File

advertisement

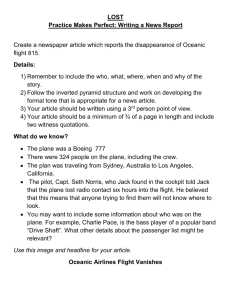

The Principles of Flight Fig 1 Have you ever found yourself wondering how planes fly? Or the difference between a glider and a plane? How aeroplanes, despite being far heavier than air remain suspended mid-air? Well, here is the answer to those questions; the ultimate paper aeroplane cheat book. Firstly, the main difference between a glider and a plane, is that gliders have three forces acting upon them and planes have 4. The force that gliders don’t have is thrust. Thrust is the force creating by a plane’s engines and propels the plane forward. This means that gliders, that have no engines, can never achieve sustained horizontal flight on a windless day. (Fig 1). The other three fundamental forces of flight that the glider and the powered plane share are lift, weight and drag. Lift is the force that pushes the plane above the ground. It is created by a plane or gliders wings. Weight is the force that brings the plane back to ground and drag is the force that slows the plane. (Fig 1). Air pressure is key to sustained flight. A high quality plane design will create areas of high air pressure under the wings. In a model plane or a powered plane, this is achieved using Bernoulli’s Principle. (Fig 2). Bernoulli’s Principle states that an increase in air velocity results in a drop of air pressure. This can be tested by holding a piece of paper length ways in front of your face. If you blow air onto the top side of the paper, the paper will almost achieve a horizontal state. In a regular plane (not made out of paper), the wing cross section will show that the bottom side is Fig 2 straight and the bottom side is curved. This means that the air is travelling faster over the top of the wing than the bottom of the wing. Going back to Bernoulli’s principle stating that higher velocity results in lower pressure, the wings rise because there is less air pressure above the plane then below it. This is also applicable to propellers. Fig 3 But while this information is key to achieving a working real plane design, its quiet useless in designing a paper plane. Keeping in mind that you can’t change the thickness of a paper plane wing, there is a different way to create sustained flight. To achieve a gliding paper plane, there has to be an equilibrium between the planes centre of gravity and its ‘centre of lift’. The best planes will have the ratio embedded in the design, but by folding the paper at the back or sides of the plane to create flaps, the centre of lift can be moved. Attached is a plane design. The Harrier (Fig 3), is an excellent design that employs these principles and adding flaps to it will only cause it to stall. The second, the Bulldog Dart (Fig 4, no instructions provided), can achieve an excellent glide by folding the outer side part of the wings inwards, increasing the amount of air pressure below the wings. Patrick Litchfield Fig 4 Harrier References Isaacs, Alan. A dictionary of physics. Oxford [England: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print. Macaulay, David. The way things work. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988. Print.