Philosophy Argument Paper Ethical Relativism

advertisement

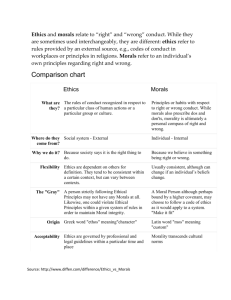

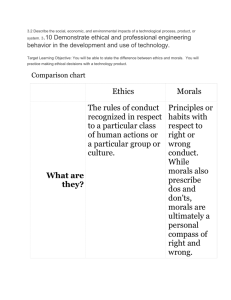

Caleb Leedy The Tri-Moral Model: Bridging the Gap Between Ethical Relativism and Universalism A great schism in Philosophy is the divide between ethical relativism and ethical objectivism; the former holds that the “moral rightness and wrongness of actions vary from society to society”1 and that “no absolute or objective moral standards…apply to all people everywhere,”2 while the latter maintains that “everyone has sufficient reasons to follow [the moral] law”3. Morality is thus the need for any true change—the “ought” that changes what “is” into “what it should be.” However, this limited definition of morality fails to account for the change in scope of moral issues. There is a wide range of moral issues and grouping the morality of killing people with the morality of eating meat is an unjust incorporation. Part of the problem when discussing moral issues is that universalists discuss moral issues of a vaster larger scale than ethical relativists. Universalists tend to argue about issues that can apply to everyone, like infanticide4, whereas relativists tend to base their argument on more personable issues, like the correct way to greet strangers5. Thus, there needs to be a differentiation between moral beliefs. There is a difference between the moral scope of infanticide and greeting others. To solve the problem of different degrees of moral importance, we need to characterize such moral beliefs into the Tri-Moral Model, having Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Moral sentiments. Therefore, by breaking morality into three different groups, morality is neither purely objective, nor purely relative; the degree to which morality needs be universally accepted is the degree to which moral standards violate fundamental rights. Primary morals are principles that must be true regardless of location and context. In 1. John Ladd, Ethical Relativism, qtd. in Louis P. Pojman A Critique of Ehical Relativism 2. Ibid. 3. Gilbert Harman, “Is There a Single True Morality” 4. James Rachels, The Elements of Moral Philosophy 5. William Graham Sumner, “Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Manners, Customs, Mores and Morals” Leedy 2 regards to the truth of moral principles, neither a correspondence test—a truth test that measures whether belief matches with reality—nor a coherence test—a truth test that measures the validity of an argument—will be used. The former will not be used because there is no physical representation of morality on earth. The latter will not be used because the coherence of morality would have to be tested against many different views of thinking—a scope too large for this paper. Rather, truth will be tested based on whether a statement, as Kessler eloquently describes, “works”6. Primary morals must be universal because universalism is the only framework of belief that works. There must be an objective standard to be able to change an “is” into an “ought.” Without universalism there is no impetus to be able to change anyone’s actions or belief. Santa Claus is just as moral as Bull Conner because the lack of an objective standard means that neither one of the figures is doing anything good or bad. Ethical relativism cannot apply to Primary Morals because ethical relativism cannot judge diametrically opposing ideas between cultures. If a mugger wants to kill his victim and the victim does not want to die, the ethical relativist cannot reconcile the two ideas because the sovereignty of ideas has been given to culture, to which anyone can appeal. As Pojman explains, having a subjective view of societal morality, that is an ethical relativistic view, could require that “Adolf Hitler was as moral as Gandhi, so long as each believed he was living by his chosen principles”7. The fundamental belief of ethical relativism, that that the morals of all cultures have value is absurd. Defining culture to be the beliefs of a collection of people, one could determine that a culture is the beliefs shared between an X amount of people. Because there is nothing unique about having X amount of people believe an idea rather than (X-1) amount of people, we could subtract people from the 6. Gary Kessler Voices of Wisdom 8th Edition 359 7. Louis P. Pojman “A Critique of Ethical Relativism” Leedy 3 group and still maintain the culture until we have two people. Any human being is prone to mistakes. Having two people agree does not create a correct argument. Even adding more people, while it might be more unlikely, does not guarantee that a correct idea will be agreed upon, especially since the additional person is as mistake prone as the people in the group. Therefore, ethical relativism cannot justify Primary Morals—there must be an objective standard from which to judge people. Only a Universalist approach can provide an objective standard from which a person’s decisions may be scrutinized. Without this moral weight ethics implodes, as there is no means to criticize other people.8 However, only Primary Morals are justified by the universalistic view of morals because ethical relativism is not self-contradictory with the Secondary and Tertiary Spheres of morality. Secondary Morals are principles that one can accept in another culture, but not in one’s own culture. Unlike Primary Morals where diametrically opposing ideas are annihilated, contrasting Secondary Morals can be tolerated, yet it would be difficult constantly be around someone with opposing Secondary Morals. One example of a Secondary Moral could be the killing of domestic dogs for food. While killing dogs for food may be acceptable in an eastern culture, I would have problems with someone killing my own dog here in the west. For Secondary Morals there is no universal law to which one must always follow. Instead, one must be conscious of the culture in which one is. Practically speaking, ethical relativism is an appropriate tool to use to justify a Secondary Moral because the stake of the issue is not as vital as a Primary Moral. Due to the fact that Secondary Morals are dependent on culture in which one is located, universalism is too overreaching because universalism requires that all culture accept 8. The absurdity of not being able to criticize another is more profound once one considers the fact that no one is justified in criticizing the one who is criticizing. Leedy 4 the same moral or morals, which need not apply to Secondary Morals because differences within the environment of a culture could produce different moral standards. While having ethical relativism as the core of a moral code is absurd because the lack of an objective standard forgoes any “ought” to change what a culture “is,” ethical relativism is needed in Secondary Morals because ethical decisions are based on culture. Tertiary Morals are principles that vary from culture to culture or within a culture, and can be accepted in a culture different than the culture of origin. For example different people have different opinions regarding pencil tapping. From experience I have found that the tapper generally regards pencil tapping as morally sound, while the listener believes that pencil tapping ought to end. The scope of pencil tapping is insignificant enough that not only is there a lack of universal law, but there is also the lack of a cultural law. Consequently, neither Primary nor Secondary Morals can properly be applied to the situation. Tertiary Morals are basically Secondary Morals applied on a smaller scale—the individual. Like Secondary Morals, Tertiary Morals are justified by ethical relativism. In fact, Tertiary Morals are just like Secondary Morals except that these principles can be carried out in foreign cultures without any consequences. While anyone can divide morality into many different parts the key to the Tri-Moral Model is answering the question: how does one determine to which category a moral principle belongs? For the Tri-Moral Model, the category that a moral principle aligns with is based upon the degree to which the moral principle violates fundamental rights. A fundamental right is a natural right that is, in the words of Thomas Jefferson, “self-evident”9 and “unalienable”10. If a moral principle deals with a right that is “self-evident” or “unalienable” then it is a Primary 9. “The United States Declaration of Independence” 10. Ibid. Leedy 5 Moral. If the moral principle does not violate a self-evident or inalienable right, but breaks a legal right within a culture, then the moral principle is a Secondary Moral. If a moral principle violates neither a self-evident or inalienable right, nor a legal right, yet still remains a moral principle then it is a Tertiary Principle. The primary difference between Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Morals is the scope of the fundamental rights—Primary Morals are morals that should be universal; Secondary Morals are morals that should be cultural; Tertiary Morals are morals that should be individual. It is important to understand that this paper simply argues for the existence of three categories of morality—Primary Morals, Secondary Morals, and Tertiary Morals—not where specific morals should be categorized. A main objection to the Tri-Moral Model is the fact that a relativist may insist that no universal moral exists, or the Universalist may claim the morals are purely universal. However, these objections can also be understood within the Tri-Moral Model. The relativist is simply claiming that all morals are Secondary and Tertiary, while the Universalist is claiming that all morals are Primary. This question regarding the location of specific morals is too broad; this paper does not address this issue. Instead this paper only asserts the existence of three classifications of morals—Primary Morals, Secondary Morals, and Tertiary Morals. Overall, the Tri-Moral Model, separating morality into Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary branches, accounts for the fact that morality is neither purely relative, nor purely objective. Understanding this model will hopefully reconcile the divide between universalism and ethical relativism. Leedy 6 Bibliography Harman, Gilbert. "Is There a Single True Morality?." In Explaining value and other essays in moral philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press ;, 2000. 77-100. Kessler, Gary E.. Voices of wisdom: a multicultural philosophy reader. 8th ed. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 1992. Ladd, John. Ethical relativism. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 1974. Pojman, Louis P.. Ethical theory: classical and contemporary readings. 2nd ed. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth Pub. Co., 1995. Rachels, James. The elements of moral philosophy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986. Sumner, William Graham. Folkways; A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and Morals.. New York: The New American library, 1960. United States Declaration of Independence. 1776