04_rabies_diagnosis

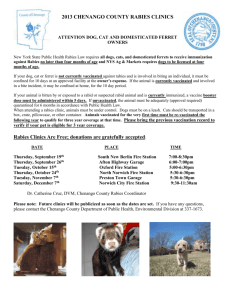

advertisement

Livestock Health, Management and Production › High Impact Diseases › Contagious diseases › Rabies Rabies Author: Prof Darryn Knobel Adapted from: Swanepoel, R. (2004). Rabies. In Infectious diseases of livestock, 2nd edition (J.A.W. Coetzer & R.C. Tustin, eds). Oxford University Press, Cape Town, pp. 1123-1182. DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Clinical signs and pathology Rabies should be suspected in cases of abnormal behaviour in animals, particularly when the affected animal comes from an area where the disease is known to be active, or when there is a history that suggests possible exposure to infection. Currently there are no reliable ante mortem tests for rabies infection. Confirmation of a diagnosis therefore relies on demonstrating the presence of the virus or antigen in the brain tissue post mortem. Animals with clinical signs suggestive of rabies, or displaying any progressive neurological disease in a rabies-endemic area, should be euthanized for examination. In certain circumstances where a dog has bitten humans or another animal/s, authorized persons (state veterinary officials) may confine the animal and keep it under observation for 10-14 days (the maximum time period measured between the presence of virus in salivary glands and the eventual onset of clinical signs). If the animal remains alive and healthy at the end of this period of observation, it can be concluded that the probability that the animal was infectious at the time that it inflicted the bite was very slight. Animals displaying signs of illness consistent with rabies during the period of observation must however be euthanized and brain samples submitted for laboratory examination. In cases where they are suspected of exposing humans to infection, wild animals, feral dogs, or stray dogs whose owner cannot be traced, should be euthanized for examination. Animals should be killed in such a manner as to avoid damaging the cranium. Protective clothing to be worn while collecting specimens should include gloves, an impermeable apron and a face mask or visor, and personnel should be immunized. The hippocampus is commonly used for the diagnosis of rabies, but the distribution of virus antigen varies and it should be routine to take tissue samples from a variety of sites in the brain. Brain specimens to be submitted for laboratory examination include 10– 20 mm3 blocks of cerebrum, cerebellum, hippocampus, medulla, thalamus and brain stem preserved in duplicate in 50 per cent glycerol-saline solution for virological examination and in ten per cent buffered formalin for histopathological examination. Where small animals are involved, half of the brain (sectioned sagittaly) may simply be placed in the glycerol-saline preservative and the other half in the formalin. If preservative is not available, specimens may be stored in empty containers on ice and submitted to the laboratory without delay. Adequate samples for making an accurate diagnosis may also be collected in wide-bore, plastic drinking straws by a method which obviates the need to skin the head and saw the cranium open: the occipital foramen is exposed with a knife and the sample is collected by inserting the straw through the foramen and pushing it with a slight twisting motion towards one of the eyes. The end of the straw containing the plug of brain tissue is cut off into the container with preservative. Occasionally, virus antigen or infectivity may be demonstrated in salivary glands and not brain, and it is recommended that samples of submaxillary salivary gland 1|Page Livestock Health, Management and Production › High Impact Diseases › Contagious diseases › Rabies should also be submitted in glycerol-saline and formalin preservatives. Specimen containers are sealed tightly and packed in sufficient absorbent material to soak up the entire liquid contents of the container. Laboratory confirmation Confirmation of a clinical diagnosis of rabies cannot be made by gross pathology or histology. The fluorescent antibody test (FAT) is the standard diagnostic test used to confirm a diagnosis. The FAT demonstrates the presence of rabies virus antigen in brain smears by means of immunofluorescence using antirabies fluorescein conjugate. The FAT takes only one to three hours to perform, and is of comparable sensitivity to mouse inoculation, with a concordance of 95 to 99 per cent between the two methods when the immunofluorescence test is performed by experienced investigators. The use of the FAT is limited by the costs of acquiring and maintaining a fluorescence microscope. A direct rapid immunohistochemical test (DRIT), employing a short formalin fixation of brain impression smears and requiring no specialized equipment, was shown to be 100% sensitive and specific when compared to the FAT. Supplementary tests include viral isolation in cell culture, mouse inoculation, polymerase chain reaction, and immunohistological tests. Histopathology on formalin-impregnated brain sections is not always informative for rabies infection but may help to exclude conditions in the differential diagnosis of rabies. Differential diagnosis Diseases which may be or have been, confused with rabies in southern Africa include distemper, infectious canine hepatitis, ehrlichiosis, cerebral babesiosis, toxoplasmosis, cerebral cysticerosis (caused by Taenia solium), tetanus, diminazine toxicity, pesticide (such as metaldehyde) and strychnine poisonings in dogs; cerebral theileriosis and babesiosis, thrombotic meningoencephalitis (caused by Haemophilus somnus) sporadic bovine encephalomyelitis (caused by Chlamydophila pecorum), botulism, lead, urea, chlorinated hydrocarbon and organophosphate poisonings, and cerebrocortical necrosis (caused by thiamine deficiency) in cattle; coenurus cerebralis (Taenia multiceps coenuriasis) in sheep; heartwater and a variety of plant poisonings (such as those caused by Homeria and Morea spp., Matricaria nigellifolia, Cestrum spp., Cynanchum spp., Dipcadi glauca) and the mycotoxicosis, diplodiosis, caused by the fungus Diplodia maydis in domestic ruminants; encephalomyelitis caused by equid herpesvirus 1 infection, tetanus, leukoencephalomalacia (caused by fumonisin B1 produced by the fungus Fusarium moniliforme) and poisoning by Senecio spp. in horses; and pesticide poisonings in all animals. 2|Page