Media:David_Lloyd_Final - Genomics and Bioinformatics

advertisement

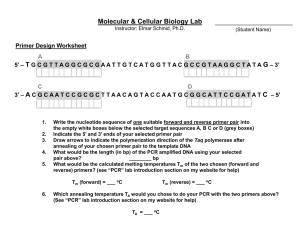

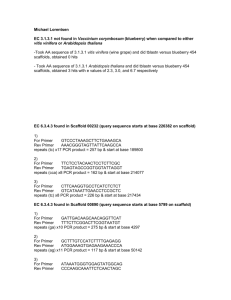

Possible genes affecting fruit size in Vaccinium corymbosum David Lloyd Abstract Fruit size is an economically important trait that, while extensively studied in other fruits, has received relatively little attention in Vaccinium corymbosum, the highbush blueberry. The purpose of this study was to identify and locate genes of potential importance to this trait in order to enable breeders to produce plants with larger fruit. To this end, I BLASTed genes that have been identified as affecting fruit size in other species against a set of scaffolds of the blueberry genome. This project was conducted as part of an undergraduate course at Davidson College. Introduction Larger fruit has the obvious advantage of higher yields. However, the issue of size is not limited to yield maximization, but also fulfills consumer preference for larger berries (Donahue et al. 2000). In species of the genus Solanum (tomatoes and their relatives), increase in fruit size quickly followed domestication. In fact, fruits from modern cultivars can reach masses up to one thousand times that of their wild ancestors (Cong et al., 2008) There are several possible mechanisms for production of larger fruit. In tomatoes, one can observe a marked difference in anatomy between smaller and larger fruit. Larger cultivars have a significantly increased number of locules (seed bearing compartments) compared to smaller domestic and wild varieties that have only two (Cong et al., 2008). Though there is no such variation in current blueberry cultivars, genes affecting floral organ variation in tomato may still be worth further investigation in blueberry. The majority of variation currently observable in blueberry is due to variations in cell number. Johnson et al. (2011) conducted an investigation of the correlations among various measurements of size. They found that fruit diameter is an accurate predictor of fruit mass with a linear relationship, and that cell number is an accurate predictor of fruit diameter with a logarithmic relationship. They also determined that average cell size did not demonstrate any correlation with fruit diameter and therefore mass. For this reason, the genes presented in this study which merit the most attention are those involved in cell cycle regulation and cell proliferation during floral and fruit development. In addition to cell cycle regulators, other genes have been shown to have an effect on mature fruit mass. In tomato, a form of invertase, TIV1, has been shown to significantly influence fruit size by regulation of sugar metabolism (Klann et al., 1996). In their study, Klann et al. determined that fruit which stored more sucrose by virtue of nonfunctional TIV1 were reduced in size by as much as 30%. This finding presents the possibility that fruit growth patterns can be manipulated and potentially increased my manipulation of the timing of TIV1 activity. As a wide range of processes can affect fruit size, there is no one pathway for the trait. However, Anastasiou et al. (2007) indicated the most important pathway involved is cell proliferation of fruit development (Figure 1). Figure 1. The fruit development pathway described by Anastasiou. (Reproduction of Figure 1 from Anasasiou et al., 2007). Methods I selected genes from the literature based on their observed effects in Vaccinium or other organisms. The genes chosen for analysis are shown in table 1. Gene fw2.2 ABP1 NtKIS1a CYC1 FAS fw1.1 fw1.2 fs1.1 fw1.3 fw7.1 fw7.2 fw2.3 fs8.1 fw3.1 fw9.1 fw4.1 TIVI pBI121 fw11.3 lcn11.1 ADH2 TG10 Reference (Cong et al., 2002; Frary et al., 2000; Grandillo et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2011; Lippman et al., 2001) (Cong et al., 2008) (Cong et al., 2008; Jasinski et al., 2002) (Cong et al., 2008) (Cong et al., 2008) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Grandillo et al., 1999) (Klann et al., 1996) (Klann et al., 1996) (Lippman et al., 2001) (Lippman et al., 2001) (Nesbitt et al., 2002) (Nesbitt et al., 2002) TG11 TG91 TG167 ANT ARF2 ARGOS BB ARL AN3 (Nesbitt et al., (Nesbitt et al., (Nesbitt et al., (Anastasiou et (Anastasiou et (Anastasiou et (Anastasiou et (Anastasiou et (Anastasiou et 2002) 2002) 2002) al., 2007) al., 2007) al., 2007) al., 2007) al., 2007) al., 2007) Table 1. The genes in this table have been implicated by the cited authors as affecting variations in fruit size in some fruiting plant. I searched for each of the above genes in the NCBI database. I selected the sequence from the organism most closely related to blueberry and saved those in FASTA format. In order to BLAST the sequences, I used a command line process in the Mac OS X terminal (Figure 2). The commands and steps given in the following figures will work on any Unix-based command line interface. A B C Figure 2. Note that “dalloyd” and “davidlloyd” will be replaced by the username and computer name of whomever is performing the task. The commands in (A) and (B) must be entered only once per login. Step (A) creates the database in which to operate, and step (B) sets up the BLAST commands. In (C) the actual blast command is entered. “tblastn” is used to blast a amino acid sequence and can be replaced with “blastn” to perform a nucleotide blast. “CYC1prot.txt” is the name of the plain text file containing the sequence to be blasted in FASTA format. Figure 3: A sample result for the BLAST process, this figure shows the output for the query performed in Figure 1. I considered hits to be significant if the E value was less than 110-4 (Figure 3). I submitted the scaffolds containing significant alignments to the SSR tool server at the blueberry genome portal (vaccinium.org, year). This online tool finds SSRs on the submitted scaffolds and the results are automatically compiled into a spreadsheet. I chose primers based first on their proximity and inclusion of my gene of interest, and then on the number of repeats of their SSR motif. A full list of my selected primer pairs for each gene can be found in Table 2. I submitted this report to the breeders at Washington State University. I and other members of the class also attempted to use a selection of tools from GenSas. However, due to poor results we discontinued use of that technique after one try. Results Gene Scaffold Location ABP1 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x20 327 108155 GTAACGAACGAACGAACGAAC ACAACCTTGCTTCCTTGATGAT PCR Product=206bp start:95084 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x19 GGGAGGAATTGAATGATGGTAA GGAACGACGAAGAACCTACCTT PCR Product=145bp start:89171 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x17 GATGGGGTTTGATGGATTCTAA CACCACACCACCAAACAACTAC PCR Product=161 start:31968 ADH2 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x31 1152 20288 AGCTCCACTAATCGGACTCAAG GGCACTTTCGTTTTCTGTTTTC PCR Product=284bp 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ag) x23 GGTAGGTAGGTAGGAGGTAGGAGG ACACGCTTTTAAGAATCACCGT PCR Product=126bp start:90446 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x10 GTCCCTGAAATCAAACAAGTCC AGCGTAGAGAATCGAACCTGAG PCR Product=221 start:1178 start: 25475 ANT 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (aaag) x4 162 33237 CCTAACGGTGTCAATTGGGTAT GCGATCTCTATTGAAATCCTGG PCR Product=166bp start: 31644 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x12 TGTGGTAGGTACGTACTCGTGG AAACATGCCCATAATGAAGTCC PCR Product=271bp start:107 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ag) x10 CGGAATCTTTCGTTATTGCTTC GTGGATGCAACTTAGGTGTCAA PCR Product=279bp start:38419 ARF2 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (aat) x13 51 50409 GATTTATGCACAACAAGGCTCA GACAGAAGAGTTAGCCAAGGGA PCR Product=237bp start: 27931 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ag) x11 GTTTGTGAACTCAGAGGCAGTG TATGTGACCCCAGTACACAAGC PCR Product=268bp start:24413 3) For Primer TGAAAGAAATCAACACCGACAG start:106486 Rev Primer Repeats (ac) x10 GGTTTTCCCTGATGTCTGCTAC PCR Product=197bp BB 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tg) x11 613 144727 CAGTTGTAGTTGGGGTTGGAAT TGTTTGCACAGATGTAAAAGGG PCR Product=149bp start: 96291 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ag) x11 AGTACGTATACACCCACCCCAG AATGACACCCAAACGCTTTACT PCR Product=157bp start:131191 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x13 GTGACCAGTGCACATTTTTCAT TTACTATCTGGGTGATGTGGGA PCR Product=210bp start:86304 CYC1 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ta) x10 277 33237 ATAACCTTGTAATTGCCGGATG ATCATAGGAATTGACACGACCC PCR Product=200bp start: 27802 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x16 TAGGTGTATGAACCCACGTGAA CTTTATTTCCCAGCTTCCAATG PCR Product=243bp start:5780 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x10 TGGTTCCTGTTTTGATCTTCCT AGTAGTGACAACCCAACCTCGT PCR Product=264bp start:72626 fw2.2 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ag) x12 1222 11597 GTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGA ATGTGAACCCAAAGTTACCAGG PCR Product=205bp start: 16660 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ct) x21 TAGGTGTATGAACCCACGTGAA CTTTATTTCCCAGCTTCCAATG PCR Product=287bp start:23817 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ct) x10 GTATGTCAACCACGGACAGTTG TGGGACACCAAATATACGTTCA PCR Product=272bp start:5445 fw7.2 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x17 704 125210 GATGTTGGGTTGATCGTACAAA CTTCCCAATACCAAAACCCTAA PCR Product=289bp start: 97640 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x10 GAGGGGGTGTGAATTTTGTCTA CTATTTTCCCTCTCTCCTCCGT PCR Product=265bp start:78950 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ct) x24 CCTATTTTTGGTGTTTTGTCCC ATCCTCCAAAAGTGTACACCCA PCR Product=271bp start:78053 pBI121 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x21 14 326508 ATGTGTTGCCACACTATTGCAT GGTTGTTGGTCTCTATCTTCCG PCR Product=300bp start: 290791 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (tc) x11 ACTTCAACCTTACCCCCTCATT TCAGGAGGAATAACCCAAATGT PCR Product=146bp start:333807 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x11 TGTGTGGAGTGGAGAGAGAAGA ACGGTAGCGAGACTACCCAATA PCR Product=249bp start:358798 TIV1 1) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x19 80 74980 GGTATCAACGAAAGCGTACCTC CGTCCGACTTCTAATAANACACG PCR Product=205bp start: 103562 2) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x11 AAGTTGGGCTTTACGGGATATT CAAGTGGAAAAACAAGTCCACA PCR Product=126bp start:59469 3) For Primer Rev Primer Repeats (ga) x15 GCTGAAAACACCACCAGTAACA TGCAAACGTAAACTTAAGCCCT PCR Product=237bp start:54986 Table 2. This table contains a list of the genes which produced significant alignments, their locations on the given scaffolds, and the three primer pairs I selected for each. GenSAS Results To test the protein BLAST function on GenSAS. I tested auxin-binding protein 1 (ABP1) from Zea mays. A tblastn query yielded a hit on scaffold 00327 with score=112 and E=2e-26. I then uploaded the entire scaffold to GenSAS as a plain text file. I selected Protein blast from the tools menu and created the task. I then received email confirmation that my task had started execution my task started at 14:57. I received an email at 15:25 saying that my task had failed. I submitted a detailed report of my experience with GenSAS to the developers, and it is my hope that the problem will be solved for future researchers. Discussion The results of my experiments are promising. It is my hope that the primer pairs I have provided will be useful to the breeders. My data will allow plant breeders to select individuals that express the desired trait (large fruit size) and to track these genes through the progeny. Hypothetically, one would subsequent generations which also expressed the large fruit phenotype to share alleles of the genes I examined with their large-fruited forbearers. The primer pairs that I have provided will allow the breeders to genotype progeny before they grow to maturity that could greatly speed the breeding process. Immature plants that have the ideal genotype for fruit size can be allowed to mature, reproduce and harvested. There is a chance that the data that are presented here will enable the development of new large-fruited cultivars. This would be a significant breakthrough for farmers who would be able to increase their yields without planting more land. Of course, it could also mean more blueberry mass per blueberry muffin, a possibility to which I doubt anyone would object. Acknowledgements Portions of the research for this paper were conducted jointly by the members of the spring 2013 section of BIO 343 taught by Dr. A. Malcolm Campbell, professor of biology at Davidson College. Genotype sequence data was generated and provided by the lab of Dr. Allan Brown of North Carolina State University. Dr. Jeannie Rowland of the USDA and Dr. Doreen Main of Washington State University were also instrumental in the execution of this research. This project was done in collaboration with Davidson College, NCSU, WSU, USDA and the David H. Murdock Research Institute. References Anastasiou, E., Lenhard, M. 2007. Growing up to one’s standard. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 10:63-69. Cong, B., Jiping, L., Tanksley, S.D. 2002. Natural alleles at a tomato fruit size quantitative trait locus differ by heterochronic regulatory mutations. PNAS. 99(21): 13606-13611. Cong, Bin., Barrero, L., Tanksley, S. 2008. Regulatory change in YABBY-like transcription factor led to evolution of extreme fruit size during tomato domestication. Nature Genetics. 40(6): 800-804. Donahue, D.W., Penoit, P.W., Lagasse, B.J., Buss, W.R. 2000. Consumer and instrumental evaluation of Maine wild blueberries for the fresh pack market. Postharvest Biological Technology. 19: 221-228. Frary, A., Nesbitt, T.C., Frary, A., Grandillo, S., Van Der Knaap, E., Cong, B., Liu, J., Meller, J., Elber, R., Alpert, K.B., Tanksley, S.D. 2000. fw2.2: A Quantitative Trait Locus Key to the Evolution of Tomato Fruit Size. Science. 289: 85-88. Grandillo, S., Ku, H.M., Tanksley, S.D. 1999. Identifying the loci responsible for natural variation in fruit size and shape in tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 99:978-987. Jasinski, S., Riou-Khamlichi, C., Roche, O., Perennes, C., Bergounioux, C., Glab, N. 2002. The CDK inhibitor NtKIS1a is involved in plant development, endoreduplication and restores normal development of cyclin D#;1-overexpressing plants. J. Cell Science. 115(5): 973982. Johnson, L., Malladi, A., NeSmith, S. 2011. Differences in Cell Number Facillitate Fruit Size Variation in Rabbiteye Blueberry Genotypes. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 136(1): 10-15. Klann, E., Hall, B., Bennett, A. 1996. Antisense Acid Invertase (TIV1) Gene Alters Souble Sugar Composition and Size in Transgenic Tomato Fruit. Plant Physiol. 112: 1321-1331. Lippman, Z., Tanksley, S.D. 2001. Dissecting the Genetic Pathway to Extreme Fruit Size in Tomato Using a Cross Between the Small-Fruited Wild Species Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium and L. esculentum var. Giant Heirloom. Genetics. 158: 413-422. Nesbitt, T.C., Tanksley, S.D. 2002. Comparative Sequencing in the Genus Lycopersicon: Implications for the Evolution of Fruit Size in the Domestication of Cultivated Tomatoes. Genetics. 162:365-379. Vaccinium.org. Genome Database for Vaccinium: SSR Server. 2011. http://www.vaccinium.org/node/5897.