstances. “Thinking routines such as these provide the structures through which students collectively as well as individual initiate, explore, discuss, document, and manage their thinking in classrooms.” (Ritchhart, 2002) The project group experimented with the Visible Thinking routines in our classes and discussed what it is that makes these routines effective. We agreed that the common goal of helping student develop thinking dispositions that support thoughtful learning by making the processes of thinking explicit was key. (Ritchhart, 2006) Similarly, the idea that thinking routines are grounded in “an enculturative model of dispositional development which views thinking, and more specifically the disposition toward thinking, as something that must be nurtured in students over time” (Tishman, Perkins, & Jay, 1993 cited in Ritchhart, 2006) was key in the development of the Ethics Toolkit. We wanted to see our project become part of the fabric of the school. Throughout our project, we focused on the idea that any classroom routine is a practice crafted to achieve a specific end in an efficient workable manner. The success of the routine is dependent on teachers’ recognition of the practice as an effective tool for achieving the outcomes they desire. (Ritchhart, 2006) This idea guided our refinements of our project. Our research into what Visible Thinking is, our experimentation with the routines in our classrooms and our close examination of the routines to replicate the effective characteristics in our routine strengthened our pedagogical knowledge. - Costa’s Habits of Mind As with Visible Thinking in our early research, Art Costa’s Habits of Mind emerged as model similar in intent to our project. Costa and Kallick (2000) define a “Habit of Mind” as a “disposition toward behaving intelligently when confronted with problems,the answers to which are not immediately known. When humans experience dichotomies, are confused by dilemmas, or come face to face with uncertainties--our most effective actions require drawing forth certain patterns of intellectual behaviour. When we draw upon these intellectual resources, the results that are produced through are more powerful, of higher quality and greater significance than if we fail to employ those patterns of intellectual behaviours.” This thinking was in keeping with our intent for the Ethics Toolkit. 2 On further examination of Costa and Kallick’s work we came to see the importance of “cues” that signal students to undertake a particular type of thinking and the importance of “patterns” in our project. We also were interested in the idea that the success of our routine would depend on a certain level of skilfulness that would enable students to employ and carry through the ethical thinking behaviours effectively over time. (Costa and Kallick, 2000) This informed our belief that students need to be immersed in the thinking strategy across a range of subjects and contexts to ensure it became second nature to them. - Ethical decision making After examining the research underpinning thinking routines, we began to look explicitly at what ethical decision making models exist. Our research led us to the Institute for Global Ethics, an organisation that works with businesses and schools in the United States. They have developed an Ethical Literacy approach that looks at building school-wide ethical culture. Their model was much more comprehensive than what we were trying to do. In speaking to them, we determined that what we were proposing might sit inside their work, but would by no means replace it. Two of our team members participated in the training offered on Building Ethical School Culture. Similarly, we looked at The Values Exchange developed by David Seedhouse. This website provides a forum and a framework for students to debate social issues. It presents a sophisticated process through which students work to come to a well-informed stance on a particular issue. It steps out the metacognitive process of making an ethical decision, but it is dependent on a series of complex prompts. This system is very effective at broadening students’ thinking and encouraging logical reasoning, but it is much too complex to be second nature to the students as we had hoped the Ethics Toolkit would be. Teachers on the project team used the Values Exchange in Science, English and Commerce lessons and determined that the Values Exchange has a very important place in our programs, but did not replace the need for a simple and clear ethical thinking routine. Further to the research into Ethical Literacy and the Values Exchange, a team member attended a one-day seminar hosted by the St James Ethics Centre on ethical decision making. The workshop was pitched at adults who work in industries that face ethical dilemmas on a daily basis. The course attendees included doctors, lawyers, town planners and others. This day was a breakthrough for the work conducted by the Ethics Toolkit team because the workshop affirmed much of the work that we had already done. It was very heartening to hear experts from the St James Ethics Centre referring to resources such as Rushworth Kidder’s Moral Courage and How Good People Make Tough Choices which had become central to the development of our project. It was also good to see the model developed by St James for ethical decision making. In principle, it shares the steps of our model, but ours is far more simple to suit Year 9 students. As with our research into thinking routines, teachers on the project team broadened their pedagogical knowledge of teaching ethics through our experimentation with different models, formal professional development and extensive reading and discussions of different 3 approaches. - Problem Solving As we have worked on this project, we have drawn on research into problem solving. The spine of our model comes from the amalgamation of the five step risk assessment model already in use in Science classrooms and the problem solving model already in use in the PDHPE classrooms. In terms of enculturation, it was very useful to build on models with which the students were already familiar. When the project members from Science and PDHPE introduced these models, it proved to be a rich pedagogical discussion of how these models could be useful in other subject areas. Serendipitously, our Mathematics department has been working with Charles Lovitt, an education consultant whose area of expertise is problem solving in Mathematics. He presented a staff workshop that explored opportunities for cross-curricular problem solving and made explicit links between Mathematics and ethical concerns such as nuclear power and gambling. This proved an excellent stimulus for the teachers who had questioned the relevance of the Ethics Toolkit for subjects like Mathematics and reinforced the importance of a shared language and approach to encourage ethical behaviour. We have kept Harold Barrows (1996) six principles of for problem-based learning at the heart of the model: - Learning is student centred; - Learning occurs in small groups; - Teachers are facilitators or guides to learning; - Problems are the original focus or stimulus for learning; - Problems are the vehicle for the development of clinical problem solving skills; and - New information is directed through self-directed learning. - Cross-curricular Collaboration Our project has brought together a cross-curricular team that would not normally collaborate on academic matters. It has provided opportunities for better understanding of the skills taught in our Year 9 programs and has made apparent areas of overlap and opportunities for us to work together in the future. The outcomes of this type of collaboration means we are able to provide a greater sense of connections for our students. We are able to lift our thinking out of our subjects and give students a sense of the big picture which helps to foster engagement and motivation. (Perkins, 2010) - Academic care Our school currently has the “dichotomous approach” to the pastoral and academic domains. However, this project provided an opportunity to merge the two domains. The project team consisted of teachers who represented different Year 9 subjects, but were also Year 9 pastoral care teachers. It meant that the project saw a genuine link between what was happening in pastoral care and the academic classrooms. This was a significant step in the right direction towards Academic Care for our school. 4 - Krathwohl’s Taxonomy of the Affective Domain The project team has also used Krathwohl’s Taxonomy of the Affective Domain to guide our work. While we could see that our five step process fit neatly within Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain by working its way into the highest order of thinking, the affective domain is more difficult to measure. However, we are certain that our model helps guide students from the lowest level of “receiving” to the second highest level of “organisation”. It is not possible to measure the highest level of “characterisation by a value set” in the short time of this grant. This will only be seen in the students’ later lives, but we have provided them a tool to work their way up through the taxonomy and at least understand what steps they take to make a difficult decision. - Action Research Using the Action Research framework of the AGQTP has been a good source of professional development as well. For some on the project team, it was the first time they had undertaken a formal action research project. For others, it proved a good opportunity for mentoring less experienced staff members. It provided us the opportunity to research, plan and reflect in a way that strengthened the finished product. It also has provided us with a framework through which to approach subsequent program development and evaluation. Pedagogy strengthen the currency and depth of teachers’ learning area knowledge and understanding? - Pedagogies viewed through subject lens Teachers on the project team were afforded the opportunity to reflect on the pedagogies listed above through their subject lens. The team meetings provided rich discussion of how the pedagogies were applied across the different subjects which was enlightening for all. - Programming Through the programming and planning that happened to find opportunities to implement the routine, all team members were able to review the work done in their learning area and look for areas of improvement and refinement. Because the team included heads of department and classroom teachers it provided a formal opportunity for mentoring in the area of program development. It was a good opportunity to look at the Stage 5 syllabus outcomes for each of the subjects involved in the project. It was particularly useful for the Science and PDHPE departments to look at the overlap between their programs. The project catalysed for these two departments a much wider mapping exercise that will be undertaken at a later time. - Familiarity with Australian Curriculum When this project was initially conceived the Australian Curriculum documents were in consultation and each subject area was looking for meaningful ways to implement the general capabilities. The project time afforded Mathematics, Science, History and English to familiarise themselves with the new documents and consider how existing teaching programs could be adapted to suit the new requirements and enriched to include the new general capabilities. This has been a very valuable exercise despite the delay in the implementation of the new documents. 5 - Leading Implementation Another key component of this project was the sharing of the resource by the project team with their individual departments. This was an opportunity for the classroom teachers involved in the project to pioneer something in their faculties with the support of their heads of department. In each case, it was the classroom teacher, not the head of department, who drove the implementation of the project in their faculty. c) Sustainability How will the school overcome the effects of changes, such as personnel and funding, to see the project initiatives sustained? The sustainability of this project is guaranteed by the forthcoming implementation of the Australian Curriculum. The documents mandate “ethical behaviour” in the general capabilities. This will be the responsibility of every faculty. Each faculty will be required to show how it is addressing this requirement. The Ethics Toolkit is a simple way for teachers to quickly and effectively address the outcome. The fact that the toolkit can be used as a one-off lesson makes it very easy to implement. Similarly, because the kids are familiar with the language and the routine, it can be quickly implemented when the opportunity arises in a lesson. The generic nature of the routine means it works in any subject. Historically, affective outcomes are difficult to measure, but this simple thinking routine enables teachers to scaffold ethical behaviour for their students. While the true test of ethical behaviour will likely occur beyond the classroom walls, teachers can guarantee that the students are equipped with the steps to make a measured decision. The toolkit is embedded in programs for English, PDHPE, Science and Pastoral Care for 2012 for both Year 9 and Year 10. While our initial intent was to roll-out the approach more widely in 2012, we have decided to continue to refine its use in Year 9 where it is introduced and to build on the knowledge of the Year 10 students who began using the model in 2011. There is also a possibility it will be incorporated in an existing Year 11 pastoral care unit on ethics in 2012. The school has recently employed a graphic designer who is looking at the design of our posters. Throughout 2011, we have not been entirely happy with the design of our resources, so she will look at making our materials a bit more polished and dynamic. Similarly, further development of an online tool is in progress. This may take the form of a smart phone application enabling students to take the routine with them outside the school walls. The project has been very well received by the school and it has been well publicised by the teachers participating in the project. The project marries nicely with the school’s five core values – care, courage, responsibility, respect and integrity. A formal presentation will be made to all staff at a K-12 staff meeting early in 2012 which further raise the profile of the project and potentially encourage other faculties and staff members who were not involved in the initial project to use the toolkit. 6 d) Resources Please list and describe the resources/products developed eg learning resource, unit/s of work, audio files, worksheets, teaching designs. How can they be accessed? Please provide contact details for resources that are not made available for the AIS website. Ethics Toolkit Thinking Routine (A4 flyer) Ethics Toolkit Thinking Routine Teacher resource Ethics Toolkit Thinking Routine Prompt Cards for Students Project implementation plan Link to online resource Powerpoint for Project Launch Ethical Dilemmas used at the launch Teaching programs for English, Science, PDHPE Teacher lesson reflections for Science, English and PDHPE Pastoral Care program for Year 9 Student work samples Ethics pre-test/post-test Analysis of data from pre/post texts Bibliography 7