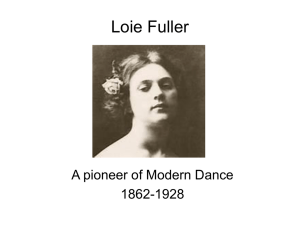

woman in the nineteenth century

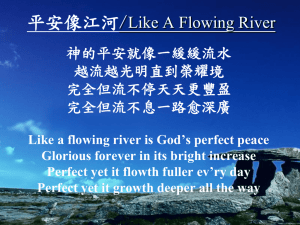

advertisement