EIPAshPondIncreasesFinal2_January52012

advertisement

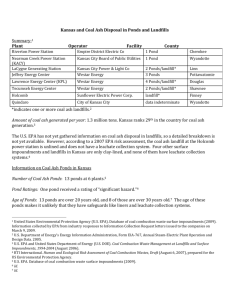

Disposal in Coal Ash Ponds Increases 9% in 2010 Environmental Integrity Project Analysis January 5, 2012 Just over three years ago, the embankment of a large impoundment at the TVA’s Kingston plant in Tennessee gave way, spilling a billion gallons of coal ash sludge onto surrounding property and into the Clinch River. Yet the most recent data from the U.S. Toxics Release Inventory show that disposal in these big ponds was higher in 2010 than it has been since 2007, the year before the TVA spill. Meanwhile, EPA’s proposal to set standards for safe disposal – which included a plan to close down ash ponds within five years – has gone nowhere. Federal “right to know” laws include a requirement that power companies report by volume the toxic chemicals that are contained in the ash and other coal combustion wastes that are dumped in surface impoundments (or ponds) every year. In 2010, power plants reported using ponds to dispose of wastes containing 112.8 million pounds of toxic metals or metal compounds, a category that includes arsenic, chromium, lead, and other pollutants that are hazardous in small concentrations and difficult to remove from the environment once released. That reflects a nine percent increase in pond disposal since 2009, and is higher than the total reported in 2008 (See Table A)1. The concentration of arsenic or other metals in ash or scrubber sludge can vary, based on the source of the coal and the effectiveness of air pollution control devices in removing these contaminants from stack gases. An increase in reported disposal volumes for these metals can mean either a rise in concentration of toxic metals in coal combustion waste, or an increase in the volume of waste containing these metals, or both. Just 20 facilities account for more than half (57 million pounds) of the toxic metals contained in power plant waste and disposed of in surface impoundments in 2010. Four of these are in Alabama, three in Georgia, and two in Missouri (see Table B). Ten states accounted for three quarters of total pond disposal in 2010, including (in rank order): Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, Indiana, North Dakota, Minnesota, and Michigan (See Table C). Most of these surface impoundments are unlined, which means that the toxins in the ash are more likely to seep through the bottom of these ponds and into groundwater or nearby rivers and creeks. The limited amount of monitoring data shows that this is already happening at many sites that have used surface impoundments for ash disposal for decades. Disposal in socalled “dry” landfills, especially those that are unlined, can also pose risks. The Maryland 1 Data from three Big Rivers facilities in Kentucky excluded from all years. See footnote in Table A for explanation. Department of the Environment closed one such facility in Ann Arundel County, Maryland, after its toxic leachate was found to contaminate nearby drinking water wells. But it can be especially hard to contain liquid wastes, as the volume and pressure increases over time. Surface impoundment walls can also erode over time, increasing the risk that the collapse of a dike may lead to catastrophic consequences. For example, two of the twenty facilities reporting the highest volume of pond disposal in 2010 have surface impoundments rated as “high hazard” during either EPA or state review. That means a major dam failure at these plants (Ghent in Kentucky and Bruce Mansfield in Pennsylvania) would result in “probable” loss of life, based on categorization by the Federal Emergency Management Administration. “Significant hazard” ratings were assigned to at least six of the “top twenty” plants in Table B, which means catastrophic failure would result in major economic loss or environmental damage: Barry (AL), Gaston (AL), Bowen (GA), Monroe (MI), JM Stuart (OH), and Gallatin (TN). Some of these facilities have multiple units, and TRI data is not detailed enough to determine whether disposal is occurring in those units with higher risk ratings. The fact that that a dam failure would be catastrophic does not mean that such an accident will happen, and some facilities have taken steps to strengthen dikes in the wake of the TVA spill. But the October 31, 2011, collapse of an embankment at the Oak Creek plant in Wisconsin, which tumbled construction equipment down its slopes and coal ash into Lake Michigan, is a reminder that these safety concerns cannot be taken for granted. That is why TVA, among other utilities, has announced plans to switch to dry disposal of such waste. EPA proposed in June of 2010 to require the closure of surface impoundments within five years. If the Agency manages to issue a final rule before the end of 2012, that ban would take effect at the end of 2017, a full nine years after the TVA spill. In view of the hazards these ash ponds present, that seems long enough. Sources: All data is based on reports submitted to the USEPA by the power industry, which is compiled on the Agency’s website at http://iaspub.epa.gov/triexplorer/tri_release.facility. Data may be sorted by facility or state for “metals and metal compounds.” For information about hazard rankings, see, “Summary Table for Impoundment Reports,” (XLS), USEPA (October 12, 2011), available online at: http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/industrial/special/fossil/surveys2/index.htm The risk rating for the Gallatin plant was assessed by TVA, and can be found by opening the link to, “Tennessee Valley Authority – Hazard Potential,” at: http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/industrial/special/fossil/surveys/index.htm#T TABLE A Trends in Total Land Disposal from Electric Utilities 2008-2010 Metals and Metal Compounds Parameter 2008 2009 2010 Landfills Surface Impoundments 239,964,348 215,776,057 244,016,735 Total 349,448,021 319,298,310 356,913,978 109,483,673 103,522,253 112,897,243 *United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2010 Toxic Release Inventory **Data from three Big Rivers facilities in Kentucky excluded for all years. These facilities reported disposing of more than 67 million pounds of metals in 2009, indicating a likely error in reporting. Therefore we have excluded these plants from our analysis. TABLE B Discharges of Toxic Metals to Surface Impoundments: Top 20 Facility County State Toxic Metals to Surface Impoundments (lbs) MILLER STEAM PLANT JEFFERSON AL SCHERER STEAM ELECTRIC GENERATING PLANT MONROE GA DETROIT EDISON MONROE POWER PLANT MONROE MI BOWEN STEAM ELECTRIC GENERATING PLANT BARTOW GA BIG CAJUN 2 POINTE COUPEE LA XCEL ENERGY SHERBURNE COUNTY GENERATING PLANT SHERBURNE MN COAL CREEK STATION MCLEAN ND KENTUCKY UTILITIES CO GHENT STATION CARROLL KY AMEREN MISSOURI LABADIE ENERGY CENTER FRANKLIN MO DYNEGY MIDWEST GENERATION INC BALDWIN ENERGY COMPLEX RANDOLPH IL JM STUART STATION ADAMS OH TRANSALTA CENTRALIA GENERATION / MINING LEWIS WA US TVA GALLATIN FOSSIL PLANT SUMNER TN GASTON STEAM PLANT SHELBY AL GORGAS STEAM PLANT WALKER AL WANSLEY STEAM ELECTRIC GENERATING PLANT HEARD GA GIBSON GENERATING STATION GIBSON IN ASSOCIATED ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE INC NEW MADRID POWER PLANT NEW MADRID MO BRUCE MANSFIELD POWER PLANT BEAVER PA BARRY STEAM PLANT MOBILE AL *United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2010 Toxic Release Inventory 5,205,430.90 5,002,506.80 4,093,461.01 4,016,417.20 3,236,897.00 3,044,913.10 2,958,061.30 2,646,451.90 2,559,562.50 2,461,016.00 2,444,326.10 2,432,827.40 2,322,065.00 2,300,046.40 2,224,502.50 2,184,803.50 2,153,538.80 2,118,000.00 1,979,263.00 1,906,342.20 TABLE C Discharges of Toxic Metals to Surface Impoundments: Top 10 Toxic Metals to Surface Impoundments (lbs) State Alabama 14,721,823.10 Georgia 13,842,179.40 Illinois 10,415,293.92 Kentucky 8,416,152.40 Missouri 7,764,312.84 Ohio 6,771,009.30 Indiana 5,947,077.65 North Dakota 5,559,315.13 Minnesota 4,903,986.87 Michigan 4,806,083.39 *United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2010 Toxic Release Inventory **Three Big Rivers facilities excluded from total discharges for Kentucky. See footnote in Table A for explanation.