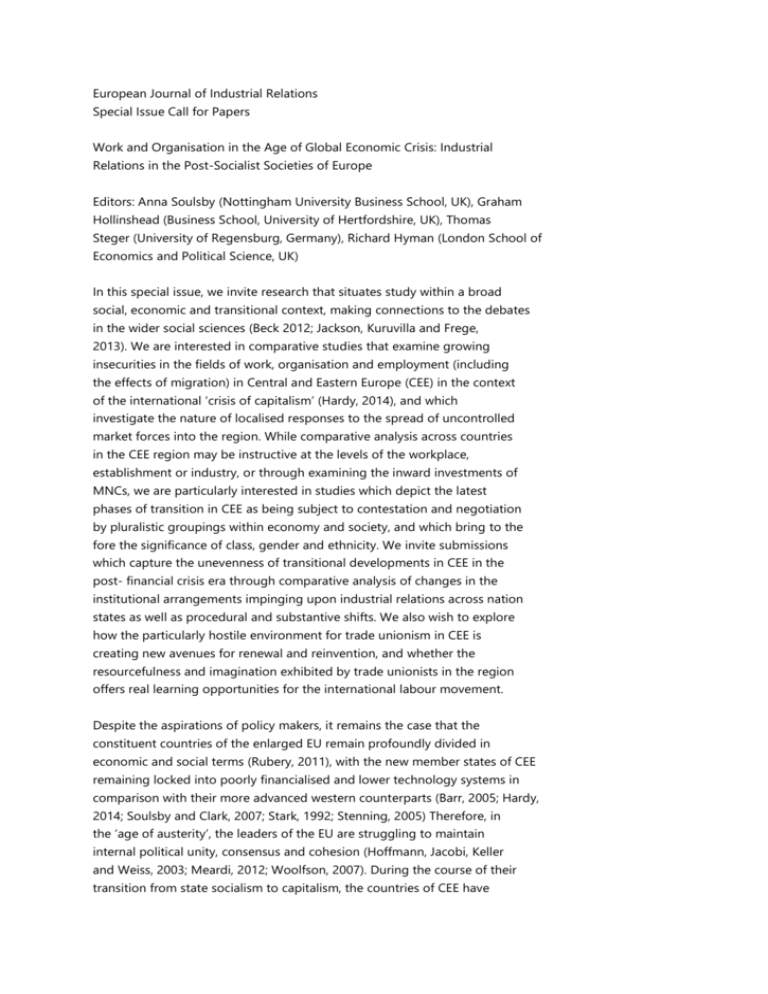

European Journal of Industrial Relations Call for Papers

advertisement

European Journal of Industrial Relations Special Issue Call for Papers Work and Organisation in the Age of Global Economic Crisis: Industrial Relations in the Post-Socialist Societies of Europe Editors: Anna Soulsby (Nottingham University Business School, UK), Graham Hollinshead (Business School, University of Hertfordshire, UK), Thomas Steger (University of Regensburg, Germany), Richard Hyman (London School of Economics and Political Science, UK) In this special issue, we invite research that situates study within a broad social, economic and transitional context, making connections to the debates in the wider social sciences (Beck 2012; Jackson, Kuruvilla and Frege, 2013). We are interested in comparative studies that examine growing insecurities in the fields of work, organisation and employment (including the effects of migration) in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) in the context of the international ‘crisis of capitalism’ (Hardy, 2014), and which investigate the nature of localised responses to the spread of uncontrolled market forces into the region. While comparative analysis across countries in the CEE region may be instructive at the levels of the workplace, establishment or industry, or through examining the inward investments of MNCs, we are particularly interested in studies which depict the latest phases of transition in CEE as being subject to contestation and negotiation by pluralistic groupings within economy and society, and which bring to the fore the significance of class, gender and ethnicity. We invite submissions which capture the unevenness of transitional developments in CEE in the post- financial crisis era through comparative analysis of changes in the institutional arrangements impinging upon industrial relations across nation states as well as procedural and substantive shifts. We also wish to explore how the particularly hostile environment for trade unionism in CEE is creating new avenues for renewal and reinvention, and whether the resourcefulness and imagination exhibited by trade unionists in the region offers real learning opportunities for the international labour movement. Despite the aspirations of policy makers, it remains the case that the constituent countries of the enlarged EU remain profoundly divided in economic and social terms (Rubery, 2011), with the new member states of CEE remaining locked into poorly financialised and lower technology systems in comparison with their more advanced western counterparts (Barr, 2005; Hardy, 2014; Soulsby and Clark, 2007; Stark, 1992; Stenning, 2005) Therefore, in the ‘age of austerity’, the leaders of the EU are struggling to maintain internal political unity, consensus and cohesion (Hoffmann, Jacobi, Keller and Weiss, 2003; Meardi, 2012; Woolfson, 2007). During the course of their transition from state socialism to capitalism, the countries of CEE have constituted prime subjects for the receipt of neo-liberal economic prescriptions for ‘reform’, notably as asserted by the ‘Troika’ comprising the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Far from such economic orthodoxy becoming discredited or reconsidered in the wake of the global financial turmoil of the late 2000s, it has become evident that such liberal market economic medicine has been dispensed to the CEE respondents with even greater alacrity in the post-financial crisis era. Yet the socio-economic context of countries in the region may be characterised by its vulnerability, as deepened integration into international economic structures has been accompanied by high levels of dependence on foreign investment and perilous exposure to the ebbs and flows of international capital. The crisis in neo-liberalism has therefore created disproportionate social and economic detriment amongst the working populations of CEE, and is manifested by malaises such as profound income disparity between rich and poor, high levels of precariousness in employment, emigration, homelessness, and the dismantling of already fragile systems for social welfare provision as well as institutional arrangements for collective bargaining and social partnership. While the CEE nations undoubtedly share common institutional features as a product of their transitional status, as well as experiencing a joint downward trajectory in exposure to global economic forces, novel theoretical departures are recognising ‘unevenness’ in the developmental paths of individual states. Hardy (2014), for example, finds the notion of sporadic ‘social leaps’ instructive in shedding light on the realities of transition in CEE, in preference to the much vaunted concept of the ‘transformation process’. Similarly, Myant and Drahokoupil (2010) posit a ‘typology’ of post-communist economies which combines indigenous political, economic and institutional factors with levels of national integration into the global economy in highlighting socio-economic distinctiveness between nations. Such theoretical departures are welcome as they serve to query the efficacy of ‘designer’ blueprints for neo-liberal reform as incepted by powerful western agencies at the outset of transition (Hardy, 2014; Myant and Drahokoupil, 2012). Instead, the ‘uneven’ perspective on transition in CEE opens the way for envisaging the reality of social and economic development in terms of negotiation and contestation by social agents, bringing to the fore issues such as class, gender and ethnicity (Hardy 2014). Indeed a cursory empirical perusal of the institutional state of play across the variety of CEE nations in the post-crisis era would reveal that a diverse array of ‘architectures’ are in evidence, with variability, in particular, being evident in the nature of collective bargaining structures, procedures for the delivery of social welfare, as well as in the rapidly changing substance and procedure of the employment relationship. Wider societal turbulence poses particular challenges for the citizens of CEE as they respond to the effects of the economic crisis and during the course of their daily experience of work (O’Reilly, Lain, Sheehan, Smale and Stuart, 2011). The working environment is increasingly characterised by volatility, precariousness, risk and uncertainty. For many workers, especially in the regions and local communities of the post-socialist countries of Europe, work and employment are now regarded with a sense of real insecurity and fear for the future (e.g. Bernhardt and Krause, 2014; Croucher and Morrison, 2012). Trade unions in CEE, whose organisation and structure has been in a state of flux over the period of transition, have experienced dwindling membership, a diminution of consultation rights as employers and governments have asserted policy ‘imperatives’ fuelled and legitimised by the crisis, as well as the decentralisation of bargaining structures and dilution of labour codes (Bernaciak, Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman, 2014). In a climate of apprehension, the response of organised labour to draconian actions of employers and governments has been understandably muted, yet there have been some notable examples of resistance as manifested in overt expressions of social unrest across the region. We would note in particular, the protests of thousands of public sector workers in Romania in May 2010 against planned cuts to wages and pensions, as well as the mobilisation of thousands by the three Lithuanian Confederations outside the Parliament building in January 2009. Perhaps paradoxically, as Bernaciak et al. (2014) suggest, despite the ravaging effects of austerity measures on trade union organisation, the union movement in CEE has found ways to respond to serious adversity in an imaginative and resourceful fashion. On one hand, this has apparently taken the form of a re-politicisation of union identity as leaders have moved to the fore in mobilising the working population against the elite-driven affronts on social and employment entitlements. On the other, more practical measures have been taken to rekindle trade union activism, notably through the utilisation of social media for communication purposes and through offering voice to marginalised and precarious groupings as well as those operating in the shadow economy. (Bernaciak et al., 2014). Key Dates and Contact Details Submission of extended abstracts (maximum 1000 words not including references): 29th December 2014 (24.00 CET). Submission of full papers: 31st July 2015. Please contact one of the guest editors for further information. Abstract submission should be sent by an e-mail attachment to one of the guest editors. Anna Soulsby, Nottingham University Business School, UK. anna.soulsby@nottingham.ac.uk Graham Hollinshead, Business School, University of Hertfordshire, UK. G.hollinshead@herts.ac.uk Thomas Steger, University of Regensburg, Germany. T.steger@wiwi.uni-regensberg.de Richard Hyman, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK (Editor: European Journal of Industrial Relations). r.hyman@lse.ac.uk References Barr, N. (Ed.) (2005). Labor Markets and Social Policy in Central and Eastern Europe: The Accession and Beyond. Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank. Beck, U. (2012). Redefining the Sociological Project: The Cosmopolitan Challenge. Sociology. 46(1): 7-12. Bernaciak, M., Gumbrell-McCormick, R. and Hyman, R. (2014). Trade Unions in Europe: Innovative Responses to Hard Times. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Dept. for Central and Eastern Europe. April: 1-29. Bernhardt, J. and Krause, A. (2014). Flexibility, Performance and Perceptions of Job Security: A Comparison of East and West German Employees in Standard Employment Relationships. Work, Employment and Society. 28(2): 285-304. Croucher, R. and Morrison, C. (2012). Management, Worker Responses, and an Enterprise Trade Union in Transition. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society. 51(1): 583-604. Hardy, J. (2014). Transformation and Crisis in Central and Eastern Europe: A Combined and Uneven Development Perspective. Capital & Class. 38(1):143–155. Hoffmann, R., Jacobi, O., Keller, B. and Weiss, M. (2003). (Editors). European Integration as a Social Experiment in a Globalized World. Düsseldorf: Hans-Böckler-Stiftung. Jackson, J., Kuruvilla, S. and Frege, C. (2013). Across Boundaries: The Global Challenges Facing Workers and Employment Research. British Journal of Industrial Relations. 51(3): 425–439. Meardi, G. (2012).Union Immobility? Trade Unions and the Freedoms of Movement in the Enlarged EU. British Journal of Industrial Relations 50(1): 99–120. Myant, M. and Drahokoupil, J. (2010). Transition Economies: Political Economy in Russia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Wiley. Myant, M and Drahokoupil, J. (2012). International Integration, Varieties of Capitalism and Resilience to Crisis in Transition Economies. Europe-Asia Studies, 64 (1): 1-33. O’Reilly, J., Lain, D., Sheehan, M., Smale, B. and Stuart M. (2011). Managing Uncertainty: The Crisis, its Consequences and the Global Workforce. Work, Employment and Society. 25 (4): 581-595. Rubery, J. (2011). Reconstruction Amid Deconstruction: Or Why We Need More of the Social in European Social Models. Work, Employment and Society. 25(4): 658-674. Soulsby, A. and Clark, E. (2007). Organisation Theory and the Post-Socialist Transformation: Contributions to Organisational Knowledge. Special Issue. Human Relations. 60(10): 1419–1442. Stark, D. (1992). Path Dependence and Privatization Strategies in East Central Europe. East European Politics and Societies. 6(1): 17-53. Stenning, A. (2005). Where is the Post-Socialist Working Class? Working-Class Lives in the Spaces of (Post-)Socialism. Sociology. 39(5): 983-999. Woolfson, C. (2007). Labour Standards and Migration in the New Europe: Post-Communist Legacies and Perspectives. European Journal of Industrial Relations. 13(2): 199-217.