here - Virgin Media

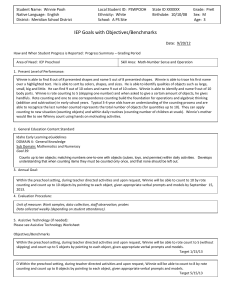

advertisement

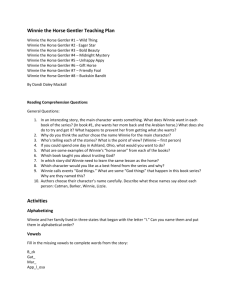

The greatest show on earth: Juliet Stevenson stars as Winnie in Samuel Beckett's Happy Days - the 'summit' part for any actress Stevenson is following in the footsteps of Peggy Ashcroft and Fiona Shaw but she isn’t daunted, the star tells Paul Taylor "Winnie is one of those parts, I believe," declared Peggy Ashcroft who took it on in 1975, "that actresses will want to play in the way that actors aim at Hamlet – a 'summit' part." Buried in scorched earth up to her waist in the first half and up to her neck in the second, the middle-aged housewife in Beckett's 1961 play Happy Days prattles away with dogged optimism to her mostly unseen and uncommunicative husband, Willie, in a loquacious attempt to stave off hysteria and despair. 1 It is, in the strict sense of term, an iconic role. An irritating woman, in some respects, but a heroic one, Winnie is a startling tragicomic symbol of human fortitude in the face of existential terror. And from Brenda Bruce and Madeleine Renaud (who starred in the English and French premières respectively) through to Billie Whitelaw (whom Beckett directed in 1979) to more recent exponents such as Rosaleen Linehan, Natasha Parry and Fiona Shaw, there has never, as Ashcroft predicted, been a shortage of dauntless actresses willing to suffer for their art by portraying her. Now joining their ranks is Juliet Stevenson, who is currently undergoing progressive entombment in Natalie Abrahami's new production at the Young Vic which opens to the press tonight. Stevenson leapt into the deep end of Beckett performance when she played the disembodied, dementedly jabbering Mouth in Not I for Katie Mitchell at the RSC in 1997. "Mouth is Winnie much further on down the road," she argues. But though it requires prodigious artistry to vomit forth that panic-stricken cascade of consciousness, the author himself conceded that Winnie is the more difficult role. Peter Hall has written that "Beckett's theatre is as much about mime and physical precision as it is about words". Between the piercing bell for waking and the bell for sleep, under a relentless sun that gives her no clue about the amount of time that has passed, Winnie struggles to pace her day and to ration her precious resources: the ritually inspected contents of her capacious handbag (toothbrush, lipstick, mirror – more ominously, a revolver) and her words – a dotty, lyrical monologue, threaded with refrains ("Oh yes, great mercies, great mercies"), continually interrupted thoughts and halfforgotten fragments of the "immortal" classics. The actress is buried in scorched earth up to her waist in the first half (Johan Persson) It demands from the actress an especially meticulous co-ordination of gesture and speech. Madeleine Renaud, renowned in that regard, declared that "I make no distinction between the words, the gestures, the objects... For me it's a whole; it's the inner state that counts", and the French choreographer Maurice Béjart claimed that he had learned to dance just by watching the eloquence of the actress's upper-body movements in the part. 2 By the second act, of course, Winnie can express herself only through the eyes and voice. The next step, before extinction, would be a plight horribly close to locked-in syndrome. How far does Winnie know that she is deluding herself? It's left to the actress to suggest the degree of uncertainty about this. Rosaleen Linehan, who has played the character both on stage in the 2001 Beckett on Film series, rabbited away with the hilarious would-be gentility of a ripe suburban Dublin matron. The flickers of doubt, alarm, and scorn were beautifully handled, the question of whether the character is predominantly foolish or courageous not answered too soon. You were put in mind of Alan Bennett's Talking Heads (particularly A Woman of No Importance), re-scored for Irish voice and pushed to an Absurdist extremity. But if you were to take Linehan's Winnie to a production of Happy Days, she would not consent to see her own predicament reflected in it. The reaction would be one of denial and disgust. This was in sharp contrast to the archly self-dramatising Winnie of Fiona Shaw who played her in the Lyttleton in vast landscape that seemed to have been devastated by global warming. The character here seemed to be theatrically aware that she was fending off her demons by putting on a sort of play. Her desperate dependence on an audience in the unlovely shape of her husband and her terror of the words running out were therefore remarkably vivid. This Winnie came over as a touch too knowing, though, as if, confronted by a production of Happy Days, she'd not only freely confess to a kinship with the protagonist but take the whole avant garde metaphor of gradual entombment in her stride. Of her own approach, Stevenson says that "I think that Winnie has to be a pre-conscious woman. She has such spirit and the capacity to be wry." (In one of her droller moments she asks, "How can one better magnify the Almighty than by sniggering with him at his little jokes, particularly the poorer ones?") "But I feel strongly that you have to journey into a different time and go on the same journey that this woman was on." Abrahami, who directed the first attempt at Not I by the now much-lauded Beckett exponent Lisa Dwan, points out that the dramatist likened Winnie to "a bird with oil on her feathers" and reveals that they have been playing around in rehearsal with the idea of the character as a creature of air and Willie as the force that roots her in the earth. "The $64,000 question," argues Stevenson, "is why Willie has made no attempt to rescue her and it's not one that Winnie can ask directly." So she asks it indirectly through her story of Mr and Mr Shower, the last human couple to stray that way, who gawp at her and make crassly insensitive remarks within earshot. Partly this pair are Beckett's way of poking fun at the audience, as when the man asks, "What's it meant to mean?" and his wife responds witheringly, "And you, she says, what's the idea of you, she says, what are you meant to mean?" They are also Winnie's oblique method of protesting: "Why doesn't he dig her out? he says – referring to you, my dear – what use is she to him like that?". She presents the incident as remembered reality. "But memory isn't an archive," says Stevenson, "She has adapted the story to what she needs it to be." 3 Irish author and playwright Samuel Beckett (Getty Images) Rehearsing Peggy Ashcroft in the role, Peter Hall recorded in his diary that "unless she is allowed to feel it all very strongly, she will never know what she is hiding". Hence her anxiety about visits from Beckett who did not really understand the work process an actor has to go through first before achieving the punctilious results he required. Stevenson understands Aschcroft completely. Her own rehearsal process has involved improvising with David Beames, who plays Willie, Winnie's recollections of their distant romantic days and a trip to Regent's Park where she got a brief taste of the heroine's panic and isolation when she was left by the production company buried in a heap of steaming compost. These days, the majority of anglophone actresses tackling the role adopt an Irish lilt (even Felicity Kendal did) to bring out the speech-rhythms inherent in the script. This new production will depart from that practice. Abrahami explains that Beckett ruthlessly excised from his early drafts any lines that tied the situation to Ireland or to a world in the wake of a nuclear attack– eg the news item Willie had read aloud about "aberrant rocket strikes Erin, eighty-three priests survive". The decision over Winnie's accent was made in the spirit of his quest for indeterminacy. The star and the director have thought the production through very carefully and, confirming Ashcroft's forecast about what the role would come to mean to actresses, Stevenson looks set to make this most terminally earthbound of protagonists once again take flight. 4