Adoption of RTE in Private Schools of Punjab

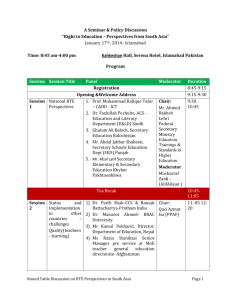

advertisement