Reference Observation

advertisement

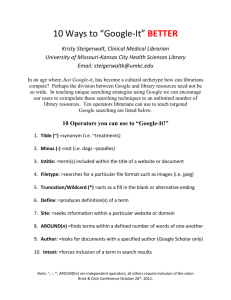

Alexandra Orchard LIS 6120: Access to Information Reference Observation Essay Professor: Jen Pecoskie, MLIS, Ph. D. The Impact of Google on the Work of Reference Librarians As with any new reference tool, the proliferation of the Google search engine brought changes to the reference librarian’s overall role and day-to-day work. However, the changes associated with the advent of Google are more impactful than those associated with most new reference tools because Google is a resource not left primarily in the hands of reference librarians; it is accessible to most library users, both in and out of the confines of the library. Thus, Google has not only been integrated into the reference librarian’s toolbox, but into the user’s, thereby changing not only how reference librarians approach some aspects of reference work, but the type of reference work that users require. Google’s impact on Internet users has been profound, directly affecting library users by making information more readily available, thereby changing the search process. This indirectly affects reference librarians by changing the emphasis of their role in the user’s search process from search starter and primary information finder to information evaluator, additional information gatherer, and educator. Additionally, Google has also had a direct effect on reference librarians’ work by becoming an integrated tool in the reference librarian’s toolkit. Changing Needs and Search Habits of Users As Google became ubiquitous, the amount and categorization of questions asked by patrons at the reference desk evolved. The demand for ready reference decreased (Arndt, 2010), although questions of this type still occur, often from non-computer users. For example, during an observation a user approached the reference desk asserting that she “can’t work a computer” and asked the following ready reference question, “Where do bedbugs live and what do you do if you have them” (Observation, 2011)? The example above demonstrates that reference librarians still receive ready reference questions, just on an infrequent basis. This was confirmed by the observation data where only nine of 31 reference questions fell into the ready reference category (Appendix A). The data also showed that reference librarians used Google to answer six of the nine ready reference questions. Not only has Google diminished the need for ready reference, it also modified the point in the search process when users approach reference librarians. When asked about the overall impact of Google on her work, one librarian lamented, Sundays used to be busier; this really changed since the Internet and World Wide Web because it changed the nature […] kids can do the research on their own, and don’t come in until they need a print source. Librarians [are] brought in later in [the] search process. (Observation, 2011) Indeed, research indicates that users in general are turning first to the Internet and Google to initiate information gathering, rather than making the reference librarian the entry point of the search process. This may take place at home or at a terminal within the library and is likely due to the perceived easiness, accessibility, and usefulness of Google. As Egger-Sider and Devine (2006) explain, Google’s interface is simple, unintimidating, and it provides what users perceive as instantaneous, relevant results. This follows the assertion made by Bell (2005) that most users are content to “satisfice” themselves by finding information through means that are easy, quick and produce what the user considers a “good enough” (p. 68) result. Google provides an easily accessible and intuitive resource for users, allowing them to do just that. Users1 are not information experts with the proper training to evaluate the information provided by Google; also, the search engine’s simplicity and easiness often masks the reality that the results provided are often not the most appropriate for the research (Egger-Sider & Devine, 2006). This provides reference librarians ample opportunities to assist users with information evaluation, gather additional information based on what the user has already found, and act as educator for information literacy and reference resources. Indirect Impact on Reference Librarians Reference Librarian as Information Evaluator Although the role of information evaluator has always been one of the key services performed by reference librarians (Cassel & Hiremath, 2009), with the proliferation of Google it has taken on greater significance. This is due to reference librarians now assisting users with the evaluation of sources found throughout the course of the user’s research. Arndt (2010) asserts that “while Google and its ilk took away the demand for ready reference it created a new need for service to users overwhelmed by the fire hose of information, both credible and incredible, unleashed on the Internet” (p. 7). As discussed above, the demand for ready reference still exists, but is in decline, in part because of Google’s impact on user’s search behaviors; conversely there is an increase in demand for the evaluative expertise provided by the reference librarian. This expertise is of particular value to the user who begins the information quest with Google. A typical Google search returns a numerous list of results, that although are in relevance order, are not necessarily all relevant or of the best quality (EggerSider & Devine, 2006). By seeking help from a reference librarian, the user can receive clarification on what information is of good quality and meets the user’s needs versus information that is of low quality. This evaluation presents the reference librarian with an opportunity to educate the user in information literacy, a role discussed in more detail later. As stated by 1 Egger-=Sider and Devine specify “students,” however; this may be generalized to include all users. 2 librarian Heidemann (2011) at the Canton Public Library, “Now [the librarian’s] role is helping people to parse what they find, it’s helping people but in a different light […] you have coping skills as an information professional and most of the public doesn’t.” Herring (2006) echoes this sentiment by making the comparison that “the web, even with Google, is like some gigantic haystack and the user is faced with finding that one needle” (p. 39). This assertion can be taken further, as a user may find hundreds of needles within the proverbial Google haystack, but needs a reference librarian to determine which of these needles is “that one needle” (p. 39). Thus the role of reference librarian as information evaluator has increased. Reference Librarian as Additional Information Gatherer Heidemann also noted, “even digital natives don’t always get their needed information [using Google]” (2011). This is because despite the numerous results returned by Google, the content and quality of the results are often not sufficient to meet the user’s needs. This is particularly the case for school and scholarly research. Cohen (2006) asserts that “the problem is that the search engines that we use to answer “ready reference” questions (the easy stuff) are the same engines being used by students who are writing a term paper (the harder stuff)” (p. 29). Indeed, when users are unable to find “that one needle” (Herring, 2006, p. 39), the reference librarian is usually brought into the search process to find additional information. Reference librarians have an array of reference resources with which to provide the user additional information. According to Rethlefsen (2008), although helpful, Google is not always the right resource for the search and can hinder the users, producing an “overwhelming, frustrating and time-consuming” (p. 13) experience. This presents the reference librarian with the opportunity to assist the user with a more appropriate reference resource, whether it be a print book, journal, database or even the library’s catalog to build upon the user’s search and identify additional sources. Perhaps one of the most important resources is the “Invisible Web.” While almost all users are aware of the “Visible Web” (content found using search engines such as Google), most are unaware of the “Invisible Web” which contains all of the content found on the World Wide Web that is not indexed by Google or other search engines, such as proprietary databases (Egger-Sider & Devine, 2006). In addition to informing users of the Invisible Web’s existence, Egger-Sider and Devine note that reference librarians are also instrumental in helping users to navigate and use the search tools provided on the Invisible Web like hierarchical directories which users often do not have experience using. Reference librarians play a crucial role in the user’s search. Although usually not part of the user’s initial search process, the reference librarian can still make an impact by helping the user find additional sources by navigating through the resources at the reference librarian’s disposal. By doing so, the reference librarian aids in educating the user on Google’s limitations and tool usage. 3 Reference Librarian as Educator The reference librarian is uniquely poised to function as educator. By evaluating the information collected by the user, the reference librarian is enabled to teach the user information literacy skills. Likewise, the process of helping users find additional sources enables the reference librarian to assist users in improving search skills and techniques suited to tools beyond Google. A downside to using the Internet in general, but specifically using Google to do research, is that “evaluation falls to the user” (Cassel & Hiremath, 2009, p. 276). As noted above, one of the key roles of the reference librarian has always been to evaluate sources, but another role is to help the user to understand the library, and this includes helping the user to understand and assess information obtained during the search process (Cassel & Hiremath, 2009). When approached later in the search process, after the user has already gathered some information, the librarian has a unique opportunity to sit with the user and review the retrieved information. The user’s needs may require the reference librarian to utilize additional reference tools to obtain more research materials. In this case, the reference librarian can utilize the user’s initial experience searching Google as an educational tool to help users become comfortable with various library resources. Cahill (2008) suggests that by utilizing Google as a tool to explain “new concepts and […] library resources” helps to “build their understanding both of the search process and the resources available to them” (p.78). Additionally, Cahill (2008) provides the example of parlaying a non-full text article found via Google Scholar into teaching the user about the library’s databases while fulfilling the user’s need to find the full text version of the article (p. 72). Cirasella (2007) concurs with this educational approach and suggests that Google is a good tool to begin with as it “engages” the user, and when “patrons are engaged, they are better able to absorb instruction so librarians are better able to teach best search practices […] on Google apply to other reference resources as well” (p. 2). Direct Impact on Reference Librarians Google has also had a direct impact upon reference librarians, becoming a tool integrated into the reference librarian’s toolbox, particularly for ready reference questions and as the starting point of a more in-depth reference question. However, Google is most effective as a ready reference source. This was consistent with the observation data that showed that Google was used in two-thirds of the ready reference questions, but not used in any of the non-ready reference interactions (Appendix A). Indeed, reference librarians do not limit themselves to using Google, instead recognizing that no single resource or tool will work for all queries and users (Rethlefsen, 2008). Instead, reference librarians utilize the reference resource that is most appropriate and helpful to the given reference question, balancing the accessibility and efficiency with the information needs of the patron. In one case, the reference librarian was approached by a non-computer user who needed the phone number to the Do Not Call Registry. Rather than instantly go to Google, the librarian searched a phone 4 number index put together by the local librarians. Although the number was not listed and the librarian had to use Google anyway, the librarian’s initial instinct was not “Google it!” but instead “how can I find the information most efficiently” (Observation, 2011). Kohl (2007) asserts that reference librarians should ask themselves “can a commercial Web search engine provide better and more appropriate scholarly information than a library catalog” (p. 316)? Although not all of the questions asked by patrons were scholarly in nature, based on the observation, the answer to Kohl’s question is a resounding “no.” The online library catalog was the most used reference resource tool, used in 14 out of 31 user reference interactions, where as Google was only used six times. Therefore, it is clear that while reference librarians recognize the value of Google, its appropriateness is also understood. While useful in ready reference, when a more appropriate resource or tool is called for, the reference librarian heeds the call. Conclusion Google has impacted the search behaviors of users as well as the role played by reference librarians. Whereas users previously turned to reference librarians to answer ready reference questions and initiate searches, many users now do not consult the reference librarian until after beginning the research process with Google. This has transferred the emphasis of the reference librarian’s role from search initiator to information evaluator, additional information provider and educator. Additionally, Google directly impacted the methods that reference librarians use to perform searches. Although reference librarians still tend to use the appropriate source based on the user’s question, Google is now a mainstay in the referenced librarian’s toolbox when it comes to answering ready reference questions. 5 Appendix A Breakdown of Resource Tools used to Answer Reference Questions/Source Acquisitions into Ready Reference and non-Ready Reference Categories Observation 02/04/11 1.5 hours 02/10/11 1.5 hours 02/19 1.5 hours 03/04/11 1 hour 03/06/11 1.5 hours 03/10/11 1 hour Totals Aggregate Totals Ready Reference Google Other resource 2 0 Non-Ready Reference Google Catalog Other Resource 0 0 1 .5 .5 0 1 1 .5 .5 0 7 4 1 0 0 1 0 .5 .5 0 4 2 1.5 1.5 0 1 0 6 3 0 14 22 8 9 Explanatory Notes: .5 is used when a question was answered using two resources (e.g., Google and the library catalog). Two was the maximum number of resource seen used for a single reference interaction. Non-ready reference questions incorporate all user-reference librarian interactions that are not ready reference or service/help questions. See Appendix B for further categorization information. 6 Appendix B Breakdown of Interactions between Reference Librarians and Users through Observation Observation 02/04/11 1.5 hours 02/10/11 1.5 hours 02/19 1.5 hours 03/04/11 1 hour 03/06/11 1.5 hours 03/10/11 1 hour Totals Aggregate Totals Total Patron Interactions Face-to-face Phone Total RQs/Source Acquisitions 4 1 2 0 Other Resource 1 7 0 0.5 1 1.5 4 28 4 0.5 7 4.5 20 7 1 1 1 0 6 17 1 0.5 4 2.5 11 8 2 1.5 1 1.5 6 71 9 6 14 31 11 49 49 80 Google Catalog Total Service/Help Questions 2 Explanatory Notes: .5 is used when a question was answered using two resources (e.g., Google and the library catalog). Two was the maximum number of resource seen used for a single reference interaction. RQs/Source Acquisitions include questions such as ready reference, finding a specific source (book, magazine, etc.), and providing an answer to a non-service question (i.e. involved research, looking for a source, etc.). Service/Help Questions include customer service questions and tasks such as copy/print (including paying for print outs), directions to the restroom, and signing up for computer use. 7 References Arndt, T. S. (2010). Services in a (post) Google world [Editorial]. Reference Services Review. 38(1). 7-9. Bell, S. J. (2005). Submit or Resist: Librarianship in the Age of Google. American Libraries. 36(9). 68-71. Cahill, K. (2008). Google Tools on the Public Reference Desk. The Reference Librarian, 48(1), 67-79. Cassel, K. A, & Hiremath, U. (2009). Reference and Information Services in the 21st Century. New York: Neal-Schuman. Cirasella, J. (2007). You and Me and Google Makes Three: Welcoming Google into the Reference Interview. Library Philosophy and Practice. (June). LPP Special Issue on Libraries and Google. p.NA. Cohen, S. M. (2006). Thinking and Researching-Don’t Just ‘Google It.’ Information Today. 23(6). 28. Egger-Sider, F. & Devine, J. (2006). Google, the Invisible Web, and Librarians. Internet Reference Services Quarterly. 10(3). 89-101 Heidemann, Anne. Department Head, Children’s, Tween, & Teen Services. (2011, March 16). Interview by A. Orchard. Discussion about Policies, Procedures, and the Librarian’s Role at Canton Public Library. Herring, M. Y. (2006). A Gaggle of Googles. Internet Reference Services Quarterly. 10(3). 37-44. Kohl, D. F. (2007). Alas, Poor Catalog, I knew Thee Well… [Editorial]. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 33(3). 315-316. 8 Observation at Suburban Public Library. (2011). Rethlefsen, M.L. (2008). Easy ≠ Right. Library Journal Netconnect. Summer 2008. 1214. 9