Perfect Creme Brulee

advertisement

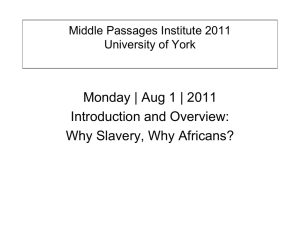

Perfect Creme Brulee Slow, gentle heat is the key to perfect custard, so for the best creme brulee, use chilled cream, a protective water bath, and a low oven temperature. c<:::::.>' BY GENE FREELAND · · y objective was si mple-find the perfect recipe for cla sic creme brQ!ee. My standards were h1gh-I wa·nted a custard that was light, firm, smooth, creamy, sweet, fragrant, and sl igh tly eggy, with a brown sugar crust that was both delicate and crisp. And, of course, making the process easy and quick was also a consideration. \ As I attempted to reach this elusive goal, trying some thirty-six variations al ong the way, I found that the process was one of exclusion, not inclusion. The fewest ingredients, fewest steps, a nd si mplest cooki ng techniques delivered the best results. M The Custard Probabl y the biggest challenge to making creme brillee is getting the texture of the custard right. In consulting dozens of recipes, I found a surprising number of options for the custard ingredients, in- I eluding variations on the eggs (either yolks only or whole eggs), the sugar (white, brown, or none at all), the flavorings (vanilla, rum, kirsch, various liqueurs, instant espresso, cinnamon, and grated nutmeg), and most importantly, the cream (heavy, whipping, or half-and-half). Further variations could be found in the cooking techniques, such as the temperature of the cream (from boiling to chilled) and whether to cook the custard on the stove or in the oven. I experimented with every possible variation, but found that the most crucial were the type of cream, the cooking time and temperature, and where thecustard was- cooked. (The results of my experiments with other ingredients are listed in "Searching for Perfect Creme Bn1lee," page 7.) I started with a simple, traditional creme bn1lee recipe that calls for two cups of heavy cream to be boiled for one minute, beaten into four egg yolks, returned to the fire over low flame (in a double n my search for the perfect creme brillee, I tried dozens of possible varia tions with the basic ingredients of cream, eggs, and sugar. The following list highlights some of my failures along the road to successfu l creme brillee. EXPERIMENT CONCLUSION Heavy cream used in custard Too rich for its own good Half-and-half used in custard Weak flavor and watery texture Whole eggs used in custard Too dense and firm Flavorings such as vanilla, cinnamon, nutmeg, and instant espresso Extracts and spices detract from the sweet cream and egg flavors Caramelized white sugar used in custard Flavor is burned and texture is grai ny Brown sugar used in custard Texture is grainy, flavor too sweet Salt added to the custard Odd and out of place Cornstarch added to custard cooked in double boiler May help prevent curdling, but leaves behind a grainy texture a nd makes custard very dense Yo-inch brown sugar topping Forms thick ba rrier that is too difficult to penetrate Powdered sugar used to dust buttered rameki ns Even small amounts make the custard too sweet 6 • COOK'S I LLUSTRATED • MARCH/APRIL 1995 boiler if desired), then stirred until nearl y boiling. The mixture is then poured in to a greased baking dish, chilled, covered with a thin layer of brown sugar, ca ramelized under the broiler, ch illed again, and served. I began by making separate versions of this recipe using all three types of cream, and cooking them in the oven, on top of the stove in a pan, and on top of the stove in a double boiler. The custard made with heavy cream, which contains between 36 and 40 percent f at, was way too rich; half-and-half, with between 10'/2 and 18 percent fat, made a watery custard. Whipping cream (sometimes called light whipping cream), w hich is between 30 and 36 percent fat, gave the custard the smooth, sweet, balanced flavor and texture I wanted. After this first set of tests, I al so dismissed cooking the custard on the stovetop in a saucepa n, since the results were so poor. The double boiler , was not much better, but I decided to try some \ variations before giving up on trus more forgiving method. I also decided to call Shirley Corriher, cooking teacher an d resident food science advisor for Cook's Illustrated, to discuss the results of my tests. Corriher started with some basic custard science. She explained that when egg yolks are heated, the bonds that hold together the proteins in the yolks begin to break. The proteins then unwind with their bonds sticking out, run into other unwound proteins, and bind together to form a three-dimensional mesh. This is what causes a custard to thicken. When a custard reaches 180 degrees, the proteins bond together so extensively that they form clumps and the eggs cu rdle-in effect, they become scrambled eggs. Because of this dynamic, t he speed with which you heat the custard mixtures is very important. "If the eggs are heated quickly, they won't thicken until well into the 170-degree range, sometimes just before 180 degrees, leaving little time for thickening before curdling," Corriher warned me. "If the eggs are heated slowly, though, thickening can start at 150 degrees and continue slowly as the custard heats past 160 and 170 degrees." S low, gentle heat, then, is the bestand probably the only-way to succeed with custards. Given that explanation, it was ob- vious that cooking the custard directly over heat was the worst possible way, as it heated the cus- tard most quickly. Custard science also explains why, in my next set of tests, I discovered that using up to a tablespoon of granulated suga r per egg yolk improved the baked custards to set like omel ets. Cooking the custards in a bain marie keeps their temperature f rom rising hen eggs are heated too quickly or with too hot a flame, above 212 degrees; this low the proteins in the eggs, denatured by the heat, bond together too extensively and form clumps (top), curdling the mixtem perature guarantees tha t ture. Proper heating technique and the presence of large sugar the custard approaches its set point slowly a nd therefore molecules, which inhibit bonding to some degree, cause the thickens gradually. At thi s denatured proteins to l ower temperature, the cusbond together properly tards cooked i n t h e wa ter (bottom) in a three-dibath were also silkier than mensional mesh that those baked in a 350-degree oven. As a f i nal refinement, I l owered t he oven temperat u re to 275 degrees and increased the cooking time to forty-five minutes. Even better. H ad I exhausted all the cu stard options? Not yet! I decided to f i ddle with th e tem peratu re of the cream. Un til now, I'd always boiled the cream for a min ute or so a nd then mi xed it in to the yolk-sugar mixture. Now, I tried my recipe with scalded cream, room tem perat u re cream, and ch illed the texture of the custard, while cornstarch made cream straight from the fri dge. I was pleasantly i t ex tremely dense, grain y, and sticky. surprised to find that the ch illed cream sample Corri her ex plained that sugar molecules are was richer, smoother, and more velvety than its very large- she calls them "Mack trucks"scalded or room temperature counterparts. and therefore come bet ween un wound egg When I mentioned this to Corriher, she was a proteins d urin g cooking, in effect blocking, at bit surprised. To my thinking, adding boiling or least tem- porarily, their attempts to bond. As my scalded cream to the yolks would raise their temtests con- firmed, adding sugar improves the peratu re too quickly. Corriher said this was cortexture of the custard. Cornstarch works in a si rect but that dairy products are usually scalded to milar fashion, but u nfortunately it also gives the custard an un- pleasant graininess. cause some of their proteins to u n wind and help promote thickening. After some thought, she said Cor riher also men ti o ned that stirri n g con stantl y, which is necessary to keep the heat evenly this was essential when ma king ice cream, which distri bu ted in a double boiler, where the heat all has a high proportion of m ilk. Unlike milk, howcomes from the bottom, makes thicken i ng more ever, high-fat cream does not have all that much difficult. As you stir, you actually break apart the protein, so the benefits of scalding or boiling the egg protei n s as they attempt to bond to each other. cream would be minor. Also, adding hot cream Whi le th i s is fine for a custard li ke creme anglaise certainl y raises the tem perature of the eggs very that should be thin enough to pou r, creme brfilee quickly. Si nce the secret to perfect creme brfilee has to be dense. At this poi nt, it seemed time to is very slow heat, using chi ll ed cream fit in with move on to the oven . the rest of my results . I first tried placing u ncooked and uncovered The Topping custards in a warm water bath, called a bain marie, in a col d oven, turned the heat to 250 de- While working on the custard variations, I also grees, and baked for eighty minutes. This first at- experimented with the caramelized sugar topping. tempt at oven-cooking was a disaster. The custard The first recipe I had tried called for a brow n did not set right, cooked unevenly, and was too sugar topping so thick that it formed a barrier difrun ny, and the brow n sugar toppings absorbed ficult to penetrate with a spoon . I soon realized moisture when they caramelized and turned into that two teaspoons of brown suga r per creme i ron plates. More lessons learned. brGhe gave the best coverage and depth for even, 1next tried covering and cooking the custard in controllable, and consisten t caramelization. a warm water bath in a preheated, 350-degree oven I also tested the relative merits of light and dark for fifteen minutes. When these custards had been brown sugar for the topping. On my first try, the cooked, chilled, topped and caramelized, chilled dark brown sugar topping burned quickly, was again, and finally served, I knew I was getting too hard, and didn't taste as good as the toppi ng close to reaching my goal. made with light brown sugar. However, the light As a final test, I compared u ncovered custards brown sugar topping was not perfect either, so I cooked in a bain marie with those cooked without decided to try d rying both light and dark brown a water bath i n 300-degree oven. Dry heat caused sugar for fifteen minutes in a 250-degree oven be- W ILLUSTRATION BY KAREN BARNES·WOOD RONSAVILLE HARLIN, INC. fore spri nkling them over the chilled custards. Pre-dryi ng the brown sugar significantly improved its taste, texture, and appearance w hen caramelized. Pre-dried dark brown sugar gave the topping a richer flavor that was superior to the light brown sugar topping, just the reverse of when the sugars were not pre-dried. It seems that drying brown sugar in the oven removes moisture as well as some of the lumps, which makes it easier to sprinkle and allows it to coat more evenly. Also, since the caramelization process involves melting the suga r and then evaporating some of i ts water, having less water i n the brown sugar before it is run u nder the broiler un doubtedly hel ps get the process going. A dried sugar topping needs less time under the broiler, so the dark brown sugar, with its richer flavor, can be used without the danger of burning or becoming too hard. PERFECT CREME BRULEE Serves 6 I tablespoon u nsalted bu tter, sof tened 6 large egg yolks, ch illed 6 tablespoons white sugar Jl/2 cups whipping cream, chilled 4 tablespoons dark brow n sugar I . Adjust oven rack to cen ter posi tion and heat oven to 275 degrees. Butter six '12-cup rameki ns or six 2h-cup custard cups and set them in a glass baking pan. 2. Whisk yolks in a medium bowl unti l slightly thickened. Add white sugar and whisk u ntil dissolved. Whisk in cream, then pour mixture into prepared ramekins. 3.Set baking dish on oven rack and pour warm water in to baking dish to come halfway up the ramekins. Bake uncovered un til custards are just barely set, about 45 minutes. 4. Rem ove baking pan from oven , leaving ramekins in the hot wa ter; cool to room temperature. Cover each ramekin with plastic wrap and refrigerate until chilled, at least 2 hou rs (can be covered and refrigerated overnight). 5. Whi le custards are cool i ng, spread brown sugar in a small baking pan; set in tu rned-off (but still warm) oven unti l sugar d ries, about 20 mi nutes. Transfer sugar to a small zipper-lock freezer bag; seal bag and crush suga r fi n e with a rolling pin. Store sugar in an airtight container until ready to top custards. 6. Adjust oven rack to the next-to-the-highest position and heat broiler. Remove chi lled ramekins from ref rigerator, uncover, and evenl y spread each with 2 teaspoons dried sugar. Set ramekins in a baking pan. Broil , watch i ng constantly and rota ti ng pa n for even cara melization, until toppings are brittle, 2 to 3 minutes, depending on heat intensity. 7. Ref rigerate creme brGJees tore-chill custard, about 30 minutes. Brown sugar toppi ng will start to deteriorate in abou t I hour. • Gene Freeland wri tes about food and art collecting from his home in Rancho Santa Fe, California. MARCH/A PR IL. 1 995 • COOK'S ILLUSTRATED • 7