Toxic row over cleaning water

advertisement

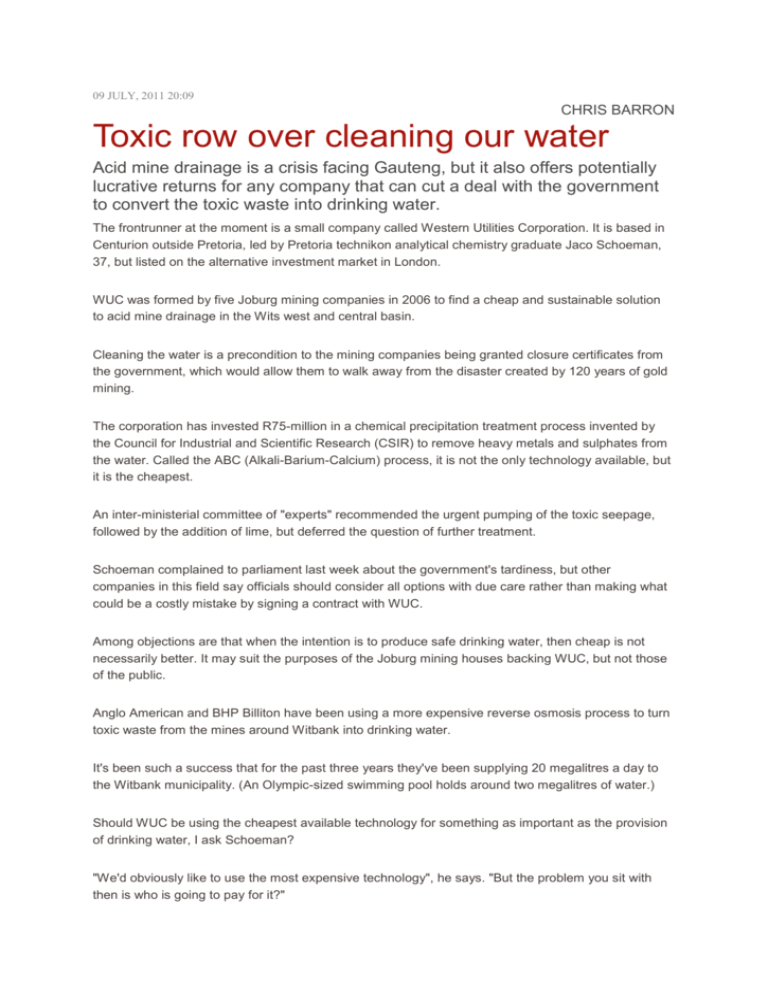

09 JULY, 2011 20:09 CHRIS BARRON Toxic row over cleaning our water Acid mine drainage is a crisis facing Gauteng, but it also offers potentially lucrative returns for any company that can cut a deal with the government to convert the toxic waste into drinking water. The frontrunner at the moment is a small company called Western Utilities Corporation. It is based in Centurion outside Pretoria, led by Pretoria technikon analytical chemistry graduate Jaco Schoeman, 37, but listed on the alternative investment market in London. WUC was formed by five Joburg mining companies in 2006 to find a cheap and sustainable solution to acid mine drainage in the Wits west and central basin. Cleaning the water is a precondition to the mining companies being granted closure certificates from the government, which would allow them to walk away from the disaster created by 120 years of gold mining. The corporation has invested R75-million in a chemical precipitation treatment process invented by the Council for Industrial and Scientific Research (CSIR) to remove heavy metals and sulphates from the water. Called the ABC (Alkali-Barium-Calcium) process, it is not the only technology available, but it is the cheapest. An inter-ministerial committee of "experts" recommended the urgent pumping of the toxic seepage, followed by the addition of lime, but deferred the question of further treatment. Schoeman complained to parliament last week about the government's tardiness, but other companies in this field say officials should consider all options with due care rather than making what could be a costly mistake by signing a contract with WUC. Among objections are that when the intention is to produce safe drinking water, then cheap is not necessarily better. It may suit the purposes of the Joburg mining houses backing WUC, but not those of the public. Anglo American and BHP Billiton have been using a more expensive reverse osmosis process to turn toxic waste from the mines around Witbank into drinking water. It's been such a success that for the past three years they've been supplying 20 megalitres a day to the Witbank municipality. (An Olympic-sized swimming pool holds around two megalitres of water.) Should WUC be using the cheapest available technology for something as important as the provision of drinking water, I ask Schoeman? "We'd obviously like to use the most expensive technology", he says. "But the problem you sit with then is who is going to pay for it?" He, and the rest of us, may be sitting with that problem anyway, say his critics. If and when the government signs the contract he's pushing for, WUC will do a deal with Rand Water to start supplying between 60 and 80 megalitres of drinking water a day. The aim is for the potable water to start being made available within 2½ years of the contract being signed. Schoeman says it will cost around R3 per cubic metre (as opposed to between R7 and R14 using reverse osmosis) to produce drinking water. But what if it ends up costing a lot more? Who will pay? Critics say that by this time Rand Water will be so committed it will have no option but to pay the extra amount itself. Which, of course, means the taxpayer will be stuck with the bill. The foreign shareholders who own WUC will reap dividends from what Rand Water pays to the company, meaning they will profit at the expense of South African taxpayers. Schoeman denies this will happen, because the costs will be capped. "That is a risk the funder is prepared to take," he says. His brief from the mines was to provide the most economically feasible, sustainable solution, he says. His critics argue there will be nothing sustainable about WUC's "solution" if the toxic and radioactive sludge left over from the cleaning process is dumped in mine tailings dams. Physicist Dr Richard Doyle, who is also CEO of Earth Metallurgical Solutions, says: "50% of their salts (dissolved metals) will end up on slimes dams." No it won't, says Schoeman. It will go into a "lined facility" which is "sealed off". Doyle says: "These linings degrade in time and eventually this gunk goes back into the water table. "It is not a sustainable solution to build bloody great waste dumps around the place." It will only be in that lined facility for eight years, says Schoeman. By which time WUC will have built a plant to recover the metals from that sludge. The recovery plant will process all the dissolved metals, Schoeman says, and the by-products from this process - such as gypsum - will be used to build houses, for example. What about the radioactive content? Schoeman says the sludge will not be radioactive "at all". "We've had radiation specialists conducting studies at every stage of the process - and on the sludge - and they declared the water fit for human consumption." Schoeman told parliament he was frustrated that the Department of Water Affairs had not yet signed a deal with WUC. The clock was ticking, he said, and the department needed to get moving. If it does not sign there will, of course, be a serious impact on WUC's share price. Schoeman says there will be no return on the R75-million invested. He says the investment was made "with the full knowledge of the Department of Water Affairs" and that there was "an agreement in principle" that government would give WUC the contract. Doyle says he is "deeply frustrated" that his own company, which has used the reverse osmosis process successfully, was not invited to make a presentation to parliament. He believes the stakes are so high it would be wrong for the government to opt for just one solution. "It would be absolute madness to commit such an important decision to a single technology without hedging both your technical and economic risks in selecting more than one technology," he says. If the department had been "more proactive", they would have been testing several technologies side by side for the past two years, he says, and would now be in a position to make a "qualified decision" on which technology or combination of technologies would be best. Doyle thinks the best way forward would be to allow several companies using different technologies to each contribute and then decide which is best. Schoeman says this would not be economically viable: the taxpayer would end up paying "significantly more for water at the end of the day". As for all the doubts about the process in which WUC has invested so much money, his answer is that this was the option recommended by the inter-ministerial committee of experts. What he does not say is that the CSIR, which will earn substantial royalties if the ABC process is used, was on that committee