Chapter 6 arts of resistance

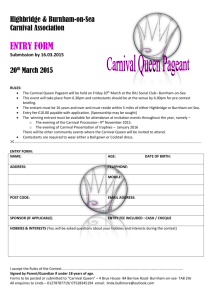

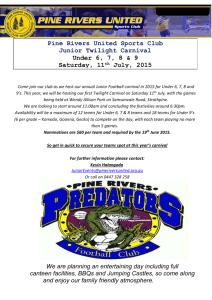

advertisement