Enter the Mononofu (lecture based on Totman, pp.107~113

advertisement

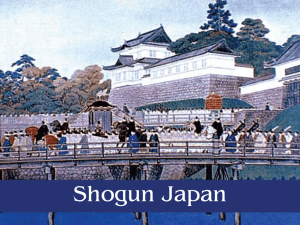

Enter the Mononofu (lecture based on Totman, pp.107~113, 92~97) We now begin to turn our attention to the rise of warrior class, the so-called bushi or samurai, as the dominant holders of political power on the Japanese archipelago. Before we do so, I want to revisit a note of caution: history does not unfold in tidy sequences, with clear-cut beginnings and ends. We’ve traced the rise of the ritsuryo state and its decline or attenuation, but the privileged elements that constituted the core of that political order—the imperial court, the aristocracy, powerful temples and shrines—did not disappear or simply cede power to the warriors. In fact, the rise of the warriors as significant power-holders is closely tied to the lingering power, wealth, and influence of the ritsuryo elite into the 13 th century. So, we will focus our attention on events and persons from the late-12th century, the processes behind those events and personalities both predated and outlived them. Change that prefigured the ascendance of the warriors: 1. Local Control Further comment on the weakening of central control (the main conceit of the imperial bureaucracy) seems unnecessary at this point, but the corresponding strengthening of local control requires note because the way it occurred contributed to other changes. During late Heian, as more and more rural localities were begin designated shoen, the holders of these new shoen confronted the need to identify their property, assess its productive capacity, and determine who would oversee the collection and delivery of rent, as well as maintain order. To do so, they conducted cadastral surveys that identified property boundaries and recorded information on acreage, yield, and resident population. This information was organized to form standard units of account known as myo. They put such myo under the control of local men of influence, whom they referred to as myoshu. The binding contractual document, a myoshu shiki, specified the rent that a myoshu was to forward in return for the holder’s recognition of his perquisites of office, any other land holdings he might claim, and such other aspects of his local standing as seemed appropriate. In the Kinai region, closest to the imperial capital, myoshu tended to be small proprietors whose assigned parcels of land averaged about 2.5 hectares (~6 acres), but in outlying regions, such as Kyushu and the Kanto, a myoshu holding might encompass 20 hectares (~50 acres) or more. Myoshu were thus people of local consequence whose status and function were sanctioned from above through the formation of shoen. Being local residents, they were in positions to open new land if it was available, discourage cultivators from absconding, recruit cultivators to till vacant land, and improve agronomic practice—in short, to improve productivity. Doing so became worthwhile for them once land rents were set, which assured that at least part of any future gains would stay with the locals. Moreover, periods of elite disorder, especially after 1150s (as we will see), provided these myoshu with opportunities to maneuver, and the more successful among them gradually became local magnates whose substantial residence compounds included outbuildings, storehouses, protective fences, in-house servants, and satellite servant households. During times of turmoil, these servants could function as fighting men for any myoshu who was inclinded toward military means, found he had little choice, or was serving as the retainer of a more powerful warrior leader in the vicinity. 2. Rural Production So, during the later Heian period operational control of the periphery (or hinterlands) gradually moved into the hands of myoshu or such other influential local figures as resident officials. As that occurred, more and more villagers found themselves encouraged or pressured to cultivate land more intensively, put nearby scraps of land to use, double crop in southerly regions, work more upland as dry field and orchard, and keep fields in production season after season. This intensified agronomy spurred the development of new hamlets and an increase in hamlet size. Local leaders welcomed the larger, more productive settlements as did villagers, for whom greater numbers mean greater security against bandits, marauding pirates and pillaging warriors during the increasingly frequent periods of turmoil. A number of changes to agronomic technique contributed to the slowly growing rural output. Regular tillage of more land was made possible by greater utilization of fertilizer material, mainly ashes, mulch, and manure. The last was becoming available because cavalry mounts were proliferating and draft animals were being used more widely. Improvements in iron-smelting technique provided more and better tools. Irrigation works expanded and water wheels for lifting stream flow to new paddy fields came into more common use. More and betteradapted varieties of crops were grown. Most notable was a more hardy variety of rice that came from the continent, probably in the later 12 th century, and which improved yield on inferior plots and during poor weather. With these changes, output rose and society grew, empowering more people to challenge the established ruling elite’s claim to a monopoly of power and privilege. A larger pie, with a growing proportion of it beyond the control of the old elite; those who control that new productivity had little incentive to allow the old elite to take control. 3. Continental influence In general terms, contacts with the Chinese continent had atrophied during the Heian period. As the example of the introduction of a new variety of rice suggests, however, contact did continue and some of it is relevant to our understanding of the transition to decentralized rule. Trade slowly developed between Japan and China, which Japan exporting large timbers, which were hauled from Kyushu to timber-starved China, and major import was Sung coins. They proved so convenient, despite official objections to their use, that during the 1220s resistance disappeared and their use became widespread. They also added to disorder in the realm, however, because the compactness and marvelous fungibility of coins, compared to most booty, encouraged piracy and banditry. Moreover, coins injected a new source of uncertainty into transactions and made the established elite more dependent on marketmen, who not only understood the mysteries of monetary process, but also were in position to provide, and hence to profit from trade. (A new source of wealth for a new strata). 4. Domestic trade For most of the Heian period, as we’ve noted, changes in domestic economic arrangements did not undercut elite control of exchange because the favored few remained the main consumers of non-essentials as well as the overseers of much production. By the 12th century, however, some trends were beginning to undermine that control, one being the emergence of organized groups of artisans and skilled provisioners that became known as za. Many Heian-period artisans functioned as house provisioners, directly providing goods and services to temples/shrine, aristocrats, and the imperial house itself. During the 12th century, which political tensions more acute, Heian in disarray, and provisioning evermore problematic, more and more of these elite institutions licensed specialized za to provide such diverse goods as reed mats, cloth, sewing needles, malt, lamp oil, charcoal, firewood, and lumber. The more successful of these provisioning groups expanded their roles as time passed, as when coins came into use, za members were optimally placed to exploit them. The za gradually acquired an array of new customers thanks the proliferation of well-to-do local magnates, including myoshu, resident official in district and provincial offices, and local warrior leaders, thereby reducing their dependence on the privileged few of Heian. During the decades around 1200, the formation of the Kamakura bakufu, with its country-wide network of subordinate peacekeepers, provided za with yet more customers. By the thirteenth century za members were peddling in the hinterland, controlling sectors of the market, functioning as money lenders, and lobbying among the favored few to promote their interests and fight their rivals. And they were doing so with minimal regard for courtly interests or sensibilities. 5. Demography Cumulatively, these trends meant that material production was rising; goods, services, and their providers were becoming more diverse, and exchange was growing more extensive. Contact among people across the realm was increasing, and villages were becoming larger, more numerous, and more densely settled. These developments appear to have altered the epidemiological enviroment, elevating small pox and measles pathogens to the status of endemic parasites of the human community. As such they gradually became, from the late 11th century onward, sources of habitual, non-lethal childhood disease rather than recurrent fatal epidemics of adulthood. This change in disease mortality smoothed over demographic trends, reducing the incidence of suddenly depopulated hamlets and abandoned land, and contributing to a renewal of overall population growth. For generations, however, that growth was slow, erratic, and regionally unbalanced. Much of it occurred in outlying area, main the Kanto, but also the northeast (Tohoku) and Kyushu, where more land was still reclaimable, where woodland offered more resources, and where the elite’s capacity to commandeer new production was weaker. Even there, however, population increase was slowed by a series of weather-related crop failures that may be attributed to global climate perturbations of the day. Most notable were crop failures in western Japan that severely weakened Taira opponents of Yoritomo’s eastern insurgency during the early 1180s and , later, crop failures that affected the realm more broadly around 1230 and 1260. Periodic demographic setbacks notwithstanding, the overall population did grow slowly, rising from 5 million or so around 700 to an estimated 7 million by 1200, and expanding more rapidly thereafter to perhaps 13 million by 1600. And because they slowly accelerating population growth was regionally imbalanced, it reduced over time the relative power of central Japan, the heartland of ritsuryo elite dominance, while strengthening the Kanto and helping sustain the breakaway potential of the northeast and Kyushu. Changes of the day were thus undermining the geographical basis of the ritsuryo order as well as its socioeconomic foundation. And fighting men were the ones most successfully turning these changes to advantage, in the process rising to political prominence. Rise of the Bushi The warrior class “emerged” long before the 13th century. Their rise, also, did not destroy the favored position of the ritsuryo elite. It did, however, constitute one of the many Heian-period developments that changed the way the classical aristocracy sustained itself. And it help lay the groundwork for eventual displacement of that aristocracy and its reduction to a symbolic remnant of old elegance whose residual political function was to help legitimate new ruling power. One facet of the bushi’s evolution from a force supporting Fujiwara regents and retired emperors to one destructive of them was a gradual change in the social composition and character of the warrior population itself. The rising bushi of Heian are usually envisioned as a two-tier populace: a small upper stratum of men with paternal imperial ancestors, and a vastly larger lower stratum commonly sprung from local magnates of one sort or another. Unlike the upper stratum, these lesser bushi had little reason to support the favored few. As generations passed, moreover, the distinction between high-born and lesser bushi blurred, and changing interests blurred the bushi leadership’s commitment to the established order. Already by the 1090s, the proliferating Minamoto seemed a threat to at least one Fujiwara observer, and from the 1160s onward Taira no Kiyomori’s incursions on aristocratic privilege severely eroded elite trust in bushi behavior. Then Minamoto no Yoritomo’s assertion of a permanent governing function for his bakufu government undermined the very basis for aristocratic faith in warriors as obedient subordinates. Unsurprisingly bushi repaid the growing aristocratic distrust and disdain with an elevated sense of their own worth. This changing mood was implicit in the emergence of the terms kuge and buke to distinguish the civil aristocrats of ritsuryo tradition from the powerful warrior houses affiliated with the bakufu. As the two came to view each other as separate and dissimilar social groups, moreover, warriors developed an accompanying rhetoric of selfesteem that increasingly defined buke as competent governing houses and kuge as cultured dandies of doubtful worth. Even more threatening to the old order were the many other warriors, particularly those of pedestrian ancestry, who had fared less well and who felt alienated not only from the old ritsuryo elite but also from its buke collaborators in the courtbakufu diarchy. Yoritomo’s victories during the 1180s, after all, were essentially the victories of one assemblage of warriors over rivals, most notably the Taira of Kiyomori but also diverse others situated all the way from Hakata to Hiraizumi. The victors acquired income rights, mainly in the form of shiki to shoen, many being gained at the expense of vanquished warriors. Subsequently the peacekeeping tasks of victors often put them at odds not only with the survivors of defeat but also with the many others who found avenues of advancement closed and means of support few. Those policing the peace referred to the many sorts who broke it as akuto, “evil bands,” and as decades passed, their numbers grew. By the later 13th century akuto had become a major element in civil disorder, a growing threat to diarchy and its beneficiaries. By 1250, the buke leaders of diarchy saw themselves not as dutiful servants of an esteemed aristocratic ruling class but as the operators of a political order that accepted, as one of its tasks, the obligation to assure the perquisites of a bothersome, often feckless, but useful populace of civil aristocrats. Within that bushi group, however, cohesion was weak and the new regime’s personnel foundation was eroding badly. In its cobbled-up form as diarchy, the old ritsuryo order and its privileged elite were in parlous condition, while many in the warrior class ere primed for further, more radical change. The blow by blow We are roughly familiar with the dominance of Fujiwara regents from x to y and the subsequent rise of retired, or cloistered emperors in the mid-11th century. In order to set the stage for the events of the clash between the Taira and Minamoto warrior clans, we need to return to the rise of retired emperors as the primary powerbrokers in the capital. The mature Go-Sanjo, if you recall, exploited mistakes and misfortunes of the regent Fujiwara no Yorimichi to become emperor in 1068, and he then moved energetically to reassert imperial authority and trim the power of the regent family. Despite his untimely death five years later, his vigorous 20-year-old son Shirakawa was able to ascend the throne and control affairs. He adroitly pitted Fujiwara leaders againsts each other, employed officials of other ancestries, and after retiring in 1086 enlarged in insei, or cloistered rule, structure and expanded the number of shoen it administered. He undertood major construction projects in Heian and so dominated political life during the early-12th century, that a senior Fujiwara figure declared: “the grandeur of the abdicated sovereign is equal to that of His Majesty, and at the present moment his abdicated sovereign is sole political master.” Subsequently Shirakawa’s son Toba took command, rapidly adding shoen to his holdings and using that fiscal foundation to sustain the splendor of imperial rule until his death. After his death, however, personal conflicts so poisoned the atmosphere in Heian that political life grew violent. The energetic retired emperor Go-Shirakawa lost control, and during the 1180s politics dissolved into all-out civil war, after which retired emperors never regained their pre-eminence. In an immediate and visible sense this rule by retired emperors constituted a vigorous reassertion of imperial governance, even though the shoen mechanism of fiscal control and the dominant role of the insei institution itself constitution subversions of ritsuryo governing procedure. It reaffirmed the authority of the imperial houseful and helped perpetuate the existing distribution of power and privilege. In other, more basic ways, however, insei rule witnessed considerable decay in risturyo governance. Most strikingly, the early-Heian arrangements in the northeast (Tohoku) grew shaky late in the Fujiwara heyday as rival magnates in the region jockeyed for position. In the 1050s warfare erupted, and during the 1080s a breakaway regional regime arose at Hiraizumi. For a century thereafter that entire region was lost to imperial rule. Closer to home, insei leaders were repeatedly challenged, as Fujiwara regents had been, by the armed warrior-monks of major temples, most notably Kofukuji at Nara and the great Tendai establishments of Enryakuji and Onjoji near Heian. Thus, in 1108 monks from the two temples marched into town to protest Shirakawa’s handling of a religious ritual, arriving armed with bows and arrows as well as protective armor. Wrote one distraught aristocrat: “It is possible that the mob now reaches several thousands. Truly, it is a frightening situation when the court has lost its authority, and [the palace] must be defended with all available might.” Furthermore, pirate gangs in the Insland Sea, which commonly consisted of local warriors and their henchmen, had been a sporadic source of trouble from Fujiwara regency times onward. By the 1130s they were such a severe meance, defying provincial authorities and directly threatening the capital, that the court bypassed its normal officials and placed a warrior, leading his own armed followers, in charge of their suppression. This courtly reliance on professional warriors points to the biggest problem of all: the rise of career military men as key players on the central political scene. As I explained last week, by the mid-12th century large numbers of men surnamed Minamoto and Taira held government office, drew income from shoen, and commanded bands of armed retainers. Increasingly they functioned as key military figures, being employed by civilian authorities to counter disruptive monastic groups and to suppress pirates and rebels who themselves commonly were bushi. More and more, Minamoto and Taira leaders also provided muscle in quarrels between aristocratic rivals. During the 1150s they played central roles in violent factional clashes at court, and in the outcome the ambitious and willful Taira no Kiyomori emerged as the pre-eminent warrior in the capital and the major ally of Go-Shirakawa. By the 1170s Kiyomori’s performance was resembling that of Fujiwara regents. His daughter become the consort of the young emperor, Takakura, who was himself born from a Taira mother, and in 1178 she gave birth to a boy who ascended the throne two years later as Antoku. By then Kiyomori had garnered high rank and office, assembled a grand array of shoen, and at his Rokuhara mansion on the ast side of Heian surrounded himself with all the amenities of the privileged life. By 1180, however, his bald ambition, rise to positions unprecedented for a buke chief, seizure of lands, and harsh punishment of any who resisted, finally even including Go-Shirakawa himself, had won him many enemies and alienated most old-line aristocrats. One sorely aggrieved figure was the imperial prince Mochihito, a son of GoShirakawa who believed that Kiyomori had denied him the throne. In 1180 he joined a plot to oust the Taira chief, and his call to arms reveals much about both the grievances people had and the rhetoric of political mobilization. Kiyomori and his followers, asserted Mochihito: Have incited rebellion and have overthrown the realm. They have caused the officials and the people to suffer, seizing and plundering the five inner provinces and the seven circuits. They have confined the ex-sovereign, exiled public officials, and inflicted death and banishment, drowning and imprisonment. They have robbed property and seized lands, usurped and bestowed offices. They have rewarded the unworthy and incriminated the innocent. They have apprehended and confined the prelates of the various temples and imprisoned student monks. They have requisitioned the silks and rice of Mount Hiei to be stored as provisions for a rebellion. They despoiled the graves of princes and cut off the head of one, defied the emperor and destroyed Buddhist Law in a manner unprecedented in history. Clearly such heinous behavior deserved punishment, and therefore, I, the second son of the ex-sovereign, in search of the ancient principles of Empror Tenmu, and following in the footsteps of Prince Shotoku, proclaim war against those who would usurp the throne and who would destroy Buddhist Law. We rely not on man’s efforts along but on the assistance of providence as well. If the temporal rulers, the Three Treasures, and the kami assist in our efforts, all the people everywhere must likewise wish to assist us immediately. Mochihito’s declaration, with its litany of complaints, its invocation of the cultural progenitor Shotoku and the warrior-emperor Tenmu, and its appeal to kami, Buddhas, and all who have grievances, was distributed to a number warrior leaders. The most notable recipient was Minamoto no Yoritomo, resident of Izu Peninsula, survivor of an earlier purge at the hands of the Taira, and mature head of the Seiwa Genji, a major Minamoto lineage that claimed descent from Emperor Seiwa. Numerous courtly, Buddhist, and bushi groups rallied to the insurgent cause, but in fact it fared poorly. Taira troops quickly hunted down and destroyed Mochihito and his supporters, in the process torching Onjoji, Todaiji, Kofukuji, and other temples for their involvement. Lamented one senior Fujiwara figure: All seven great temples [in Nara] are completely in ashes. This reflects the decline of both the Buddhist Law and the Imperial Law for the people in this world. I cannot find words, nor can I Find the characters to write what I feel. When I hear these things, my heart and soul feel like they have been butchered…I now see the destruction of our clan before my eyes. Even as that calamity was engulfing the Kinai, however, Yoritomo in the east was mobilizing forces. Whether he was driven by simple ambitious, a dire for revenge, or the conviction that Kiyomori would in any case destroy him because of his position as a senior Minamoto leader is unclear. Whatever moved him, he took to the field and in the outcome left a name for the ages. Cooperating awkwardly with both kinsmen and allies of the moment, YOritomo sent his armies westward to Kyoto and in a series of sharp battles drove the Taira back along the shores of the Inland Sea, defeating most of the remnants in northern Kyushu. The fighting of this Genpei War provided grist for the most celebrated war tales in Japanese history, fixing permanently in the popular imagination such battlefields as Ichinotani and Dannoura. By 1185 Kiyomori’s supporters were defeated, and by 1190 Yoritomo had eliminated rivals within his own family, most famously his younger brother Yoshitsune. He has also reduced the handsome political headquarters at Hiraizumi to ashes, in the process nullifying Tohoku autonomy for another century.