Like many nativist organizations opposed to immigration, the

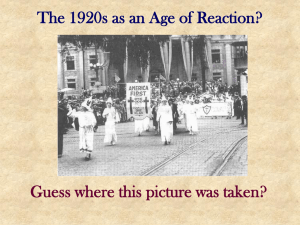

Like many nativist organizations opposed to immigration, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan responded to cultural changes brought about not only by immigration, but also by changes in the American economy and society after the First World War. Rapid technological, economic, demographic, social, and cultural changes understandably created confusion and cultural tension in the early 1920s. Mass production, mass consumption, mass communications, and mass culture undermined the familiar cultural codes and traditional morals and values. The Ku Klux Klan attempted to resist challenges to traditional morality by enlisting native, white, Protestant Americans who exhibited character, morality,

Christian values, and "pure Americanism."

Most Americans today imagine the average Klansman as a bigoted, intolerant, ignorant, southern redneck who burned crosses, terrorized black Americans, and intimidated opponents while hiding behind white sheets and a conical hood. While many of these images are based in fact, the Klan of the 1920s had little in common with the Klan of the 1860s or of the

1960s. The second of five distinct Klan eras, the Klansmen of the 1920s resembled fraternal, temperance, and progressive reform organizations, albeit with a coercive (and sometimes downright terrorist) edge. In their effort to preserve an idealized "golden age" of American life, most Klan activities focused on defending white, Christian civilization, promoting community activities, enforcing morality, and combating corruption and concentrated economic power. Most of the

Klan's political activity was local, non-partisan, and aimed at enforcing morality and sobriety. One of the Klan's most important moral campaigns was for the restoration of law and order as exemplified by adherence to the 18th Amendment.

Like all the iterations of the KKK, the second Klan was marked by a hatred of African Americans. The Klan, especially in the South, was wedded to the ideals of white supremacy and the maintenance of racial purity. Klan members in northern states also became alarmed when thousands of African Americans migrated to northern industrial cities in search of work and competed with white workers there. Furthermore, the experience of black veterans during World War I had a galvanizing effect on African Americans and made them less likely to accept passively white supremacy after defending the nation against enemies abroad.

One factor that made the Klan of the 1920s unique, however, was its intensified hostility toward immigrants,

Catholics, and Jews. The Klan's anti-Catholicism stemmed from the belief that Catholics could not be good

Americans if they maintained allegiance to the pope. Furthermore, they believed Catholics sought exclusion from mainstream America by maintaining their own schools. In the Klan's view, priests threatened intact families by exerting greater influence over women and children than the male head of household. Klan propaganda hysterically portrayed Catholics as potentially winnowing their way into government (à la Al

Smith) and turning America over to Rome. Klan members were also suspicious of Jewish Americans, charging that they paid allegiance to Palestine and purportedly controlled international banks. Many Americans held (and

still hold) such views, and they were abetted in their thinking by anti-Semitic newspapers such as Henry Ford's

Dearborn Independent .

In addition, the second Klan was a mass movement with chapters across the entire country, not just in the South.

According to some historians, the KKK of the 1920s established one of the largest social movements of the 20th century, enrolling nearly five million of ordinary, "respectable," middle-class Americans, both urban and rural, from coast to coast and from South to North. In fact, Midwestern states harbored the largest number of

Klansmen, particularly the state of Indiana.

Klan members were also dismayed and even appalled by the "new woman" of the 1920s. In 1920, women found new freedom in the public sphere: they showed their independence by voting, working, dressing with "sex appeal," or smoking and drinking in public spaces such as speakeasies. Mass media—radio, magazines, advertising, and especially movies—portrayed women as sexual beings, and films included nudity that shocked

Victorian sensibilities. Committed to protecting the "purity of White Womanhood," the Klan physically punished those who engaged in immoral behavior, public indecency and drunkenness, wife beating, gambling, adultery, and the failure to support one's family. Interestingly, the Klan supported women's suffrage since women could help restore and preserve morality and traditional values by voting for Klan agendas and political candidates.

Demise

The demise of the Second Klan after 1925 resulted from internal corruption and external circumstances. Internal scandals, embezzlement, and immoral behavior at high levels created distrust and disrespect for some Klan officials. One of the most egregious examples is that of D. C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of Indiana and a major figure in the Klan hierarchy, who embezzled funds, raped his secretary and allowed her to die after a suicide attempt, for which he received a sentence of life in prison. Also, the inherent secrecy of the Klan, a lack of accountability, and the large incomes from dues tempted and corrupted officials at all levels. Furthermore, Klan leaders failed to live up to Klan principles. Klan founder, "Colonel" Simmons, was forced from his office in the early 1920s as a result of heavy drinking and poor management. The owners of the Southern Publicity

Association, Clarke and Tyler, scandalized members after they were discovered together drunk and half-naked in an Atlanta hotel room.

Moreover, the political and economic circumstances that attracted people to the Klan changed after 1924 for many reasons. Congress enacted restrictions on immigration in 1921 and in 1924. The economy soared to high levels of productivity and prosperity; consumer goods were plentiful. Union activity declined during the 1920s and the labor movement remained weak (membership in the American Federation of Labor fell by 1.5 million).

Al Smith, the Catholic governor of New York, lost his bid for the presidency in 1924. The threat of

"Bolshevism" had diminished and Hollywood movie makers responded to public criticism by toning down nudity and morally offensive material. Furthermore, the Klan secrecy and fanaticism generated opposition: the

Klan failed to win broad political support while political opposition against it solidified. Some states passed legislation, such as the Walker Law in New York in 1923, to regulate the Klan or similar organizations. By the end of the 1920's, the Klan dissolved as a social movement only to return later under different social and political circumstances.