LLAKES-Full-Paper

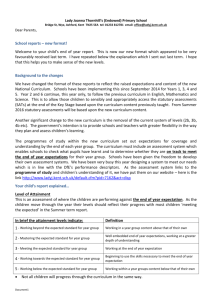

advertisement