laparoscopy a veritable tool in modern practice iye hospital experience

advertisement

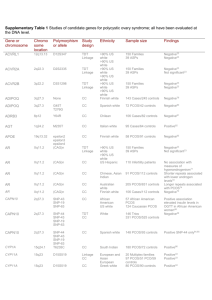

LAPAROSCOPY: A VERITABLE TOOL IN MODERN PRACTICE. IYE HOSPITAL EXPERIENCE *Kupolati K.S; Saka Folasade; Orji Emeka CASE REVIEW INTRODUCTION Modern practice needs a wide range of skill, knowledge, competence to remain useful to a wide range of patients. The advent of Laparoscopy has expanded our diagnostic and therapeutic options as shown in the following case presentations. CASE I. A 27yr- old housewife presented with 6yrs history of secondary amenorrhoea and primary infertility. Got married 8yrs ago. Occasionally takes primolut N with normal withdrawal bleeding. Examination showed a young woman with normal female contour. No breast milk discharge. Hormonal profile showed a high LH, normal FSH, low Prolactin, normal Insulin, low Progesterone and subnormal estrogen level. Transvaginal scan showed bilateral polycystic ovaries with poor EC. IYE HOSPITAL SCAN UNIT POLYCYSTIC OVARIAN DISEASE NECKLACE APPREARANCE OF FOLLICLES DEMONSTRATING PCOS. She had laparoscopic ovarian drilling bilaterally. OVARIAN DRILLING DURING LAPAROSCOPY Laparoscopic dye test showed bilateral fimbrial blockage with adhesions. Laparoscopic Adhesiolysis and Fimbrioplasty was done. Hysteroscopic tubal cannulation was successful. Chromotubation confirmed bilateral spillage. Her normal menses resumed 18days after ovarian drilling. POST OVARIAN DRILLING (LAP & TVS VIEW) Ovulation protocols was commenced based on her measured ovarian reserve volume after the second normal menses. FIGURE I: SAME OVARY WITH FOLLICLES DURING NEXT CYCLE See below her folliculometry pattern: CYCLE DAY RIGHT OVARY LEFT OVARY F1 F2 10 12.4mm 11.2mm No Follicles 12 16.0mm 15.0mm 13 19.1mm 16.8mm 14 23.0mm 21.5mm 15 24.5mm 24.5mm 16 23.9mmm 22.8mm OVULATION CONFIRMED 17 5.6mm 9.9mm EC 5.3mm 7.1mm 8.2mm 8.8mm 10.0mm 10.1mm 10.9mm The patient had intrauterine insemination with the washed sperm of the husband who had oligoasthenospermia. The patient got pregnant at first trial. EARLY CYEISIS CASE 2 A 23yr- old undergraduate was referred here with one week history of lower abdominal pains, backache and dysuria following a voluntary termination of pregnancy. On examination, she was very lethargic and pale. BP was 80/40mmHg Phase 5 sitting, her pulse was 109bpm, feeble. Pelvic scan confirmed a ruptured left tubal ectopic. She subsequently had laparoscopic salpingectomy. Note that a wide bore tube suction is of benefit in large haemoperitoneum. She was discharged after 48hrs of admission. = LARGE HAEMOPERITONEUM AT ENTRY TUBAL ECTOPIC IDENTIFIED CLEAN PERITONEUM AFTER SURGERY. DISCUSSIONS Laparoscopic surgery has evolved into a major treatment modality in treating patients with various surgical conditions as illustrated in the above two cases. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a condition in which the ovaries produce high amounts of androgens (male hormones), particularly testosterone. PCOS occurs in about 6% of women, and amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea (infrequent menses) is quite common. According to a 2002 study, nearly 30% of obese women with PCOS had amenorrhea. (The rate was lower--4.7%--in women with normal weight.) In PCOS, increased androgen production produces high LH levels and low FSH levels, so that follicles are prevented from producing a mature egg. Without egg production, the follicles swell with fluid and form into cysts. Every time an egg is trapped within the follicle, another cyst forms, so the ovary swells, sometimes reaching the size of a grapefruit. Without ovulation, progesterone is no longer produced, whereas oestrogen level remain normal The elevated levels of androgens (hyperandrogenism) can cause obesity, facial hair, and acne, although not all women with PCOS have such symptoms. Other male characteristics, such as deepening voice and clitoral enlargement, are rare. PCOS also poses a high risk for insulin resistance, particularly in women who are also obese. Insulin resistance is associated with diabetes type 2, in which insulin levels are normal or high but the body cannot use this hormone efficiently. About half of PCOS patients, in fact, also have diabetes. A woman is diagnosed with polycystic ovaries (as opposed to PCOS) if she has 12 or more follicles in at least 1 ovary, measuring 2-9 mm in diameter, or a total ovarian volume of greater than 10 cm3. Diagnostic criteria A 1990 expert conference sponsored by National Institute of Child Health and Human Disease (NICHD) of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS: Oligo-ovulation or anovulation manifested by oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea Hyperandrogenism (clinical evidence of androgen excess) or hyperandrogenemia (biochemical evidence of androgen excess) Exclusion of other disorders that can result in menstrual irregularity and hyperandrogenism In 2003, the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) recommended that at least 2 of the following 3 features are required for PCOS to be diagnosed. Oligo-ovulation or anovulation manifested as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea Hyperandrogenism (clinical evidence of androgen excess) or hyperandrogenemia (biochemical evidence of androgen excess) Polycystic ovaries (as defined on ultrasonography Treating Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Treatments for PCOS include the following: Ovarian drilling. This is definitely not the first line of management but recent observation in our centre has revealed its great value in amenorrhoea and infertility. It should be noted that the energy must not exceed 40W each lasting for about 4seconds. The number of holes will be determined by the ovarian volume. An average of six to 12 small holes in each ovary, is safe and effective for PCOS. It also reduces the risk for multiple pregnancies compared to fertility treatments. Other treatment modalities should be explored especially before ovarian drilling such as: Weight loss and a moderate exercise program. In women who are both obese and have PCOS, this approach has produced marked improvements in PCOS symptoms and in hormone levels. Metformin. Metformin (Glucophage) is commonly used to increase insulin levels and control blood sugar in people with type 2 diabetes. This agent and similar ones used in diabetes are showing great promise in reversing symptoms, reducing male hormones, and restoring regular menstrual cycles and ovulation in some women with PCOS. Studies suggest it might even be beneficial in nonobese women and in those who are not insulin resistant. Oral contraceptives. Oral contraceptives (OCs) may be used to restore regular periods in women who do not wish to become pregnant or who are not candidates for other approaches. It should be noted that OCs can be estrogen plus progestins or progestins alone. The progestins in any OCs should be newer ones, which are less apt to produce male characteristics. Fertility treatments. PCOS has typically been treated with clomiphene, even for women who do not want to conceive. This fertility drug blocks estrogen, which tricks the pituitary into producing the reproductive hormones FSH and LH. Gonadorelin (GnRH) administered in pulses, used alone or in combination with clomiphene, gonadotropins, or oral contraceptives, has been successful in some cases where clomiphene alone has failed. Women who want to become pregnant can take either clomiphene or superovulation agents (FSH agents or hMG) with or without assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Male-hormone blockers. Agents that block male hormone, such as flutamide, spironolactone, or finasteride, may be helpful alone or in combination with OCs to reduce male symptoms. They can cause birth defects in male offspring and so should be used by women who are also taking an OC. D-chiro-inositol. This natural substance, found in fruits and vegetables, improves insulin sensitivity and is under investigation Drugs that treat prolactin. Drugs, such as cabergoline or bromocriptine, which reduce hyperprolactinemia, (high levels of prolactin) may be useful for some women with PCOS. (They do not appear to be useful in women with PCOS and normal prolactin levels.) LAPAROSCOPY IN THE MANAGEMENT OF RUPTURED ECTOPIC PREGNANCY The teaching of performing laparoscopy in un-ruptured ectopic and open surgery in ruptured ectopic has been taken over. The skill and dexterity of most lap. Surgeons have improved greatly but it must be noted that it can only be attempted under the supervision of an experienced laparoscopic surgeon. In our practice, we use a wide-bore suction tube (minimum of 8mm) in a 10mm working port, a set pressure of about 14mm since most of the gas will be absorbed, and a good anaesthetist to give the patient robust monitoring. ECG monitoring is essential and perhaps mandatory. So far we have not had a single fatality in our centre. We prefer the use of Ringer’s Lactate or Normal saline to lyse clotted blood than Heparinized solution. The average admission time is 48hrs. SUMMARY Laparoscopic surgery has come of age and should be embraced by surgeons and Gynaecologists. Laparoscopy is easier on the patient because it uses a few very small incisions. For example, traditional "open surgery" on the abdomen usually requires a four- to five-inch incision through layers of skin and muscle. In laparoscopic surgery, the doctor usually makes two to three incisions that are about a half-inch long. The smaller incisions cause less damage to body tissue, organs, and muscles so that the patient can go home sooner. Depending on the kind of surgery, patients may be able to return home a few hours after the operation, or after a brief stay in the hospital. recovers quickly. Many people can return to work and their normal routine three to five days after surgery. In contrast, traditional laparotomy may require a person to limit daily activities for four to eight weeks. experiences fewer post-operative complications and less pain. The amount of discomfort varies with the kind of surgery. In most cases, however, patients feel little soreness from the incisions, which heal within a few days. Most need little or no pain medicine. has less scaring. The incisions for most kinds of laparoscopic surgery heal without noticeable scars. In laparoscopic surgery on a woman's reproductive system, for instance, one incision usually can be hidden in the belly button area. The others can be placed low in the abdomen, where any scars would be covered by a bikini. *DR KUPOLATI K.S is the Medical Director of Iye Hospital, challenge, Ibadan, Nigeria Life Member, Association of European endoscopic Surgeons Life Member, World Association of Laparoscopic surgeons Infertility Specialist and Laparoscopic Surgeon. Correspondence: Iye Hospital P.O Box 789, Dugbe, Ibadan. E-mail: iyehospital@yahoo.co.uk REFERENCES 1. Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, et al. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary Syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2745–9. 2. Stein IF, Leventhal ML. Amenorrhea associated with polycystic ovaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1935;29:181–91. 3. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 2004;19:41–7. 4. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004;81:19–25. 5. Carmina E, Koyama T, Chang L, et al. Does ethnicity influence the prevalence of adrenal hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome? Am J Obstet 6. Ferriman D, Gallway JD. Clinical Assessment of body hair growth in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1961;21: 1440–7. 7. Azziz R, Hincapie LA, Knochenhauer ES, Dewailly D, Fox L, Boots LR. Screening for 21-hydroxylase-deficient nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia among hyperandrogenic women: a prospective study. Fertil Steril 1999;72(5):915–25. 8. Dunaif A, Graf M, Mandeli J, Laumas V, Dobrjansky A. Characterization of groups of hyperandrogenic women with acanthosis nigricans, impaired glucose tolerance, and/or hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endrocrinol Metab 1987; 65:499 –507. 9. Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Dunaif A. Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:165–9. 10. Wild RA, Painter PC, Coulson PB, Carruth KB, Ranney GB. Lipoprotein lipid concentrations and cardiovascular risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1985;6l:946 –51. 11. Wild RA, Alaupovic P, Givens JR, Parker IJ. Lipoprotein abnormalities in hirsute women. II. Compensatory responses of insulin resistance and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate with obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 167:1813– 8. 12. Azziz R, Ehrmann D, Legro RS, et al. Troglitazone improves ovulation and hirsutism in the polycystic ovary syndrome: a multicenter, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:1626–32. 13. Welt CK, Taylor AE, Martin KA, et al. Serum inhibin B in polycystic ovary syndrome: regulation by insulin and luteinizing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:5559–65. 14. Goldzieher JW, Fariss B. The polycystic ovary. VII. Intractable uterine bleeding and endometrial hyperplasia possibly related to an extraovarian source of oestrogen. Acta Endocrinologica 1967;54:452–66. 15. Polson DW, Adams J, Wadsworth J, et al. Polycystic ovaries: a common finding in normal women. Lancet 1988;1:870–2. 16. Balen AH, Laven JS, Tan SL, et al. Ultrasound assessment of the polycystic ovary: international consensus definitions. Hum Reprod Update 2003;9:505–14. 17. Lobo RA. A disorder without identity: “HCA,” “PCO,” “PCOD,” “PCOS,” “SLS”. What are we to call it?! Fertil Steril 1995;63:1158–60. 18. Webber LJ, Stubbs S, Stark J, et al. Formation and early development of follicles in the polycystic ovary. Lancet 2003;362:1017–21. 19. Falsetti L, Galbignani E. Long-term treatment with the combination ethinylestradiol and cyproterone acetate in polycystic ovary syndrome. Contraception 1990;42:611–9. 20. Sanchez LA, Perez M, Centeno I, et al. Determining the time androgens and sex hormone-binding globulin take to return to baseline after discontinuation of oral contraceptives in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective study. Fertil Steril 2006 [Epub ahead of print].