Endometriosis

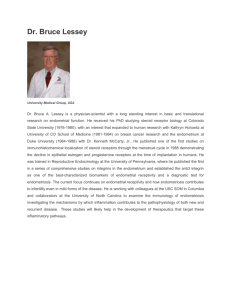

advertisement