Student employability project - Intranet

advertisement

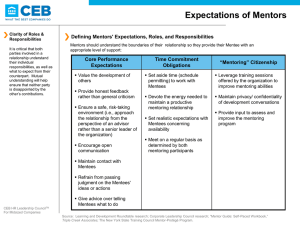

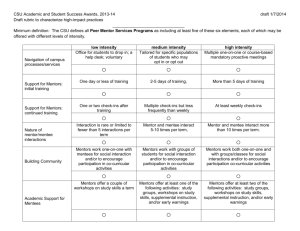

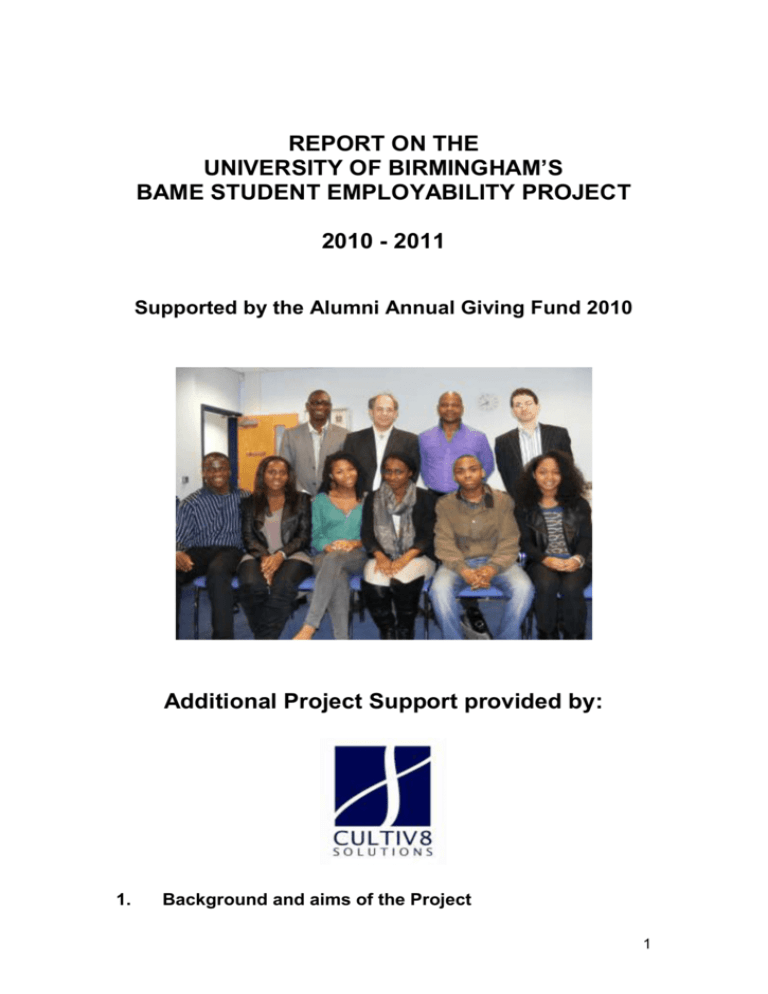

REPORT ON THE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM’S BAME STUDENT EMPLOYABILITY PROJECT 2010 - 2011 Supported by the Alumni Annual Giving Fund 2010 Additional Project Support provided by: 1. Background and aims of the Project 1 1.1. BACKGROUND The Equality Act 2010 places a duty on universities to monitor student outcomes by ethnicity, publish that information and take action to rectify any evident disadvantage. Around 28% of all students at the University of Birmingham are from a Black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) background. This figure includes international students. Outside London this is the largest percentage population of BAME students at a Russell Group university. BAME students appear to be attracted to the University of Birmingham. However, data suggests that generally BAME students are less likely to stay after the first year, gain a first or upper second class degree, complete their degree or gain a fulltime job after graduation. Annual reviews of the University’s ethnicity data have indicated that generally Black, Asian and ethnic minority students are not as successful as their white counterparts in finding full time work after graduation. For example, in 2006/7 52.8% of BAME and 58.6% white students gained full-time employment and in 2007/8 the percentages were 54.2 and 58.7 respectively. BAME students were almost twice as likely to be unemployed (in 2007/8 9.9% as against 5.6%). The BAME Employability Project was conceived as a direct, positive response to what appeared to be a disadvantage experienced by BAME students. This initiative was funded by a one-off donation of £4,000 from the Alumni Annual Giving fund 1.2. WHY AN INITIATIVE FOR BAME STUDENTS? As indicated in the introduction, BAME students are less likely to gain full time employment after graduation. This is not particular to the University of Birmingham but is a higher education sector issue. Bird (1996)1 adds that not only do Black graduates have greater difficulty gaining employment than their white counterparts, they also gain inferior jobs. Research (Reay 1998, 2009)2suggests that students who are the first in their family to gain a university place are less likely to understand, 1 Bird J.( 1996) Black Student in Higher Education: Rhetoric and Realities, OUP, Milton Keynes 2 Reay D. (1998) ‘Always knowing’ and ‘never being sure’: familial and institutional habituses and higher education choice. Journal of Education Policy, 13:4, 519-529 2 and have easy access to, the taken -for -granted assumptions about how best to assimilate into university life. It may take these students time to gain the student support and other networks that other students have knowledge of. This may have an impact on the outcomes of the university experience. According to Bird(1996)3 BAME students in elite higher education institutions are more likely to experience feelings of isolation; to experience being a ‘fish out of water’ and to consciously recognise being in a minority. Those who have researched BAME success (Rhamie and Hallam 2002)4 have suggested that important in success is the availability of positive role models, spaces for students to relax together and a relevant, representative and inclusive curriculum. HEA)5 commissioned research on the variable degree attainment of BAME groups and called upon HEIs to investigate the varied and uneven dimension of student experiences and how that impacts on student progression. Universities, they suggest, should have a much clearer insight into what impacts on BAME success. Positive action is legal under the Equality Act 2010 and allows organisations the freedom to use targeted initiatives where they recognised a protected group my be under-represented or underperforming in comparison with the wider community. Reay D. Crozier G. and Clayton J. (2009) ‘Strangers in Paradise? Working Class Students in Elite Universities’. Sociology 43 :6 3 Bird J.( 1996) Black Student in Higher Education: Rhetoric and Realities, OUP, Milton Keynes 4 Rhamie J.and Hallam S.(2002) An Investigation into African-Caribbean Success in the UK’ Race Ethnicity and Education, 5:2, 151-170 5 HEA( Higher Education Academy (2008) Ethnicity, Gender and Degree Attainment Project – A Final Report. ECU and HEA 5 Brennan J.and McGeevor P. (1987) The Employment of Graduates from Ethnic Minorities. London. Commission for Racial Equality in Bird J. (1996) Black Students in Higher Education: Rhetorics and Realities OUP Milton Keynes 3 1.3. AIMS The aims of the Project were to: Provide BAME focus groups to discover from the students themselves what, if any, were the issues/experiences/barriers that might negatively impact on the students’ experience and therefore contribute to any disadvantage in finding full time work. To consider a mentoring scheme as a possible response to any issues identified by students. Consider ways to build sustainability into the initiative Promote the positive impacts of such an intervention in support of BME students. 2. Development of the Project 2.1 PROGRESS October 2010 to March 2011 The Equality and Diversity Adviser for Students, Jane Tope commissioned the support of local businessman, Joel Graham-Blake to the project. Joel is an award-winning consultant and founder of Cultiv8 Solutions, a niche diversity development service for universities and the professional services sector. After analysing the responses from the focus groups they identified a need for a direct, interactive and personal development approach to employability support, different to initiatives conducted by other universities who, from the information available, seem to offer mentoring to all students who are interested. Through his networks, Joel recruited local BAME business and community based mentors onto the programme and he provided additional project support. 2.2 THE CHRONOLOGY October 2010 - 2 student focus groups were run engaging with 40 BAME students. 4 - An evening social event was held for both students and mentors to introduce and induct them into the Project - 12 mentors were individually interviewed and recruited. - 25 students were interviewed and given 30 minutes to explain why they felt they could benefit from the Project. - 18 students were accepted on the Project and carefully matched to mentors who best reflected their interests and background. - Support materials, such as the bespoke mentor and mentee handbooks which included how the Project would be monitored and supported were created and disseminated to both mentors and mentees. November 2010 – March 2011 - Each mentor and mentee was requested to meet at least once per month, and were encouraged to keep in touch weekly through email / telephone. - Contact by the Equality and Diversity Adviser for Students and the external consultant was made with the mentors and mentees to ensure they felt supported, to monitor progress and deal with any difficulties that arose. Generally, during this time both mentees and mentors needed very little intervention to enable them to progress their relationships. March - 2.3 End of Project consultation and social event with mentors and mentees. The feedback from students and mentors was elicited by a series of open-ended informal question and answer session. In attendance were 10 students and 7 mentors. Some gave their feedback via email. THE ISSUES identified by the students (general and specific to the Project’s aims): Lack of BAME role models at the University for students to connect with. Although there has been much research on the benefits, or otherwise of BAME role models for students, the students on this Project highlighted the lack of visible BAME role models as having a negative impact on their self confidence. 5 Feelings of isolation i.e. being visibly and culturally in a minority on their course. Where students were very clearly in the minority they felt that it was more difficult to find a voice, and be heard. Lack of networking/family connections. In many cases the students on the Project were the first from their family or community to go to university. See below for further discussion. Some students identified possible (perceived) racist comments from others around the University. For example, 3 students stated that when they looked for help by visiting their departmental administration, they felt that they were not immediately identified as students. Feelings of de-motivation in respect of job seeking because of the perceived lack of potential job opportunities within the current climate. The students felt that the current lack of job opportunities for graduates was likely to impact more on BAME students. Other issues that were highlighted included: Reliance on gaining support from Guild societies such as BEMA (Birmingham Ethnic Minorities Association) and friends from similar background rather than from staff. The support they consider useful included being able to relax with others from similar cultural/social backgrounds, values and attitudes to themselves. They also identified the importance of feeling integrated and settled at the beginning of their university life. Most students had supportive family structures, but stated they were the first to go to university. This made it more difficult to have familial discussions on the opportunities open to them and choice of career. Enthusiasm to ‘give back’ to the communities from which the students came and a commitment to making a difference in social terms. Bird (1994) draws on research by Brennan and McGeevor (1987:40)6 who state’ While the perceived benefits for white graduates tended to be greater in terms of individualistic goals, for black graduates they were greater for aims with a more social orientation’. Many of the students interviewed were already involved in voluntary / community / own businesses activities. Their choice of Birmingham was influenced by its reputation and students were attracted to a university situated in a multi- cultural city. 6 Brennan J.and McGeevor P. (1987) The Employment of Graduates from Ethnic Minorities. London. Commission for Racial Equality in Bird J. (1996) Black Students in Higher Education: Rhetorics and Realities OUP Milton Keynes. 6 Some international students felt they might benefit from the mentoring scheme, but it was decided to keep the Project focussed on UK students initially because the scheme was being managed by a small team. 3. The outcomes of the Project 3.1 PROJECT ACHIEVEMENTS This six-month pilot programme with 18 students and 10 mentors achieved a positive number of results including: 1 student has applied to journalist college and for a bursary to enable this to happen, supported by their mentor. 1 student has been accepted and is starting in 2011. 1 student has decided to start their own business again supported by their mentor. 1 student has already embarked on a new social enterprise venture with his mentor. 2 students have changed career goals and are now aiming for a more senior job role than first anticipated. All students have highlighted an increase in their understanding of the world of work, increased confidence and an appreciation of what they can achieve. All students have stated they have been inspired and motivated by the Project and consequently value the investment provided by DARO A number of mentees have expressed interest in becoming mentors for new students. Here are a few examples of some of the comments from mentees: Cheyenne – ‘It was really good to be paired with such a supportive and enthusiastic mentor. She has been so helpful, pointing me in the right direction for help and resources for my future. It’s been great to have a neutral space to talk through my decisions. It’s not always that easy to do that with a family member’. Amita – ‘The mentoring scheme has offered me so many skills and developed me as a person; I would never have envisaged how much it has impacted on my life. I now know that I can achieve whatever I want to achieve with hard work and dedication.’ Olu – ‘I’ve learned so many things from my mentor, and he’s helped me hone my presentation skills. He gave me insight into some of the ‘tricks of the trade’ 7 and he even set me homework! I did it and found it useful. My mentor understands where I’m coming from’. Wendy – ‘My mentor has really helped me gain more confidence. I am working on my presentation skills with his help’. Paris – ‘Working with my mentor has helped me see what is possible. We are working on two projects at the moment. It’s very exciting.’ The only comment for improvement from mentees is that they would have liked to have come together as a group a couple of times during the Project to offer each other peer to peer support. OUTCOMES – Mentors 3.2 A network of enthusiastic mentors ahs been built up, all of whom are keen to work with the University in future. All mentors felt they have positively gained from their mentoring role by being able to support students in their future development and by learning more about what it means to be a University of Birmingham BAME student. In some cases, the students’ ideas were supported by, and enhanced, the mentors’ business development. Here are a few examples of some of the comments from the mentors: Peter - ''My relationship with my mentee gave me a real life insight into what young people really need to succeed. His personal drive and passion to overcome any obstacle, was so humbling. He represented the passion and ability that young people from BAME backgrounds possess and can offer employers. The programme exceeded my expectations and I will definitely be volunteering again next year!'' Tony – “This process has allowed me to become more reflective and analytical about my own approaches to work, whilst at the same time, offer the benefit of my experience and skill to my mentee”. Marverine – “My mentee was rather shy and nervous to begin with. But I found that the moment we focused on what she can do, she built up the selfconfidence to overcome the fear of things that she thought she could not do”. Rickie – “This wonderful programme has taught me how to listen and encourage others more, rather than just telling them!” The only criticism from mentors was that there was too much tracking paperwork on the mentoring relationships. They understood the importance of effective monitoring and evaluation but suggested that the programme could use social media and other online resources as a way of tracking progress. 8 3. Other outcomes As a result of this project, professional and sustainable training materials for mentors and mentees have been produced. These can be shared across the university and be used for similar future schemes and initiatives. Positive publicity in internal University communications, including the Guild’s Redbrick diversity supplement. Interest in the Project shown by other universities who are looking to support BAME students into employment. Profiles of the mentors on page 10. 4. The future of the Project After having such a successful pilot phase and given the evident need, as highlighted in the research, for such positive actions, it is felt that the programme should continue to help support the progress into employment of other BAME students. It is planned to continue with the Project in its current organisation as detailed below: Joel Graham-Blake has agreed to continue his association and input into the programme and has already recruited new mentors to bring to the Project Focus groups will take place in May 2011 in order to identify the next cohort of mentees. New mentees will be recruited and matched to mentors by the end of October 2011. A minimum of two peer to peer sessions for mentees will be integrated into the programme. The aim is to enhance the programme by becoming a specific link with graduate recruiters to help find available job opportunities for BAME mentees on the programme. There is a possibility of training all the mentees from this pilot programme in peer mentoring, so that they can act as supportive mentors for first year BAME students at the University. Data analysis indicates that BAME students are less likely to stay after the first year. Transition to university is a key stage for many BAME students. 9 This initial pilot year of the Project has been successful and therefore Student services will now continue to resource this work for another year (2011/12) and seek recurrent funding for future years. MENTORS’ PROFILES Marverine Cole – www.funfmedia.co.uk Marverine Cole has over 20 years presenting experience in broadcast television & radio including many midlands radio stations and Sky News. In 2008, Marverine set up her own corporate video production company, Funf Media. Gman – www.tabooenergydrink.co.uk Gauntie is the Chief Executive of Taboo Energy Drinks and the Director of event management company C.G Marketing. He is a well-known personality within local communities and has over 25 years experience in media. Rickie Josen – www.missjones.info Rickie is the Managing Director of Miss Jones Concierge – a global PA and admin assistant service. She is also the project manager for FutureChefs – a national initiative focused on youth development through food! Anthony Andrews – www.wmbusinessfutures.co.uk Anthony is a small business adviser / consultant. He is also the Community Development Manager for a not-for-profit organisation that helps local parishes, make a positive impact in local communities. Herman Stewart – www.hermanstewart.co.uk Herman Stewart Assoc CIPD is a Consultant, Trainer and Motivational Speaker in mentoring within primary and secondary education. His work has been recognised as “High Quality” by Ofsted. Raj Theper Raj is a Business Account Manager for Business Link and has substantial experience in develop enterprise and community development. Peter Morrison – www.solasconsulting.com Peter Morrison is the MD of Solas Consultants, a personal development and coaching service for professionals and business owners. He is the founder of Leaflog – a low carbon biomass fuel source that burns 3 times longer than coal and has twice been awarded the prestigious title of British Inventor of the Year. 10 Matthew Broomhead – www.c4ucoaching.com. Matthew uses has over fifteen years practical experience (in corporate, non-profit and public sector) with professional qualifications in training and coaching. He is also a distributor for a utilities company and a member of the CIPD. 11