Word Format - Australian Research Council

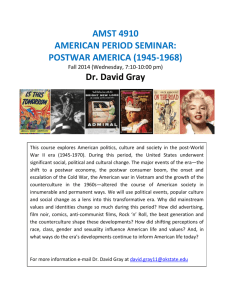

advertisement