civil rights law outline

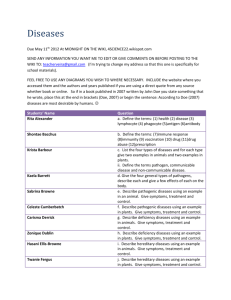

advertisement