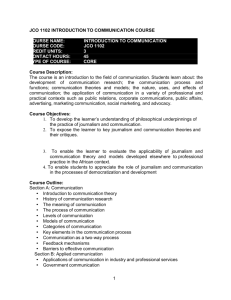

2013 Keynote Transcript - Columbia University Graduate School of

advertisement

Knight-Bagehot They say that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. I certainly use to think of myself as an old hand when it comes to America. American wife, kids with US passports, two of them at college here. I lived in New York for a while in the 80s and have been coming back regularly ever since. I also thought I knew all the nuances – and the jokes – about the whole British English/American English thing. We burgle whereas, for some reason which no doubt made sense at the time, you burglarize. You lead the world in the development of the internet, we on the other hand can actually pronounce it. Yes there are two Ts, ladies and gentlemen, and one of them falls in the middle – it’s not ‘innernet’, with that lamentable alveolar nasal, it’s the internet. Nor will you catch me out with your charmingly idiosyncratic use of the word ‘quite’. I know that here ‘quite good’ means well, really quite good, whereas back in Merrie Olde England, it means frankly pitiful. Except when it means the opposite. But I have been completely foxed by the meaning of the word to table. Back home, to ‘table’ something means to put it on the table, in other words to propose it. I’ve only just discovered that here it means to take something off the table – and I’m beginning to wonder whether any of the grand plans I’ve proposed at The Times are in fact being implemented or whether what I’ve actually asked my colleagues to do is to throw them into what you call the trash. No wonder they were nodding so enthusiastically. [1] I’ve also discovered the new verb ‘to reach out to’. There’s so much reaching out at The Times that I sometimes wonder if anything else ever happens there. To an English ear, ‘reaching out’ has a Bridge Over Troubled Water quality to it, it sounds like an act of heart-felt charity, you know comforting the widow and orphan, or trying to talk Arthur off the ledge. But I’ve finally discovered that in 2013 in New York City ‘to reach out to’ someone essentially means to send them an email. * * * It’s a real privilege to join you to celebrate the success of the Knight-Bagehot Fellowship. Business has been one of the few areas of journalism where we’ve seen fresh investment and large-scale new job opportunities over the past decade. But business and finance journalism have still been subject to many of the other pressures which are playing on the profession, in particular the arrival of on-all-the-time media and everything that goes with it – continuous news cycles, ever more platforms to service, a constant stream of new competitors, the compression of thinking time and reporting time. That last point is an important one. With a few honourable exceptions – some of my Times colleagues and of course Gillian Tett, who first suggested I give this speech this evening, are notable examples – too many of the major events and revelations of the past six tumultuous years have caught the world’s business journalists by surprise. [2] We need more and better enterprise journalism in business, finance and economics, as well as great beat reporting. We need more and deeper analysis and comment. The Knight-Bagehot Fellowship makes a significant contribution to all of these. I want to congratulate its board, its alumni and its many supporters for everything they do to raise the bar. What we do is valuable I’m going to spend a few minutes this evening talking about how we think about the future of journalism at The Times, and I’m going to frame my remarks with a few propositions. The first couldn’t be simpler. It is that what we and other serious news organisations do is valuable and will continue to be valued by discerning consumers irrespective of changes in technology and media consumption. For at least a decade this proposition has been under assault. People just don’t value high quality journalism enough to be prepared to pay for it, it was often said, so there’s no point trying to charge for it on the web. Or there’s a cohort effect. Older people do value it, but the young do not and, as the first die off and are replaced by the second, the market for quality journalism will inevitably collapse. Or maybe the fact that digital makes it so easy for anyone to make and distribute content means that anyone can and will become a journalist and the last handful of professional reporters will end up barricaded inside the last newsroom, like [3] the cast of The Walking Dead, surrounded by a swarming mass of citizen journalists armed with GoPros and iPhones. Now it’s true that quality journalism cannot rely on as much passing trade as it used to. Take international news on TV. When there were only three US broadcast networks, little or no cable competition and no internet, the news divisions could fight for audience share, turn a decent profit and still support a significant international newsgathering operation and broadcast a fair amount of international news. I ran the BBC news operation for much of the Tiananmen Square crisis and seeing the networks arrive in Beijing was like watching a series of US carrier groups sailing into port. Competition and fragmentation changed that. It meant a tougher fight for audiences, tougher economics and an understandable concentration on a more popular domestic and human-interest driven agenda. Investment in foreign bureaux declined dramatically – as it did at many newspapers across America and Europe. But we’re talking here at news aimed at mass audiences – audiences who were already known twenty-five and fifty years ago to prefer home news over international. The readers of The New York Times, of The Wall Street Journal or the FT, have always expected, indeed demanded high quality foreign coverage. There’s no reason to believe that that appetite is on the wane. For me, the fact that The Times has thirty bureaux outside of the U.S. isn’t a handicap, it’s a point of distinction and a valuable competitive advantage for the kind of readers we want to attract, as well as being an essential part of the mission of the Times. [4] When The Times announced plans to launch a pay model in 2011, members of the no-one-will-pay-for-quality-journalism school predicted that it would fail completely or only attract a handful of subscribers. We announced last week that we currently have over 725,000 digital-only subscribers, in addition to our more than a million print-and-digital subscribers. In fact, The New York Times has more paying customers today than at any previous point in its history – as well as the tens of millions of people who continue to access some of our journalism on the web and mobile for free every month. We certainly face challenges, but lack of underlying consumer demand is not one of them. So how about that age-related cohort effect? For anyone who enjoys a little light cultural pessimism, it’s a tempting notion – a generation of serious readers giving way to one which is more interested in celebrity and cat videos than macroeconomics. But the evidence doesn’t support it. If you said that relatively few millennials read The New York Times, you’d be perfectly right, and I’m sure the same is true of The Economist and The Guardian and Le Monde, but that was always the case. And we are not seeing a significant year-onyear increase in the age either of print or digital subscribers. In fact digital is bringing the average age down. And we should be careful about separating the two in our minds too much. Three quarters of our print subscribers authenticate for digital usage and they use print and digital seamlessly depending on convenience and time of day – print perhaps first thing in the morning, then a smart-phone on the [5] way into work, then a desktop or lap-top, with the tablet or the paper playing a bigger role in the evening and at the weekend. People often assume that we’re living through a one-way transition and that print will ultimately and inevitably fade away for all papers and magazines. They may be right, but they may not. I sometimes wonder whether it’s not what you could call the traditional desktop which is currently most at risk of being eclipsed by the phenomenal tilt towards mobile. That strong movement towards mobile certainly does raise questions for serious journalism. How do we get news of breadth and depth to consumers more and more of whose consumption is going to be on small screens and in relatively short sessions? It shouldn’t be impossible. A couple of thousand years ago, human beings created the codex, the small bound book with cut pages, precisely because it was more convenient to carry around and read than large scrolls. No one would suggest that the invention of the book made serious content harder to access. But the radical shift to mobile, and especially to smart phone, does mean profound challenges in design and user experience. Let me turn to the third threat – that professional journalism faces extinction because the people who used to be our readers and viewers will become our competitors. In my view, this view also falls victim to the substitution fallacy, the view that one kind of media inevitably gives way to another, whereas our experience is that media typically end up complementing each other, radio and the movies co-existing with TV, DVD, on demand viewing and so on. The democratisation of the means of production and distribution of journalism and other content is a good thing [6] and it challenges the profession in many ways. Newer entrants, whether specialists like Business Insider and Politico or broader like Huff Po and Buzzfeed, compete with fresh content perspectives and technical innovations, sometimes irritate us intensely by keying off our material, but nudge us also to our own experiments and breakthroughs, as well as broadening the diversity and choice available to the public. Citizen-reporting and other kinds of user generated content are also making a material difference to the way the world reports itself to itself. But it’s a false move in the chess game to conclude that we’re hurtling towards a future in which the skills and judgement of professional reporters and editors will no longer be needed. I happened to be in The Times newsroom when the Boston bombing story broke earlier this year. Over the next few days, more often than not the next development in the story was first flashed, not by any of the old or new journalistic providers, but by Twitter. And yet the problem with Twitter is you don’t just get the news, you get everything else as well: uncorroborated but potentially precious eye-witness testimony and citizen journalism, but also rumour, speculation, disinformation, propaganda, lies and general nuttiness. The idea that the world’s professional journalists could easily be replaced by a kind of Wikipedia of news, reported and curated by a global army of publicly-spirited amateurs is a rather noble one. But quite apart from issues of political and cultural bias, it turns out that what we face in a major unfolding hard news story is a vast, roiling sea of actuality with both truth and narrative often fiendishly hard to make out. [7] Jill Abramson, Dean Baquet and members of the masthead were in the newsroom pretty much round the clock that week, not to second-guess the mechanics of the coverage but because in the age of Twitter, classic editorial standards – about sources and fact-checking and balance and only going with something when you’re sure – really matter. The same is true – whatever you think of the underlying ethical and legal questions – about the way in which serious news providers like The Times, The Guardian, The Washington Post and others, have worked on stories originating from Wikileaks and Edward Snowden, investigating, substantiating, contextualising and assessing what it is in the public interest to publish and what it is not. We live in a time when great professional reporting and editing skills and great journalistic values aren’t obsolescent, they’re more important than ever. We need multiple revenue streams My second proposition this evening is that in the future we are going to need multiple, sustainable revenue streams to support serious journalism. Historically most owners saw newspapers and news broadcasts commercially as advertising platforms. The news itself might represent a civic good, but the best way of paying for it was by selling the attention of its consumers to advertisers. In the case of newspapers, this view typically implied a low cover price and a strategy of maximising distribution. The business was inevitably cyclical but the [8] margins of print advertising could be so high – 90% in the case of The Times even today – that that didn’t matter too much. Advertising remains really important for the Times. We have a new head of advertising, Meredith Kopit Levien, and a new determination to innovate in and develop our advertising business – and in particular to grow digital advertising. But we can never recapture the supply scarcity – and pricing power in advertising – which newspapers once enjoyed. We need circulation, now more than half the Times’ total revenue, and other significant sources of revenue, if we want to grow. In 2011, as you heard, we launched our digital pay model. The first plank of our new strategy is to develop additional pay offerings aimed at those who tell us they would certainly pay us something for Times journalism but less than the $200 or so which is our current lowest digital subscription – though we also intend to create enhanced offerings for those who tell us they would pay us more than the current most expensive subscription if we offered them the right additional features and services. We want, if you can bear the jargon, to exploit more of the demand curve. But we want to do it not just with cut-down or pumped-up versions of our current offering but with fresh expressions of our journalism that our newsroom and the rest of the company can really believe in, with their own integrity and appeal. One of the new ideas is a project with the working title of Need 2 Know. A mobile first product, it’s intended to offer users the perfect briefing not just on the news that’s already happened but on the stories up ahead that our editors already have their eye on, and to do it with its own voice. If you’ve caught the [9] ‘New York Today’ feature in the Metro section of our website, you’ll have an idea of what that voice could be. We’re also at work on a set of other offerings, ranging from opinion, one of the Times’ greatest strengths, to dining. The ability to exploit the same underlying intellectual property through multiple formats and time-windows is what made it possible for Hollywood to keep movies profitable, despite their colossal initial cost and despite the fragmentation of entertainment first by TV and subsequently by digital. News is too time-sensitive for many windows through time, but the development of multiple different expressions of our journalism, optimised for particular audiences and use-cases, aims to achieve the same effect. But we want to gather those different expressions under one core brand and one integrated journalistic operation on all platforms and in all territories. That’s why we decided this year to sell the Boston Globe. It’s a great newspaper with its own proud tradition, but a different brand, a different consumer proposition and a different business model. And it’s why a few weeks ago we renamed the International Herald Tribune the International New York Times. For the first time, not just the physical newspapers but every version of our website and of our apps will be under the same brand. Thirty years after The Times’ move to become a national newspaper, we want to explore what the international opportunity could be for us in terms of new subscribers and new advertising revenue We also want to explore what a fully [10] joined-up advertising sales force can achieve around the world with The New York Times brand and the interesting and valuable readers we attract both in digital and in print. And we’re developing other new revenues streams as well: o video, which from multimedia projects like the recent Game of Shark & Minnow from the South China Sea to newsfeeds to documentaries to features, offers the chance of deeper and rich audience involvement, as well as access to fresh advertising budgets; o conferences, where we are bringing The Times and IHT conference businesses together and significantly scaling them; o smart games, building out from our crossword franchise and its remarkable success as an independent digital subscription play; o and e-commerce. The revolution is only just getting started The third and last proposition I want to leave with tonight is that the revolution is only just getting started. Given the intensity of change we’ve seen in journalism over the past twenty years, and given some of the casualties, it’s easy to see why people might want to convince themselves that sometime soon the pace must slacken and a new steady state begin to emerge. That in business journalism, say, the market will shake out, the barriers to entryrise, some of the players consolidate and that a core of papers and channels and websites and apps will [11] remain made up of a mixture of old-stagers and newcomers, and that finally everyone can relax. One can’t rule anything out, but honestly I doubt it. Everything we know about digital and in particular about both private and professional consumption of digital suggests that actually we should expect the rate of change to accelerate. For incumbents everywhere that means that we have to do two things at once: to develop new services, revenue streams and ways of working at the same pace as digital insurgents, but also to maintain the commitment to seriousness and quality which has always marked us out and which remains our mission, indeed the only compelling argument for our existence. There are plenty of digital prognosticators out there that say that this twin task is impossible, that either we will end up lowering our standards or inevitably fall behind in the digital race. Let me finish by saying that we intend to prove them wrong and, at the New York Times Company, I believe we have the energy, the talent and the commitment to do just that. Thank you. [12]