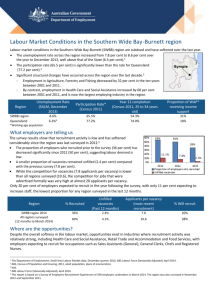

The capacity of families to support young Australians: financial

advertisement