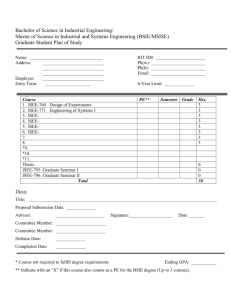

M.A. Graduate Student Handbook - Department of – Performance

advertisement