Early Modern Historiography

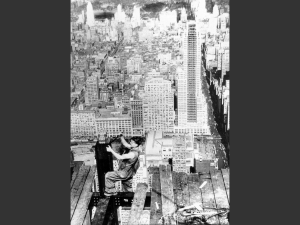

advertisement

European World: Introduction The term ‘early modern’ and its history Why did it become popular? Early modernity as a period of transition Modernisation and ‘modern’ Starting points and end points Was there a geographically-shared early modern world? Themes of social and economic change, religion, culture and politics may change at different speeds. Why study it? Change and continuity Sense of difference and different possibilities Parallels with modernity eg religion and communications As a testing ground for new approaches to history Practicalities Website: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/undergraduate/modules/hi203/ Beat Kumin (ed.) The European World 1500-1800 (2009) Attend both lectures (team taught) and seminars Key intended learning outcomes: o To develop skills o To develop a basic understanding of the major social, economic, political, and cultural changes that took place in early modern Europe o To recognise and evaluate points of comparison between different national political, social, economic and cultural systems The Historiography of Early Modernity The ‘early modern’ has also been in the forefront of testing/developing new approaches to history. The inheritance: Ranke and Political History: Tradition of ‘empiricism’ or ‘positivism’ (the description of observable phenomena). Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886): founding father of history as a professional discipline (archives; footnotes; source criticism; seminars); emphasis on high politics and diplomacy; History of the Latin and Teutonic Nations (1824): wie es eigentlich gewesesen (‘how it actually was’); reputation for factual narratives of orthodox political history; focus on states and great men (‘world historical figures’); allegedly ‘scientific’ (verification; objectivity); in reality much more complex: key role for empathy (imagination and intuition) and for art/drama/style (pen portraits, flashbacks). Often a narrative of progress and improvement (‘Whig history’). History as Social Science: The Annales School: Founding figures: Marc Bloch (1886-1944), Lucien Febvre (1878-1956); Journal Annales d’Histoire Economique et Sociale (founded 1929); renamed Annales: Economies, Societies, Civilisations (1946). Later exponent: Fernand Braudel (190285); The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (1948). Annalistes hostile to German empiricism; rejection of political history and of exclusively archival sources; aimed at l’histoire totale, drawing on the methodologies of the new social sciences (sociology, demography; geography). Emphasis on continuity (la longue duree), enduring structures of geo-history: landscape, climate: ‘the Mediterranean was 99 days long’. Events = ‘crests of foam that the tides of history carry on their strong backs’. Critics (esp Marxists) claimed lacked a proper theory of change. The New Social History: ‘History From Below’: Particularly British and US scholars frustrated with the ‘structuralism’ of the Annales school; desire to recover the agency of subordinate groups (the poor, the governed, women), esp. the popular mentalities of subordination. Heavily influenced by Marx, but rejected the ‘vulgar Marxism’ which saw only significant change as economic. But too concerned with past as inspiration for contemporary political struggles? Selective concentration on lower class ‘heroes’? Microhistory: Microhistory rejects, grand totalizing or quantitative approaches in favour of detailed studies of individuals or events. Ginzburg’s ‘cosmos of a 16th c. miller’ investigated by the Inquisition; Natalie Davis’, The Return of Martin Guerre (1983). Using ‘microscope’ will reveal underlying patterns, mentalities, structures. Problem of ‘typicality’ – undue focus on the bizarre and abnormal? Influence of cultural anthropology - Clifford Geertz’s ‘thick description’. The Linguistic Turn: Post Modernism and Post-Structuralism: Our sources (texts) not a description or reflection of a recoverable truth, but themselves through their inner relationships and tensions construct meaning (death of the author). For historians has lead to focus on representation and discourses, and idea that things we might take for granted (the body, sexual difference) are socially and culturally constructed. Logic of postmodernism destroys history? No recoverable ‘truths’ about the past; texts refer to nothing beyond themselves; no ‘narrative’ intrinsically more reliable or valuable than any other. Too disengaged from lived experience/human suffering? Early modern period a peculiarly effective testing ground for new approaches to the discipline of history. Many borrowings from other disciplines (sociology, anthropology, literary studies). Mark Knights Oct 2012