Hattie`s Checklist for Visible Learning

advertisement

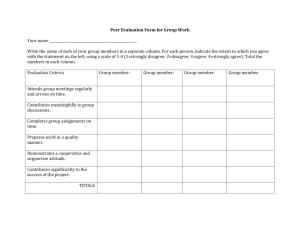

Key Leaders Network March 2013 Alabama Best Practices Center Learning Targets 1. To explore the practice of teaching as defined by John Hattie and to reflect on the implications for professional learning in my district and/or school(s) 2. To deepen my understanding of resistance as an impediment to change and to identify key concepts and strategies that I might use in working with resistance 3. To think about Instructional Rounds and determine our team’s interest in participating in a Spring Round 4. To provide input to ABPC staff regarding future sessions of KLN Learning Design 9:30 Welcome and Overview of Day Warm-Up: What’s the Greatest Challenge? Revisiting Hattie: What is the Relative Impact on Student Learning? — Individual Response to Questionnaire and Group Dialogue The Practice of Teaching According to Hattie Examination of Checklist for “Visible Learning Inside” Individual (or Team) Response to Mind Frames Section of Checklist Individual Reflection and Pair Sharing—Say Something Working with Resistance What is Resistance? Individual Reflection and Synectic Response to Quotes—Quick Write Fullan’s Resistance Mindset Learning from Peter Block o The ‘Faces’ of Resistance—Individual Ratings and Work in Groups o “Dealing with Resistance”—3 A’s Text Protocol o Naming the Resistance in Conversation with Clients ABPC’s Spring Instructional Rounds Team Time Team Processing and Planning—Here’s What, So What?, Now What? Team Response to ABPC Survey 2:30 ADJOURN 1 Activity 1: Rating Hattie’s Factors That Influence Student Learning Directions: John Hattie conducted an extensive review of the research on variables associated with student achievement. In the first column of the chart below are “influences” identified in the literature. Indicate the impact you believe each factor has on student achievement by placing a checkmark beneath the correspondent column—“High,” “Medium,” or “Low.” INFLUENCE HIGH IMPACT MEDIUM LOW Ability grouping/tracking/streaming Acceleration (for example, skipping a year) Comprehension programs Concept mapping Cooperative vs. individualistic learning Direct instruction Feedback Gender (male compared to female achievement) Home environment Individualizing instruction Influence of peers Matching teaching with student learning styles Meta-cognitive strategy programs Phonics instruction Professional development on student achievement Providing formative evaluation to teachers Providing worked examples Reciprocal teaching Reducing class size Retention (holding back a year) Student control over learning Student expectations Teacher credibility in eyes of the students Teacher expectations Teacher subject matter knowledge Teacher-student relationships Using simulations and gaming Vocabulary programs Whole language programs Within-class groupings 2 Activity 2: Examination of Checklist for ‘Visible Learning Inside’ Directions: 1. Form a small group with others who have your assignment. 2. Name a facilitator, recorder/reporter, and materials manager. 3. Review the items associated with the section of the Checklist assigned to your group. a. First, read the item to be certain that everyone in your group is clear on what is meant by the item. b. Look back in the chapter associated with your section to clarify meaning as necessary. 4. Talk together about the following questions: a. Which of the items would you have predicted to be important to effective teaching and learning? b. Which, if any, of the items do you have questions about—or might you not have associated with effective teaching and learning? c. Which one would you select as the most important of the items? 5. Now, consider how you might wish to use this section of the Checklist and information found in the related chapter back in your districts or schools. As you dialogue about possible uses, think about the following: a. To what extent do you believe the practices associated with your section are prevalent in classrooms across your districts/schools? b. To what degree do you believe administrators and teachers are aware of the importance of practices associated with your component? c. What might be the benefits of professional learning focused on this area? 3 Hattie’s Checklist for Visible Learning #1 Inspired and Passionate Teaching Strongly Disagree 1 Generally Disagree 2 Partly Disagree 3 Partly Agree 4 Generally Agree 5 1. All adults in this school recognize that: a. there is variation among teachers in their impact on student learning and achievement; Strongly Agree 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 b. all (school leaders, teachers, parents, students) place high value on having major positive effects on all students; and 1 2 3 4 5 6 c. all are vigilant about building expertise to create positive effects on achievement for students. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 b. supports learning through analysis of the teachers’ classroom interaction with students; 1 2 3 4 5 6 c. helps teachers to know how to provide effective feedback; 1 2 3 4 5 6 d. attends to students’ affective attributes; and 1 2 3 4 5 6 e. develops the teachers’ ability to influence students’ surface and deep learning. 1 2 3 4 5 6 2. This school has convincing evidence that all of its teachers are passionate and inspired—and this should be the major promotion attribute of this school. 3. This school has a professional development program that: a. enhances teachers’ deeper understanding of their subject(s); 6 4 4. This school’s professional development also aims to help teachers to seek pathways towards: a. solving instructional problems; 1 2 3 4 5 6 b. interpreting events in progress; 1 2 3 4 5 6 c. being sensitive to contest; 1 2 3 4 5 6 d. monitoring learning; 1 2 3 4 5 6 e. testing hypotheses; 1 2 3 4 5 6 f. demonstrating respect for all in the school; 1 2 3 4 5 6 g. showing passion for teaching and learning; and 1 2 3 4 5 6 h. helping students to understand complexity. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 5. Professionalism in this school is achieved by teachers and school leaders working collaboratively to achieve ‘visible learning inside.’ Excerpt from Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, by John Hattie (Routledge, 2012), pp. 23-34. 5 Hattie’s Checklist for Visible Learning— #2 Planning Strongly Disagree 1 Generally Disagree 2 Partly Disagree 3 Partly Agree 4 Generally Agree 5 6. The school has, and teachers use, defensible methods for: a. monitoring, recording, and making visible, on a ‘just in time’ basis, interpretation about prior, present, and targeted student achievement; Strongly Agree 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 b. monitoring the progress of students regularly throughout and across years, and this information is used in planning and evaluating lessons; 1 2 3 4 5 6 c 1 2 3 4 5 6 7. Teachers understand the attitudes and dispositions that students bring to the lesson, and aim to enhance these so that they are a positive part of learning. 1 2 3 4 5 6 8. Teachers within the school jointly plan series of lessons, with learning intentions [targets] and success criteria related to worthwhile curricular specifications. 1 2 3 4 5 6 9. There is evidence that these planned lessons: a. involve appropriate challenges that engage the students’ commitment to invest in learning; 1 2 3 4 5 6 b. capitalize on and build students’ confidence to attain the learning intentions; 1 2 3 4 5 6 c. are based on appropriately high expectations of outcomes for students; 1 2 3 4 5 6 d. lead to students having goals to master and wishing to reinvest in their learning; and 1 2 3 4 5 6 e. have learning intentions and success criteria that are explicitly known by the student. 1 2 3 4 5 6 creating targets relating to the effects that teachers are expected to have on all students’ learning. 6 10. All teachers are thoroughly familiar with the curriculum—in terms of content, levels of difficulty, expected progressions—and share common interpretations about these with each other. 11. Teachers talk with each other about the impact of their teaching, based on evidence of student progress, and about how to maximize their impact with all students. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 Excerpt from Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, by John Hattie (Routledge, 2012), pp. 37-68. 7 Hattie’s Checklist for Visible Learning #3 Starting the Lesson Strongly Disagree 1 Generally Disagree 2 Partly Disagree 3 Partly Agree 4 Generally Agree 5 12. The climate of the class, evaluated from the student’s perspective, is seen as fair; students feel that it is okay to say ‘I do not know’ or ‘I need help’; there is a high level of trust and students believe that they are listened to; and students know that the purpose of the class is to learn and make progress. Strongly Agree 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 13. The staffroom has a high level of relational trust (respect for each person’s role in learning, respect for expertise, personal regard for others, and high levels of integrity) when making policy and teaching decisions. 1 2 3 4 5 6 14. The staffrooms and classrooms are dominated more by dialogue than by monologue about learning. 1 2 3 4 5 6 15. The classrooms are dominated more by student that teacher questions. 1 2 3 4 5 6 16. There is a balance between teachers talking, listening, and doing; there is a similar balance between students talking, listening, and doing. 1 2 3 4 5 6 17. Teachers and students are aware of the balance of surface, deep, and conceptual understanding involved in the lesson intentions. 1 2 3 4 5 6 18. Teachers and students use the power of peers positively to progress learning. 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 19. In each class and across the school, labeling of students is rare. 1 2 3 4 5 6 20. Teachers have high expectations for all students, and constantly seek evidence to check and enhance these expectations. The aim of the school is to help all students to exceed their potential. 1 2 3 4 5 6 21. Students have high expectations relative to their current learning for themselves. 1 2 3 4 5 6 22. Teachers choose the teaching methods as a final step in the lesson planning process and evaluate this choice in terms of their impact on students. 1 2 3 4 5 6 23. Teachers see their fundamental role as evaluators and activators of learning. 1 2 3 4 5 6 Excerpt from Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, by John Hattie (Routledge, 2012), pp. 69-91. 9 Hattie’s Checklist for Visible Learning #4 During the Lesson: Learning Strongly Disagree 1 Generally Disagree 2 Partly Disagree 3 Partly Agree 4 Generally Agree 5 Strongly Agree 6 24. Teachers have rich understandings about how learning involves moving forward through various levels of capabilities, capacities, catalysts, and competences. 1 2 3 4 5 6 25. Teachers understand how learning is based on students needing multiple learning strategies to achieve surface and deep understanding. 1 2 3 4 5 6 26. Teachers provide differentiation to ensure that learning is meaningfully and efficiently directed to all students gaining the intentions of the lesson(s). 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 29. Teachers and students have multiple strategies for learning. 1 2 3 4 5 6 30. Teachers use principles from ‘backward design’ - moving from the outcomes (success criteria) back to the learning intentions, then to the activities and resources needed to attain the success criteria. 1 2 3 4 5 6 31. All students are taught how to practice deliberately and how to concentrate. 1 2 3 4 5 6 32. Processes are in place for teachers to see learning through the eyes of students. 1 2 3 4 5 6 27. Teachers are adaptive learning experts who know where students are on the continuum from novice to capable to proficient, when students are and are not learning, and where to go next, and who can create a classroom climate to attain these learning goals. 28. Teachers are able to teach multiple ways of knowing and multiple ways of interacting, and provide multiple opportunities for practice. Excerpt from Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, by John Hattie (Routledge, 2012), pp. 92- 114 10 Hattie’s Checklist for Visible Learning #5 During the Lesson: Feedback Strongly Disagree 1 Generally Disagree 2 Partly Disagree 3 Partly Agree 4 Generally Agree 5 Strongly Agree 6 33. Teachers are aware of, and aim to provide feedback relative to, the three important feedback questions: ‘Where am I going?’, ‘How am I going there?’; and ‘Where to next?’ 1 2 3 4 5 6 34. Teachers are aware of, and aim to provide feedback relative to, the three important levels of feedback: tasks, process, and self-regulation. 1 2 3 4 5 6 35. Teachers are aware of the importance of praise, but do not mistake praise with feedback information. 1 2 3 4 5 6 36. Teachers provide feedback appropriate to the point at which students are in their learning, and seek evidence that this feedback is appropriately received. 1 2 3 4 5 6 37. Teachers use multiple assessment methods to provide rapid formative interpretations to students and to make adjustments to their teaching to maximize learning. 1 2 3 4 5 6 38. Teachers: a. are more concerned with how students receive and interpret feedback; 1 2 3 4 5 6 b. know that students prefer to have more progress than corrective feedback; 1 2 3 4 5 6 c. know that when students have more challenging targets, this leads to greater receptivity to feedback; 1 2 3 4 5 6 d. deliberately teach students how to ask for, understand, and use the feedback provided; and 1 2 3 4 5 6 e. recognize the value of peer feedback, and deliberately teach peers to give other students appropriate feedback. 1 2 3 4 5 6 Excerpt from Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, by John Hattie (Routledge, 2012), pp. 115-137. 11 Hattie’s Checklist for Visible Learning #6 The End of the Lesson Strongly Disagree 1 Generally Disagree 2 Partly Disagree 3 Partly Agree 4 Generally Agree 5 Strongly Agree 6 39. Teachers provide evidence that all students feel as though they have been invited into their class to learn effectively. This invitation involves feelings of respect, trust, optimism, and intention to learn. 1 2 3 4 5 6 40. Teachers collect evidence of the student experience in their classes about their success as change agents, about their levels of inspiration, and about sharing their passion with students. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 41. Together, teachers critique the learning intentions and success criteria, and have evidence that: a. students can articulate the learning intentions and success criteria in a way that shows that they understand them; b. students attain the success criteria; c. students see the success criteria as appropriately challenging; and d. teachers use this information when planning their next set of lessons/learning. 42. Teachers create opportunities for both formative and summative interpretations of student learning, and use these interpretations to inform future decisions about their teaching. Excerpt from Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, by John Hattie (Routledge, 2012), pp. 138-146. 12 Hattie’s Checklist for Visible Learning Mind Frames Strongly Disagree 1 Generally Disagree 2 Partly Disagree 3 Partly Agree 4 Generally Agree 5 43. In this school, the teachers and school leaders: a. believe that their fundamental task is to evaluate the effect of their teaching on students’ learning and achievement; Strongly Agree 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 b. believe that success and failure in student learning is about what they, as teachers or leaders, did or did not do …We are change agents! 1 2 3 4 5 6 c. want to talk more about the learning than the teaching; 1 2 3 4 5 6 d. see assessment as feedback about their impact; 1 2 3 4 5 6 e. engage in dialogue, not monologue; 1 2 3 4 5 6 f. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 enjoy the challenge and never retreat to ‘doing their best’; g. believe that it is their role to develop positive relationships in classrooms/staffrooms; and h. inform all about the language of learning. Excerpt from Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning, by John Hattie (Routledge, 2012), pp. 149-166 13 Activity 3: Reflection on Hattie—Say Something I. Directions: Think back over Hattie’s key findings and implications for teaching practice that you have considered over the past hour or so. With these ideas as your focus, respond to the prompts in the table below. I didn’t know that . . .. II. I wonder about . . .. Directions: Stand up and find a partner not from your district. Share your reflections one with another. Then talk together about any ideas or resources in Visible Learning for Teachers that you are considering using with your faculty and staff. Notes: 14 Activity 4: Quotes Related to Resistance—Quick Write Directions: Select the quote with which you most resonate. Take 3-4 minutes to reflect on what this means to you and why you selected it. # Quote Quick Write “Reform often misfires because we fail to 1 2 3 learn from those who disagree with us. ‘Resistance’ to a new initiative can actually be highly instructive. Conflict and differences can make a constructive contribution in dealing with complex problems. As Maurer (1996) observes: Often those who resist have something important to tell us. People resist for what they view as good reasons. They may see alternatives we never dreamed of. They may understand problems about the minutiae of implementation that we never see from our lofty perch atop Mount Olympus.” (p. 49). – Michael Fullan “The key to understanding the nature of resistance is to realize that it is a reaction to an emotional process taking place within [an individual]. It is not a reflection of the conversation we are having . . . on an objective, logical, rational level. Resistance is a predictable, natural reaction against the process of being helped and the process of having to face up to difficult . . . problems.” Peter Block, p. 129 “ ‘The challenge,’ says Ferlazzo, ‘is to move people a large distance and for the long term, we have to create the conditions where they can move themselves.’ Ferlazzo makes a distinction between ‘irritation’ and ‘agitation.’ Irritation, he says is ‘challenging people to something that we want them to do.’ By contrast, ‘agitation is challenging them to do something that they want to do.’ What he has discovered throughout his career is that ‘irritation doesn’t work.’ It might be effective in the short term. But to move people fully and deeply requires something more—not looking at the student or the patient as a pawn on a chessboard but as a full participant in the game … ‘It means trying to elicit from people what their goals are for themselves and having the flexibility to frame what we do in that context.’”—Daniel Pink, p. 40 1. 2. 3. Michael Fullan, “Leadership for the 21st Century: Breaking the Bonds of Dependency,” Educational Leadership (April, 1998). Peter Block, Flawless Consulting, p. 121, (San Francisco: Pfeiffer, 2011) Daniel H. Pink, To Sell is Human, p. 40, (New York: Riverhead Books, 2012) 15 Activity 5: Naming the Resistance Directions: 1. Individually read through the following “faces of resistance” identified by Peter Block. Reflect on the extent to which you encounter each of these in your work from 1 = Not at All, to 4 = Frequently. 2. Select one of the “faces of resistance” that you encounter frequently. Write the number (1-9) on a 3x5 index card. Holding your card high, look for a match with 1-3 colleagues from other tables. Share your experiences in this area providing examples of situations in which you have experienced this. Talk together about what this resistance means to you and the potential damage it can cause when you are seeking to “get everyone on board” in pursuit of organizational goals. Create a visual to display your ideas. “FACES” OF RESISTANCE: 1. Give me more detail. When individuals keep asking for more specific and detailed information and are never satisfied with the amount of information you provide, you have probably encountered those who are cloaking their resistance in this unending quest for information. 2. Flooding you with detail. Sometimes individuals convey their resistance by overloading you with information about what they are trying or what they are doing regarding the issue at hand. 3. Time. Individuals may give lip service to your idea or proposal, but claim that the “timing is wrong,” or that they are just too busy at the moment to take this on. These individuals may be using time to mask their real opposition to what is being asked of them. 4. Impracticality. Individuals expressing this face of resistance talk about the “real-world” (or real classroom), suggesting that the proposed change is impractical, academic, and perhaps idealistic. Block suggests that it is the intensity with which individuals convey these messages that lets you know you are up against an emotional response. 5. Compliance. This exists when a staff member expresses a desire to get to implementation without any discussion of the issue—and without any energy or enthusiasm. Although difficult to identify, look out for those who act totally dependent on you and want to please. 6. Press for Solutions. These resistors ask continually for solutions, solutions, solutions. They do not want to think about issues or problems, but want to move directly to answers. 7. Attack. The most obvious form of resistance, this exhibits itself in confrontations filled with angry words and nonverbals. 8. Silence. Block writes “this is the toughest of all.” It is at play when your continual approaches to individuals yield no response at all. However, “silence never means consent.” 9. Confusion. These resistant individuals persist in claiming not to understand even after you have offered multiple explanations. FREQUENCY 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 16 Activity 6: Dealing with Resistance Three A’s Text Protocol: Assumptions, Agreements, Arguments Directions: Read through the excerpt from Flawless Consulting by Peter Block on the following page. As you read, look for three ideas that you can share with your group after the silent reading: an assumption the author is making, an idea with which you agree, and a concept with which you could argue. Record these ideas (and the location in the framework) below or on your copy of the framework. Be prepared to share each of them with your group members. Assumption (of author) _____________________________________________________________ Agreement (an idea with which I agree): _________________________________________________________ Argument (an idea that I could argue with): ______________________________________________________ Directions for the Three A’s Protocol After the group members have read and identified the three ideas above, identify someone to go first. 1. Begin with assumptions. The volunteer will read an assumption that he found and say why he selected this idea. In round robin fashion, other members of the group will share their assumptions. During the sharing, only one person speaks at a time; the “microphone” moves around the table as others listen carefully. 2. When all have shared, the group will briefly discuss the ideas that they heard. 3. Move to share “agreements.” One person will volunteer to go first, sharing an idea with which she agreed and why. In round robin fashion, other members 17 of the group will share their agreements, followed by an open discussion of these ideas. 4. Last, share “arguments.” Share around the table—with only one person speaking at a time—until all have shared. Then discuss at your table. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... “Dealing with Resistance,” Excerpt from Flawless Consulting, Third Edition, Peter Block, (San Francisco, Pfeiffer, 2011) “People use the phrase ‘overcoming resistance’ as though resistance or defensiveness were an adversary to be wrestled to the ground and subdued. ‘Overcoming resistance’ would have you get clever and logical to win the point and convince the [resistor]. But there is no way you can talk [someone] out of their resistance because resistance is an emotional process. Behind the resistance are certain feelings, and you cannot talk people out of how they are feeling. “There are specific steps [you] can take to help [individuals] get past the resistance and get on with solving problems. The basic strategy is to help the resistance blow itself out, like a storm, and not fight it head-on. Feelings pass and change when they are expressed directly. The skill is . . . to ask to put directly into words what they are experiencing—to ask [individuals] to be authentic. . . . “(p. 149) Three Steps for Handling Resistance “There are three steps for handling resistance: 1. Identify in your own mind what form the resistance is taking. The skill is to pick up the cues from the [resistor] and then describe to yourself what you see happening. 2. State, in a neutral, unpunishing way, the form the resistance is taking. This is called ‘naming the resistance.’ The skill is to find the neutral language. 3. Be quiet. Let the [resistor] respond to your statement about resistance.” (p. 151) Don’t Take It Personally “A [resistor’s] behavior is not a reflection on you. Most of us have a habit of analyzing what we did wrong . . .. The passion for self-criticism is very common and gets in the way of keeping the resistance focused on the [resisting individuals], where it belongs.” (p. 155) 18 “Remember that [individuals’] defenses are not to be denied. In fact, they need clear expression. If suppressed, they just pop up later and more dangerously. The key is how you respond to the defenses. “A couple of points to summarize: Don’t take it personally. Despite the words used, the resistance is not designed to discredit you. Defenses and resistance are a sign that you have touched something important and valuable. That fact is now simply coming out in a difficult form. Most questions are statements in disguise. Try to get behind the question to get the statement articulated. This takes the burden off you to answer a phantom question.” (p. 156) 19 What are Instructional Rounds? The Instructional Rounds process was developed by the Harvard Graduate School of Education, under the leadership of Richard Elmore. It is an explicit practice designed to bring discussions of instruction directly into the process of school improvement. There are two purposes to Instructional Rounds: 1. To build the skills of network members by coming to a common understanding of effective practice and how to support it. 2. Support instructional improvement at the host site by sharing what the network learns and by building skills at the local level. Participants gather in small teams of 3-5 people and visit 3 classrooms in the host school. They observe in each classroom for 15 minutes, looking for evidence of the host school’s “problem of practice,” which is an observable instructional practice that is a key focus of the school. The school identifies an area for which they seek data to continue improvement of that practice. Observations are based on the Instructional Core: Students Teachers Content The instructional core focuses on the “relationship between the teacher, the student, and the content—not the qualities of any one of them by themselves –that determines the nature of instructional practice, and each corner of the instructional core has its own particular role and resources to bring to the instructional process.” (p. 24) Participants involved in Instructional Rounds, set aside their traditional mode of observation and instead use “descriptive observation,” about which the authors write: The “kind of observing we’re talking about here focuses not on teachers themselves, but on the teaching, learning, and content of the instructional core. What is the task that students are working on? …by description we mean the evidence of what you see--not what you think about what you see.” (Instructional Rounds in Education, p. 84). As a result, “administrators often have to unlearn their well-honed skills of deciding rather quickly what a teacher needs to work on and instead take off their evaluating glasses and look with fresh eyes to see what is happening in and across classrooms.” (p. 84). During an Instructional Round, participants should ask three questions: 1. What are the students doing? 2. What is the teacher doing? 3. What is the instructional task? 20 Difference Between Judgmental and Nonjudgmental Language: Judgmental Language Nonjudgmental/Descriptive Language • Fast Paced • Teacher asks: “How did you figure out this problem? Student explains. • Too much time on discussion, not enough time on individual work • Student 1 asks student 2: What are we supposed to write down? • Teacher used effective questioning techniques with a range of students Student 2: I don’t know. • Teacher read from a book that was not at the appropriate level for the class We also ask participants to record “fine-grained” evidence. Fine-grained evidence is very specific and detailed. Fine-grained evidence does not categorize or make generalizations. Examples of Large-Grained Evidence • Lesson on the 4 causes of the Civil War • Teacher questions students about the passage they just read. • Teacher checked frequently for comprehension. • Teacher made curriculum relevant to students’ lives. Examples of Fine-Grained Evidence • Teacher: “How are volcanos and earthquakes similar and different? • Prompt for student essays: “What role did symbolism play in foreshadowing the main character’s dilemma?” • Whole group instruction. Over 8 minutes, teacher asked 12 questions. 5 of 24 students answered questions. Samples of a Problem of Practice: 1. In our school, students should have opportunities to be engaged in thinking, writing, investigating, reading and/or talking based on the essential question. Our December data from walk-throughs indicate that only 49% of our classrooms are engaging in these activities. As you visit our classrooms, we would like data related to the following questions: • • What is the nature of the task students are being asked to do in class? How does the level of the work reflect the verb required by the essential question or learning outcome? 2. At our school, our goal is to increase active and authentic student engagement by implementing 21st Century and Project Based Learning with embedded formative assessment. Using these methods students are able to apply their learning to real life situations and are able to communicate what is being learned to their peers or an observer. This is evidence that authentic learning has taken place. As you visit classrooms, use the following questions to guide your observation: What evidence do you see of authentic and active student engagement? To what extent is formative assessment embedded in the lesson? How is formative assessment used to modify instruction if necessary? In what ways are students able to communicate their learning to their peers or an observer? 21 District: ______________________________________ Team Reflection and Planning: Here’s What, So What? Now What? Directions: As a team, talk together about what you have learned or had reinforced as a result of this year’s participation in KLN (Here’s What). Then address what you consider to be the relevance or importance of these learning’s to you and your district/school. In other words, how does each relate to your ongoing work (So What?). Finally, talk about what you are doing/planning to do to put these learning’s into practice (Now What?) Please turn in one copy of this form as your exit pass. This will serve as input to our evaluation of KLN 2012-2013. HERE’S WHAT SO WHAT? NOW WHAT? 22 District: __________________________________ Key Leaders Network Survey: Planning for 2013-2014 1. To what extent do you value each of the following components of KLN? Please use a scale of 1 – 4, with 1 = not valuable and 4 = very valuable. a. Networking with colleagues from other districts 1 2 3 4 b. Planning with district team 1 2 3 4 c. Extending my knowledge about content 1 2 3 4 d. Learning protocols and strategies to use with adult learners 1 2 3 4 2. Consider the following possibilities for focus in next year’s KLN sessions. Rate your interest in each on a scale of 1 - 4, where 1 = not applicable and 4 = to a great extent a. Leadership 1 2 3 4 b. College- and Career-Ready Standards 1 2 3 4 c. Integrating technology into teaching and learning 1 2 3 4 d. Shifting to student-centered learning 1 2 3 4 e. Strategic thinking 1 2 3 4 f. Creating a common vision of effective teaching (PLC/communities of practice) 1 2 3 4 g. Other: ______________________________________________________ 23 3. What do you consider to be the strengths of the KLN? 4. What suggestions do you have for improving the KLN? 24