Set A

New Horizons space probe gets first closeups of Pluto; scientists thrilled

By Scientific American, adapted by Newsela staff

08.07.15

NASA Senior Public Affairs Officer Dwayne Brown (left) moderates a New Horizons science

update with participants. Photo: NASA/Flickr

The unmanned spacecraft New Horizons has just completed its most difficult job. It had to pass

over Pluto as close as it could without being damaged. Its job was to take pictures to send back to

Earth. The spacecraft was controlled by scientists in Maryland. They work with NASA, the U.S.

space agency.

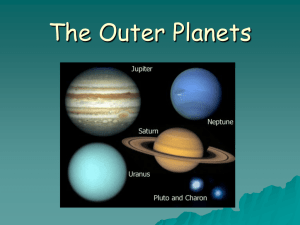

Pluto is the most distant object ever visited in space. Scientists used to say it was the ninth planet

from the sun. But now they call it a dwarf planet because it is smaller than the other planets.

Mysterious Pluto

The spacecraft almost did not go to Pluto at all. Sending a spacecraft into space is very

expensive. At first NASA could not find enough money to make it happen. However, many

people asked NASA to launch the Pluto trip. Eventually, NASA found the money.

Scientists have always been interested in Pluto. For a long time, they did not know very much

about it. Then in the 1990s scientists learned some new information. The Hubble Space

Telescope showed light and dark areas on the planet. Still, that is all they knew. New Horizons

tells a much more detailed story about Pluto.

Scientists have been studying the last picture the spacecraft sent back to Earth. It is more detailed

than anything they have seen before. It shows one side of Pluto that faces away from its main

moon, Charon. On the surface of Pluto there appears to be a heart-shaped area. The scientists

believe it may be icy. The two sides of the heart are different colors. It could mean Pluto is made

up of different kinds of chemicals.

More Pictures On The Way

New Horizons is not finished sending back pictures. It will send more detailed pictures in the

coming weeks. It will even send pictures of some of Pluto's moons.

Scientists have made other discoveries too. Pictures from New Horizons show that the planet is

bigger than they thought.

The spacecraft also proved there are five moons around Pluto. These moons are called Charon,

Hydra, Nix, Styx and Kerberos.

Pictures Surprise Scientists

Pictures sent back to Earth show the differences between the surface of Pluto and its largest

moon, Charon. “Now we see how dramatically different they really are," said scientist Alan

Stern. He says the pictures show "a much younger surface on Pluto and an older, more battered

surface on Charon." Pluto appears to have craters that have been filled in. Now they are smooth

areas.

It is now clear that Pluto is quite different from Neptune’s moon Triton. For a long time

scientists thought they might look alike. “It’s unbelievable how alien this place is,” Stern said of

Pluto. For example, it is much redder than Triton. Pluto's surface looks more like the planet

Mars.

Flying Away From The Sun

This is only the beginning of New Horizon’s trip to space. It will also study the other, darker side

of Pluto. Then it will search for planetary rings lit from behind by the sun. In September the

spacecraft will send all its information on Pluto back to radio telescopes on Earth.

New Horizons has enough power to keep taking pictures of space for about another 20 years. By

then it will be about twice as far from the sun as it is now.

Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2015 Scientific American, a division of Nature

America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Set A

Aug. 4, 2015 NASA

What Is Pluto?

This picture, taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, shows five moons orbiting the distant, icy dwarf planet Pluto.

Credits: NASA, ESA, Mark Showalter (SETI Institute)

A drawing of the solar system shows Pluto's tilted orbit. Pluto's orbital path angles 17 degrees above the line, or plane,

where the eight planets orbit.

Credits: NASA

An artist's drawing shows the New Horizons spacecraft as it nears Pluto. The moon Charon is in the distance.

Credits: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute (JHUAPL/SwRI)

This article is part of the NASA Knows! (Grades K-4) series.

What Is Pluto?

Pluto was discovered in 1930 by an astronomer from the United States. An astronomer

is a person who studies stars and other objects in space.

Pluto was known as the smallest planet in the solar system and the ninth planet from

the sun.

Today, Pluto is called a “dwarf planet.” A dwarf planet orbits the sun just like other

planets, but it is smaller. A dwarf planet is so small it cannot clear other objects out of its

path.

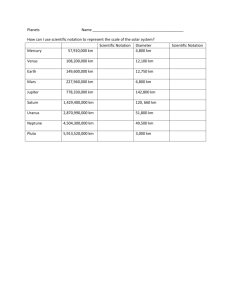

On average, Pluto is more than 3.6 billion miles (5.8 billion kilometers) away from the

sun. That is about 40 times as far from the sun as Earth. Pluto orbits the sun in an oval

like a racetrack. Because of its oval orbit, Pluto is sometimes closer to the sun than at

other times. At its closest point to the sun Pluto is still billions of miles away.

Pluto is in a region called the Kuiper (KY-per) Belt. Thousands of small, icy objects like

Pluto are in the Kuiper Belt.

Pluto is only 1,400 miles (2,300 kilometers) wide. That's about half the width of the

United States. Pluto is slightly smaller than Earth's moon. It takes Pluto 248 years to go

around the sun. One day on Pluto is about 6 1/2 days on Earth.

Pluto was named by an 11-year-old girl from England. The dwarf planet has five moons.

Its largest moon is named Charon (KER-ən). Charon is about half the size of Pluto.

Pluto's four other moons are named Kerberos, Styx, Nix and Hydra.

Why Is Pluto Not Called a Planet Anymore?

In 2003, an astronomer saw a new object beyond Pluto. The astronomer thought he had

found a new planet. The object he saw was larger than Pluto. He named the object Eris

(EER-is).

Finding Eris caused other astronomers to talk about what makes a planet a "planet."

There is a group of astronomers that names objects in space. This group decided that

Pluto was not really a planet because of its size and location in space. So Pluto and

objects like it are now called dwarf planets.

Pluto is also called a plutoid. A plutoid is a dwarf planet that is farther out in space than

the planet Neptune. The three known plutoids are Pluto, Eris and Makemake (MAH-keeMAH-kee). Astronomers use telescopes to discover new objects like plutoids.

Scientists are learning more about the universe and Earth's place in it. What they learn

may cause them to think about how objects like planets are grouped. Scientists group

objects that are like each other to better understand them. Learning more about faraway

objects in the solar system is helping astronomers learn more about what it means to be

a planet.

What Is Pluto Like?

Pluto is very, very cold. The temperature on Pluto is 375 to 400 degrees below zero.

Pluto is so far away from Earth that scientists know very little about what it is like. Pluto

is probably covered with ice.

Pluto has about one-fifteenth the gravity of Earth. A person who weighs 100 pounds on

Earth would weigh only 7 pounds on Pluto.

Most planets orbit the sun in a near-circle. The sun is in the center of the circle. But

Pluto does not orbit in a circle! The orbit of Pluto is shaped like an oval. And the sun is

not in the center. Pluto's orbit is also tilted.

How Is NASA Exploring Pluto Today?

NASA learns about Pluto from pictures taken with telescopes. Pictures from the Hubble

Space Telescope helped scientists find the four smaller moons.. Hubble has also taken

pictures of Pluto's surface. The pictures show dark and light areas on Pluto. Pluto is so

far away that even pictures taken by telescopes in space are a little fuzzy.

In 2006, NASA launched the first mission to Pluto. It is called New Horizons. New

Horizons is a spacecraft that is going to the edge of the solar system. The spacecraft is

about the size of a piano. It was a nine-year trip to reach Pluto. In 2015, New Horizons

arrived at Pluto. The mission will spend more than five months studying Pluto and its

moons. New Horizons will then study other objects in the Kuiper Belt.

New Horizons has cameras that will take pictures of Pluto. The spacecraft also has

science tools to gather information about Pluto. These pictures and information will help

scientists learn more about the dwarf planet.

Why Is NASA Exploring Pluto?

NASA sends spacecraft to other planets because exploring space is exciting. It helps

people learn new things. Spacecraft have visited every major planet in the solar system.

Studying places like Pluto may help scientists learn how planets form.

Set B

New criteria for what makes a planet means

Pluto still doesn’t make the cut

Sorry Pluto, you’re out. Again.

PETER DOCKRILL

27 NOV 2015

When Pluto was ousted from the ranks of planethood about a decade ago,

people were aghast. Here was a former ‘planet’ many of us had learned about

in school, now relegated to mere ‘dwarf planet’ status by virtue of its modest

size and some other quibbling technicalities. The indignity of it all!

Since then – and particularly recently in light of much excitement over

theongoing discoveries made by NASA’s New Horizons mission – there have

beenrepeated calls for Pluto to be promoted back to the ranks of planets

proper, but according to a proposal for new criteria to define what a planet is,

Pluto sadly still doesn’t make the cut.

Jean-Luc Margot, an astronomer with the University of California, Los Angeles

(UCLA), says the current 2006 definition for what makes a planet, which was

determined by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in somewhat

controversial circumstances, applies only to bodies in our Solar System,

creating“definitional limbo” for newly discovered bodies.

The current definition is a planet is a celestial body that orbits the Sun

(meaning our Sun, not any other star), is nearly round, and can clear the

neighbourhood around its orbit – which means that it is the dominant body in

its region of space.

As framed by the IAU in 2006, this definition only applies to planets in our own

Solar System, and that’s a problem. Extrasolar planets, also known as

exoplanets, are covered separately under a complementary 2003 draft

guideline for the definition of planets, although it hasn’t been universally

accepted.

The chief problem with the definition of ‘planet’ then, as Margot explains, is

that it discounts the thousands of exoplanets we know about that exist in other

solar systems. And that’s not all.

“Beyond that, the roundness criterion is problematic,” he told Deborah

Netburn at the Los Angeles Times. “The size at which an object becomes

round spans a whole range of values depending on its temperature, interior

strength and thermal evolution. None of these things are observable from

Earth for exoplanets right now.”

Instead, Margot’s proposal, viewable online at arXiv.org and set to be

published in The Astronomical Journal, states that a planet should be defined

as a celestial body that is in orbit around one or more stars or stellar

remnants, which has sufficient mass to clear the neighbourhood around its

orbit, and has a mass below 13 Jupiter masses.

According to the astronomer, this simpler and less arbitrary definition provides

numerous benefits, and will make it easier for us to consistently identify and

practically recognise new exoplanets as we discover them. Plus, it’s a

definition for a planet that applies to everything out there that qualifies,

regardless of where that happens to be.

“There is an equation behind it, and that removes some of the ambiguities in

the existing definition,” he said. “Also, when you write down the equation for

clearing an orbit to a specific extent in a specific time frame, it turns out that it

depends only on the mass of the star, the mass of planet and the orbital

period of the planet. One of the main advantages of the proposed criterion is

all those things can easily be measured by Earth – and space-based

telescopes.”

It’s unknown whether the new proposal will be accepted by the IAU, although

it’s probable the body will consider it at its next general assembly in 2018.

One of the factors that may make the revised definition more palatable to the

scientists calling the shots is that it draws upon concepts previously

considered by the IAU – and importantly, doesn’t rock the boat in terms of

what’s considered a planet inside our own Solar System.

“Pluto’s status isn’t changed. Pluto is not a planet. It very clearly fails to clear

its orbital zone, by this definition or the previous definition,” Margot said. “I

love Pluto. It is an amazing and fascinating world that is worthy of study, and

none of that is diminished because of its classification.”

Set B

(NOBODY KNOWS)

Is Pluto a planet? The answer may surprise you.

by Danielle Wiener-Bronner from Fusion News

In two weeks, NASA’s New Horizons mission will fly by Pluto, after spending

nearly a decade in space. Pluto, as you may recall, was stripped of its planetary

title back in 2005, for reasons that some scientists think are bogus. Now, they’re

hoping to welcome Pluto back to the planetary club.

In 2005, scientists discovered a large, rocky object close to Pluto. The discovery

of Eris put scientists in an intergalactic pickle—should they make Eris the tenth

planet in our solar system, or sacrifice Pluto and make them both dwarf planets?

Because Eris is larger than Pluto, it would be inconsistent for scientists to leave

well enough alone.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) finally reached a

decision. They issued an official definition of a planet:

“A Celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for

its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic

equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighbourhood around

its orbit.”

… and an official definition of a dwarf planet:

“A celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for

its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic

equilibrium (nearly round) shape, (c) has not cleared the neighbourhood around

its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.”

Plut is not a satellite, meaning it doesn’t orbit another planet. It orbits around the

sun, like other planets, and it is round.

Part (c) is where Pluto fails to make the cut. IAU’s definition put the issue to

rest: Eris is in the “neighbourhood around Pluto’s orbit,” and vice versa.

Pluto is a dwarf planet, Eris is a dwarf planet, we have eight planets in our solar

system, case closed.

TwitterTweetFaceboo kSharePinterestPin ItCopy image

web.gps.caltech.edu/~mbrown/planetlila/

Except, the decision turned out to be pretty emotional, and not all that scientific.

For some, the decision was a triumph. “Pluto is dead,” Astronomer Mike

Brown—one of the scientists responsible for ousting Pluto from our solar

system—said upon hearing the IAU’s decision. Brown eventually wrote a book

called How I Killed Pluto: And Why It Had It Coming. His Twitter handle

is @plutokiller. He’s really into having helped put the kibosh on Pluto as a

planet.

On the other side of the spectrum we find Alan Stern, New Horizon’s principal

investigator. According to Stern, Pluto’s always been a planet to him. He told

NewsWorks: “I don’t know a single expert, a single planetary scientist, that

thinks that the astronomers made a good definition…So we pretty much ignore

it.”

Basically, Stern adds, a planet is a large, round object in space: “We recognize

big, round objects, rounded by gravity, as planets. It’s about that simple.” Plus,

he says, once we see close-up images of Pluto it will be really hard for us not to

think of it as a planet.

Former NASA scientist Phil Metzger laid the situation out rather bluntly in an

interview with Deutsche Welle. When asked, “Do you think we will call Pluto a

“planet” again in the near future?” he answered:

“We are free to call it a planet right now. The planetary science community has

never stopped calling bodies like Pluto “planets.”

Metzger said that Pluto planet advocates should start “calling Pluto a planet

right now,” adding: “Add to the consensus, because that’s how science makes

progress, by one person at a time being convinced of the truth and adopting it.”

You heard him, Pluto Truthers. Make your move.

Set C

Why is Pluto no longer a planet?

By Paul Rincon

Science editor, BBC News website

13 July 2015 Science & Environment

Nasa's New Horizons mission made a close pass of Pluto this week. For more than 70

years, Pluto was one of nine planets recognised in our Solar System.

But in 2006, it was relegated to the status of dwarf planet by the International Astronomical

Union

(IAU). So why was Pluto demoted?

Where did the controversy start?

Pluto was discovered in 1930 by US astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, who was using the Lowell

Observatory in Arizona.

Textbooks were swiftly updated to list this ninth member in the club. But over subsequent

decades, astronomers began to wonder whether Pluto might simply be the first of a population of

News Sport Weather Shop Earth Travel

12/11/2015 Why is Pluto no longer a planet? BBC

News

http://www.bbc.com/news/scienceenvironment33462184

2/13

small, icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune.

This region would become known as the Kuiper Belt, but it took until 1992 for the first

"resident"

to be discovered. The candidate Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) 1992 QBI was detected by David

Jewitt and colleagues using the University of Hawaii's 2.24m telescope at Mauna Kea.

How did this change things?

Confirmation of the first KBO invigorated the existing debate. And in 2000, the Hayden

Planetarium in New York became a focus for controversy when it unveiled an exhibit featuring

only eight planets. The planetarium's director Neil deGrasse Tyson would later become a vocal

figure in public discussions of Pluto's status.

But it was discoveries of Kuiper Belt Objects with masses roughly comparable to Pluto, such as

Quaoar (announced in 2002), Sedna (2003) and Eris (2005), that pushed the issue to a tipping

point.

Eris, in particular, appeared to be larger than Pluto giving

rise to its informal designation as the

Solar System's "tenth planet".

Prof Mike Brown of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), who led the team that

found

Eris, would later style himself as the "man who killed Pluto", while deGrasse Tyson would

later jokingly quip that he had "driven the getaway car".

The finds spurred the International Astronomical Union to set up a committee tasked with

defining just what constituted a planet, with the aim of putting a final draft proposal before

members at the IAU's 2006 General Assembly in Prague.

Under a radical early plan, the number of planets would have increased from nine to 12,

seeing Pluto and its moon Charon recognised as a twin planet, and Ceres and Eris granted entry

to the exclusive club. But the idea met with opposition.

12/11/2015 Why is Pluto no longer a planet? BBC

News

http://www.bbc.com/news/scienceenvironment33462184

3/13

What happened next?

The discussions in Prague during August 2006 were intense, but a new version of a planetary

definition gradually took shape. On 24 August, the last day of the assembly, members voted to

adopt a new resolution outlining criteria for naming a planet:

Pluto met the first two of the these criteria, but the last one proved pivotal. "Clearing the

neighbourhood" means that the planet has either "vacuumed up" or ejected other large objects in

its vicinity of space. In other words, it has achieved gravitational dominance.

Because Pluto shares its orbital neighbourhood with other icy Kuiper Belt Objects, the resolution

effectively stripped the distant world of a planetary designation it had held for some 76 years.

It was immediately relegated it to the distinct category of "dwarf planet", alongside the biggest

body in the asteroid belt, Ceres, and other large Kuiper Belt Objects such as Eris, Quaoar and

Sedna.

Commenting at the time, the IAU's president of planetary systems science Prof Iwan Williams

said: "By the end of the decade, we would have had 100 planets, and I think people would have

said 'my goodness, what a mess they made back in 2006'."

12/11/2015 Why is Pluto no longer a planet? BBC

News

http://www.bbc.com/news/scienceenvironment33462184

4/13

Was that the end of the matter?

In a word, no. Some experts immediately questioned the part of the definition about a planet

clearing its orbital neighbourhood.

This is because Earth shares its cosmic turf with more than 12,000 nearEarth

asteroids. Thus,

some have argued that Earth, Jupiter and other planets also fail to meet the IAU's 2006

definition.

Speaking just after the vote, Prof Alan Stern, chief scientist for the New Horizons mission, called

the outcome "an awful decision" and described the new definition as "internally inconsistent".

Prof Owen Gingerich of Harvard, who chaired the planet definition committee, revealed that

only

10% of the 2,700 scientists who had attended the 10day

meeting were present at the Pluto vote.

The low turnout

has been blamed on timing; the vote was held on the last day of the General

Assembly when many participants had left or were preparing to fly out from Prague.

The debate has rumbled on ever since, on television, in the pages of books and in public talks.

Most recently, Alan Stern challenged Neil deGrasse Tyson to a debate on the matter in 2014.

But the latter expert turned down the offer, stating: "I don't have opinions that I require other

people to have."

The flyby of Pluto is unlikely to provide any information relevant to a change in Pluto's status.

But it will bring into clear focus once more what is, and what isn't, meant by the term "planet".

Follow Paul on Twitter.

Set C

Five Years Later, Pluto's Planethood

Demotion Still Stirs Controversy

by Mike Wall, Space.com Senior Writer | August 24, 2011 12:00am ET

Reddit

Artist's impression of Pluto and Charon as seen from one of Pluto's

other moons.

Credit: David Aguilar/Center for Astrophysics

View full size image

Five years ago today, the solar system lost a planet.

On Aug. 24, 2006, Pluto — which had been known as the ninth planet since its 1930

discovery — was demoted to the newly created category of "dwarf planet."

The decision was controversial, rankling some scientists who disagreed with the

reasoning behind it. It also upset and confused many laypeople, who had regarded the

nine planets as permanent fixtures in the sky — key touchstones for their understanding

of the cosmos, and their place in it.

But Pluto's reclassification shows that our knowledge of the world around us is always

changing, that scientific truths aren't handed down from on high. And that reminder may

be the greatest legacy of the longstanding debate about Pluto's planet status.

"This debate shows people, especially kids, that science is always evolving, and it's

exciting," said planetary scientist Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution of

Washington, who hunts for faraway dwarf planets. "And you should get involved in

science, because there's a lot more to learn out there." [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

Pluto is not alone

When Pluto was discovered in 1930, it was viewed as an oddball, and that perception

stuck for the next six decades.

Pluto, after all, is much smaller than the eight "traditional" planets, and its highly

elliptical orbit is considerably out of whack with theirs. Pluto is also much farther away,

zooming around the sun at an average distance of 3.65 billion miles (5.87 billion

kilometers). [Infographic: Pluto, A Dwarf Planet Oddity]

But in the 1990s, astronomers started realizing that Pluto isn't such an oddball after all.

They began finding many other large objects in Pluto's domain, the ring of icy bodies

beyond Neptune known as the Kuiper Belt.

The new discoveries prompted some scientists to re-examine their basic understanding

of the solar system's structure, including the way they'd classified its large objects. Just

what should we call these icy, faraway bodies? If Pluto is a planet, then should they all

be planets, too?

This rethink really got a jump-start in 2005, when Caltech astronomer Mike

Brown announced the discovery of Eris, a Kuiper Belt object that seemed to be even

larger than Pluto. And shortly thereafter, the International Astronomical Union (IAU)

stepped in.

Artist's rendering of Eris, announced in July 2005 by Mike Brown of Caltech. It is more massive than Pluto.

The sun is in the background.

Credit: NASA/JPL/Caltech

View full size image

Pluto's demotion

In 2006, the IAU came up with the following official definition of "planet": A body that

circles the sun without being some other object's satellite, is large enough to be rounded

by its own gravity (but not so big that it begins to undergo nuclear fusion, like a star) and

has "cleared its neighborhood" of most other orbiting bodies.

Since Pluto shares the Kuiper Belt with lots of other big objects, it failed to meet the

third criterion and didn't make the cut. Instead, the IAU rebranded Pluto and Eris as

"dwarf planets." [Meet the Solar System's Dwarf Planets]

Some planetary scientists generally agreed with the new classification, saying that

Pluto, Eris and other big Kuiper Belt bodies don't belong in the same category as the

eight "original" planets. The faraway icy objects, they say, are just too different — in

their sizes, compositions, orbits and evolutionary histories.

"It's classification that matters. Classification is the first step toward understanding,"

Brown told SPACE.com. "If you mess up the most basic classification of the whole solar

system by not noticing the difference between the eight large planets and everything

else — if you miss that, you've kind of missed the solar system."

Further, the word "planet" is so fundamental, and so central to any attempt to teach the

public about the solar system, that defining it properly is crucial, Brown added.

"If you said that there are eight planets and then a kajillion dwarf planets, that's a pretty

good description of what the solar system's actually like," Brown said. "If you said,

'Wow, we've got this planetary system and there are 20,000 planets. Oh yeah, and eight

of them are significantly bigger than all the rest of them' — it's not a very useful

classification."

Dissent and disagreement

Other scientists, however, aren't at all happy with the IAU's planet definition, calling it

flawed and unscientific.

"I think the IAU really embarrassed themselves with this," said Alan Stern of the

Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. Stern leads NASA's New Horizons

mission, which is sending a spacecraft to study Pluto up close. "They created a problem

for themselves and for astronomy. It [the definition] created an unworkable algorithm for

deciding what's a planet and what's not." [Cosmic Definitions: What Is a Planet?]

Stern particularly objects to the "clearing your neighborhood" criterion.

"In no other branch of science am I familiar with something that absurd," Stern

told SPACE.com. "A river is a river, independent of whether there are other rivers

nearby. In science, we call things what they are based on their attributes, not what

they're next to."

Further, Stern said, the criterion sets different standards for planethood at different

distances from the sun. That's because the farther away a planet is from the sun, the

bigger it needs to be to clear its zone. If Earth circled the sun in Pluto's orbit, for

example, it wouldn't qualify for planethood in the IAU's eyes.

"I would say any definition that produces a result where Earth is not a planet under any

circumstance is immediately indicted as ridiculous, because one thing we all agree is a

planet is planet Earth," Stern said.

Stern doesn't have a problem with the term "dwarf planet." He just thinksdwarfs should

be deemed "true" planets like the terrestrial planets and gas giants. Excluding the

dwarfs from the official list amounts to an effort to keep the number of planets down to a

manageable size, Stern added.

"That's not a very scientific way of going about it, since we have countless numbers of

stars, galaxies, asteroids and everything else," Stern said.

Images of the dwarf planet Pluto taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope.

Credit: NASA, ESA, and M. Buie (Southwest Research Institute)

View full size image

A better understanding of the solar system

While scientists such as Brown and Stern may differ on the question of Pluto's

planethood, they agree that the last two decades have brought about a sea change in

our understanding of the solar system.

For example, we now know that the solar system's frigid outer reaches are packed full

of big, interesting objects. The first big Kuiper Belt body other than Pluto was discovered

just in 1992, but Brown said up to 2,000 or so dwarf planets might actually exist out

there.

And many more big objects may lurk even farther away. Right now, astronomers know

of one mysterious probable dwarf planet, called Sedna, from the region beyond the

Kuiper Belt. But that distant zone — which is very difficult to survey with today's

instruments — may harbor up to 20,000 dwarf planets, Brown said.

So Pluto is now known to be just one of many big, icy and quite diverse bodies orbiting

the sun from far away.

"We have gone from nearly complete ignorance about these sorts of bodies to an

incredible richness, and trying to understand how they function as little worlds of their

own," Brown said.

Stern voiced similar sentiments, stressing that recent finds are showing planets — dwarf

and otherwise, in our solar system and beyond — are fantastically diverse.

"That's what we're finding in planetary science, as a result of not just the Kuiper Belt but

also discoveries about extrasolar planets," Stern said. "There are planets that have

densities like balsa wood, and planets that are darker than coal, and hot Jupiters and

super-Earths. I suspect we're just scratching the surface of the diversity — both in the

Kuiper Belt and around other stars."

The debate over Pluto's planethood is a result of this vast increase in knowledge, this

revolution in how we view our cosmic neighborhood. And it serves as a reminder that

science is not an ironclad set of facts but rather a process, a way to learn as much as

possible about ourselves and our surroundings.

"It shows that we're constantly expanding our knowledge of the solar system and our

place in the universe," Sheppard told SPACE.com. "Science is always evolving, and

we're always discovering new things."