"Walter Singer`s Journey: the Story Behind a Community Plaza

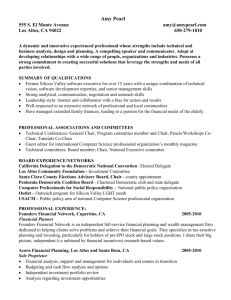

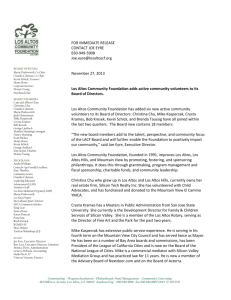

advertisement

Walter Singer’s Journey: the Story Behind a Community Plaza Memorial by Robin Chapman It has been just twenty-two years since Walter Singer died, not much time, as history goes. But it has been just long enough for many to have lost the thread of Walter Singer’s remarkable life story. During his lifetime, he was so active in local organizations and so much loved and admired, people affectionately called him Mr. Los Altos. Following his untimely death, civic leaders dedicated a sculpture to him in the newly remodeled Community Plaza. The bronze bust, created by artist Ingrid Jackson MacDonald, is now listed on the Smithsonian Art Inventory of sculpture in public places. When the Los Altos City Council voted recently to remove the bust and remodel the Plaza, council member Jarrett Fishpaw put it this way: “I walked in Community Plaza most of my life without a single trace or clue as to the impact the gentleman immortalized there had on the community." Who was this man whose bronze tribute has graced downtown Los Altos for two decades? Walter Singer was born in Germany in 1923, the son of a Lutheran mother and a Jewish father. In 1935, Nazi laws in Germany stripped Jews of citizenship rights and outlawed marriage between Jews and non-Jews. The Singers were now in danger. In 1939, after his father was arrested, the family fled to San Francisco with the help of a cousin. “I arrived pretty much with the clothes on my back,” Walter Singer said in an oral history, now in the Los Altos History Museum. “An extra set of underwear, an extra pair of shoes and four dollars in my pocket.” As his mother found work cleaning houses, a friend told them about Frank and Josephine Duveneck, a philanthropic couple who might help. When Mrs. Duveneck visited the Singers in San Francisco in the fall of 1939 and saw their tiny apartment, she went into action. Within an hour she had bundled Walter Singer into her blue Ford for the drive down the peninsula to Hidden Villa Ranch. At the Duvenecks’ warm, friendly table, the sixteen-year-old began to flourish. “I wanted some more potatoes,” he later recalled. “And asked for them in German, which the word for potatoes is kartoffel, and nothing happened; so until I finally thought of the right thing to say in English, I guess is when I had the additional helping of potatoes! They made me learn English, which was the best thing that ever happened to me in my life.” Eager to learn more, Singer enrolled in Palo Alto High School, heading down the hill to school each morning with the Duvenecks’ son Bernard. After graduation, and two years at Golden Gate University, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving as a translator during World War II. When the war was over he learned his father had died in a Nazi concentration camp. He became a U.S. citizen, found a job, and, at a dance in San Carlos, met Marie Ohanian, who became his wife. The two were wed at Hidden Villa Ranch. They moved to Los Altos Hills in 1961 and in 1976 purchased Los Altos Stationers, then located in the building now occupied by Le Boulanger. After their teenage daughter Julie was killed by a drunken driver, Singer turned more and more to a life of service. From the Rotary and the Los Altos Village Association, to the United Way and the Chamber of Commerce, he volunteered. As one of the founders of the Festival of Lights Parade in Los Altos, it was Walter Singer who climbed aboard a float each year to play Santa Claus for the children. Then, in 1989 Singer got shattering news. He had contracted AIDS from a tainted blood transfusion given to him during open heart surgery five years earlier. He was stunned. “I didn’t tell anyone besides my wife and son,” he said, “because of the stigma attached to AIDS.” Several months later, fearing the reaction of his customers, he quietly sold his store, telling friends he had decided to retire. In the meantime, he heard about a fellow Rotarian, former Los Altos High School principal Dushan “Dude” Angius, whose son Steve had contracted AIDS. He spoke to Angius and learned about the Los Altos Rotary AIDS Project. “I told him he would feel much better—and might help a lot of other people—if he would talk about it,” says Angius, now 86. “After six months of vacillating back and forth,” Singer said, “I decided to go public.” When he took the podium at the Los Altos Rotary meeting, December 7, 1989, only Dude Angius and their friend Mary Prochnow knew what he planned to say. “I’m going to talk to you today about a matter of life and death,” he began, as a hush fell over the crowd and he choked back tears. When he stopped speaking, “Every member, some crying, some unable to speak, came up and gave me a hug,” said Singer. “I had asked my fellow Rotarians if they would be my support group and they came through one hundred percent.” In return, he spent the remaining years of his life educating others about the egalitarian nature of disease. In the 1980s, people who were diagnosed with AIDS faced a death sentence and a public that frequently condemned them. Walter Singer worked to change that. He spoke to dozens and dozens of organizations. His story went national and then international—from the CBS Morning News to headlines in more than four hundred newspapers. He took on a featured role in the Rotary film, The Los Altos Story, a Peabody Awardwinning documentary that has been seen by millions of people worldwide. Jane Reed, Rotarian and past president of the board of the Los Altos History Museum put it this way: “It’s not taboo to talk about AIDS anymore. We have people like Walter Singer to thank for that.” He was just sixty-eight years old when he died in 1992. His funeral—presided over by both a rabbi and a protestant minister— drew hundreds of people. Two years later, the city he loved dedicated a tribute to him in a small Los Altos plaza and hundreds more people turned out for the ceremony. Today, the Walter Singer bust is something busy people might not notice as they hurry about. But the journey it represents is striking. It began in Germany just a few years short of a century ago, and led a refugee to a new life in America. “Walter was a giver,” says Dude Angius, summing up this man’s life. Repeatedly, instead of turning inward in sorrow, he found the strength to turn his sorrow into service. Bronze sculptures aside: this is Walter Singer’s lasting legacy.