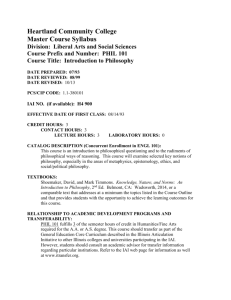

1NC

advertisement