Discussion Leader Summaries

advertisement

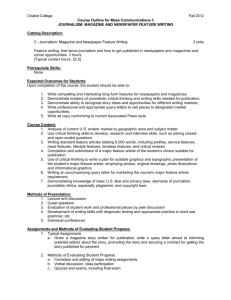

COM 750: ADVANCED MEDIA THEORY (FALL 2013) Sept. 26: Sociology of Journalism and News Decision-Making Discussion Leader Summaries By: Sindhu Manjesh Zelizer, B. (2004). Taking journalism seriously: News and the academy: Sage Publications, Inc. (Chapters 3 and 6 Distributed to Class). CHAPTER 3: Sociology and Journalism In this chapter, Zelizer outlines and expands upon the development of journalism as a discipline of study within the tradition of social scientific research. He posits that the focus on journalism was largely associated with sociology’s ascent in the academy. He starts by placing the study of journalism in the historical context of US academia – an exponential interest in journalism in the 1920, the explosion of the social sciences in the 1930s, the subsequent rise of communication schools, and the co-option of journalism by these schools as a sub-set area of study. Zelizer divides his inquiry into three waves: 1) Early Sociological Inquiry: Journalists as Sociological Beings 2) Mid-Period Sociological Inquiry: Organizational Studies of Journalism 3) Later Sociological Inquiry: Journalistic Institutions and Ideology. In each of these periods, his analysis is multi-layered, in that he approaches different aspects of the study of journalism scholarship. Before diving into these domains, he gives us an overview of the origins of sociology as a discipline and the motive of sociological inquiry. He acquaints us with the discipline’s functionalist and Marxist leanings and its cultural concerns (pp. 46). He states that “sociological inquiry positions its target of analysis squarely within the network of individuals engaged in patterned interaction in primarily complex settings.” (pp. 47) Next, Zelizer takes us through the growth of the sociology of journalism in the US, UK, nad Europe, touching upon important contributions in theory made by the Chicago School and the Frankfurt School and influential scholars such as Robert Park, Wilbur Schramm, Paul Lazarfeld, Joseph Klapper, and Todd Gitlin to name a few (pp. 48-51). Early Sociological Inquiry: Journalists as Sociological Beings In this section, Zelizer discusses different ways in which it was approached – as a practice, its setting in larger society, its political economy, and asks whether it is a craft or a profession. He further divides his study to encompass four areas: 1 1) 2) 3) 4) Gatekeeping, Social Control, and Selectivity Processes Occupational Studies: Values, Ethics, Roles, and Demographics Normative, Ritual, and Purposive Behavior Effects Research Gatekeeping, Social Control, and Selectivity Processes Here, the concept of journalists as ‘gatekeepers’ – as those capable of blocking, adding, and changing information – is discussed. He draws out attention to how gatekeeping can either be idiosyncratic and subjective, a result of collective thought processes, or a tool of knowledge control. He discusses the notion of social control in the newsroom as espoused by Warren Breed (1955), where in the issues of power and adherence in a social organization, peermotivated behaviour, and production power-play are highlighted. He then guides us to the seminal work of Johannes Galtung and Marie Ruge (1965) on gatekeeping, which gives us a set of 12 criteria of what constitutes ‘newsworthiness’ and what goes into the likelihood of a story making it to the headlines (pp.54). Occupational Studies: Values, Ethics, Roles, and Demographics In this sub-section Zelizer navigates the occupational settings in which journalists work, the impact of that on what they produce, ethics, and how the demographics of the journalistic community in a particular setting might affect the role of journalism in society (pp. 55-58). Interesting here is the point about the differences in role-perception of journalists across nationalities. Normative, Ritual, and Purposive Behavior Normative behaviour patterns of journalists, the rites and rituals by which they worked (based on culture-specific contexts), and the role of journalists as ‘social constructionists’, where they make meaning as opposed to consolidating influence are discussed in this section (pp.58-60) Effects Research This discussion focuses on this tradition’s origins in the US, uses and gratification research, and agenda setting theory (pp.60-62). Mid-Period Sociological Inquiry: Organizational Studies of Journalism According to Zelizer, this wave that progressed from the 1960s onwards looked toward broad organizational settings as a way to examine the patterns of interaction among journalists. The ethnography of workspaces and organizational theory are in focus here. News is explored as a manufactured organizational product (pp.63) and Edward J. Epstein’s ‘News from Nowhere’ (1973) – where he suggests that organizational and technical constraints managed the making of news – is cited (pp. 63). Later Sociological Inquiry: Journalistic Institutions and Ideology 2 Zelizer says that these studies located the force of ideological positioning outside journalism, where it worked in tandem with other institutions. “Journalists thus came to be increasingly considered agents of a dominant ideological order external to the news world itself.” (pp.69). He discusses scholarship around the institutions of journalism, the notions and role of ideology vis-à-vis journalism, Gramsci’s construct of hegemony with regard to journalists (as agents who secured agreement by consensus rather than by forced compliance), the Glasgow University Media Group’s contributions to the sociological inquiry of journalism (pp. 74), and the political economy of journalism with a discussion on Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman’s ‘Manufacturing Consent’ (1988). In conclusion, Zelizer proposes that sociological inquiry “reduced journalists to one kind of actor in one kind of environment. It was up to other disciplinary frames to complicate that picture.” (pp. 80) He moves on to exploring other scholarly prisms through which journalism has been studied. Discussion Questions: 1) Is journalism a discipline or practice? 2) Who is a journalist? 3) Should journalism be viewed as a verb or a noun? CHAPTER 6: Political Science and Journalism In this chapter, Zelizer invests himself and us in exploring the constructs of political science theory vis-à-vis the scholarship on journalism. He opens with a decided statement: “When compared with other scholarly views on journalism and journalistic practice, the perspective offered by most scholars in political science has been decidedly normative.” (pp. 145). He explains that this scholarship examines journalism through a vested interest in the political world and touches upon the concept of journalism as the government’s fourth estate. Key here are concepts of mediated democracy, mediacracy, mediated political realities, media politics, all derived from the assumption of interdependency between the political and journalistic worlds. Zelizer takes us back to the work of Walter Lippman (1914, 1922/1960, and 1925) and his concerns with the journalist’s role – he called upon them to act as experts in mediating the information that the wider public received. Citing Denis McQuail, (1987), Zelizer posits that this school of thought was pre-occupied by normative standards – how the world of journalism ought to operate in conjunction with certain political systems. Zelizer devotes a significant section of this chapter (pp. 146-150) to the evolution of political science research into journalism – from the study of government in ancient Greece, to Tocqueville’s formulations on the effect of the press on public opinion in France and America, to the “sound-bite age” of politics and journalism. Zelizer outlines three directions of research or typologies in political science scholarship on journalism: 3 1) The “smallest picture” – between a journalist and source. 2) The functioning of journalism’s intersections with the political world, taking into account actors and audiences. 3) Large-scale typologies of interaction, which attempted to describe possible operating traits for journalism under different political orders. In discussing journalistic models and roles through the prism of political science theory, Zelizer draws our attention to the three models of journalism in democratic systems that Schudson (1999) outlined (pp. 154): 1) The market model (in which journalists gave the public what it wanted). 2) The advocacy model (in which journalists transmitted political party perspectives). 3) The trustee model (in which journalists provided the news citizens needed to be informed participants in democracy). In discussing journalistic roles in this scholarship, Zelizer cites Bernard Cohen (1963), who established a typology that separated the journalist’s “neutral role” from the “participant role”. (pp.155) In subsequent sections, Zelizer explores the scholarship on freedom of expression (pp. 157), and the evolving ties of journalistic and democratic systems and how journalism affected democratic process (pp. 158 and 159). He then turns his attention towards scholarship on public or civic journalism (pp. 164-166) and how this is seen as a variant of trustee journalism discussed earlier. Finally, Zelizer discusses journalism’s large-scale relationship with its surrounding political system and the typologies of interaction between them (pp. 167). He devotes this section to a discussion about the ‘Four Theories of the Press’ (1956 postulated by Siebert, Peterson, and Schramm – regulation, ownership, censorship, and licensing. Before rounding off this chapter, Zelizer persuades us, if only briefly, to consider the role of language and rhetoric in politics and journalism (pp. 170-171). In conclusion, Zelizer says that existing ways of explaining how the political and journalistic worlds intersect may not have captured the entire picture of what journalism does, though it might have given us a fair idea of what it ought to be. Discussion Questions: 1) Are journalists political actors or mere intermediaries? 2) Is the political influence of journalists overstated? 3) Should journalists listen and relay or tell and influence? 4 Schudson, M. (2002). The news media as political institutions. Annual Review of Political Science, 5(1), 249-269. [Library Gateway] Schudson opens by asserting that political science has tended to neglect the study of news media as political institutions. He defines what he calls the three general approaches that have predominated sociological, communication, and political science scholarship on the news media: 1) Political economy perspectives focus on patterns of media ownership and the behaviour of news institutions in relatively liberal versus relatively repressive states. 2) A second set of approaches looks at the social organization of newswork and relates news content to the daily patterns of interaction of reporters and their sources. 3) A third style of research examines news as a form of culture that often unconsciously incorporates general belief systems, assumptions, and values into news writing. Though these come from three traditional approaches – political economy, sociological, and cultural, Schudson posits that all there recognize (or must) that news is a form of culture. He qualifies this proposition by emphasizing that this does not mean that news resides in a symbolic vacuum, but is invested with and in the political, economic, and social dimensions of society. (pp. 251). Schudson divides up the paper to discuss the following dimensions of the news media: The Political Economy of News 1) The link between ownership of news organizations and the character of news coverage, under which he discusses market-dominated and state-dominated news systems. 2) The implications of the growth of news conglomerates. 3) Control of news by powerful elites. 4) What role the media play in social change? The Social Organization of Newswork In this section, Schudson deals with the journalists, their sources, and the ‘beat system’ and what implications it has for the way journalism is produced. He argues that “the basic orientation of social scientists is that political news making is a reality-constructing activity that follows the lead of government officials.” (pp.255) 1) ‘Pack-journalism’, where in reporters of a certain beat function like a herd. 2) Reliance on government officials does not guarantee pro-government news. 3) ‘Resource-poor organizations’ have great difficulty in getting the media’s attention (Goldenberg, 1975). 4) There has been more attention paid to reporter-official relations than to reporter-editor relations. 5) Most research, then, has focused on the gathering of news rather than on its writing, rewriting, and “play” in the press. 6) Some American scholars have insisted that professional values are no bulwark against a bias in news that emerges from the social backgrounds and personal values of media personnel. Lichter et al. (1986) made the case that news in the 5 United States has a liberal bias because journalists at elite news organizations are themselves liberal. 7) Little said about differences between print and television news. Cultural Approaches Here, Schudson makes an analytical distinction between the understandings of news generation in the cultural and socio-organizational schema. These are the main talking points: 1) “The cultural view finds symbolic determinants of news in the relations between “facts” and symbols. That is, a cultural view might help us understand symbolic images employed to propagate stereotypes. 2) This prism also addresses journalists’ intuitions and descriptions of what is, or is not, news. 3) News judgement is not as unified as the system of ideology (functional here) suggests. 4) The cultural dimension of news concerns its form as well as its content. 5) Journalists operate not only to maintain and repair their social relations with sources and colleagues but also their cultural image as journalists in the eyes of a wider world. For instance, television news reporters deploy experts in stories not so much to provide viewers with information but to certify the journalist’s “effort, access, and superior knowledge” (Manoff 1989). 6) Journalistic objectivity is subjective. In conclusion, Schudson urges us to contemplate over the role of elites in news media communication, warns us against thinking about the media in ahistorical frameworks, and debate the nature of media power and influence. Cautioning us against leaning too much towards the debate over media effects, he says, in his words, “The primary, day-to-day contribution the news media make to the wider society is one that they make as cultural actors, that is, as producers—and messengers — of meanings, symbols, messages... It offers the language in which action is constituted rather than the cause that generates action.” Andrews, K. T., & Caren, N. (2010). Making the News. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 841. [PDF] This paper asks a specific question – what organizational, tactical, and issue characteristics enhance media attention? The authors situate this larger inquiry in a case study in which they combine detailed organizational survey data from a representative sample of 187 local environmental organizations in North Carolina with complete news coverage of those organizations in 11 major daily newspapers in the two years following the survey (2,095 articles). They seek to address the intersections of social movements, public agenda, and media reportage. Points of entry: 1) The news media can shape the public agenda and influence public opinion and elites by drawing attention to movements’ issues, claims, and supporters. (Agenda-setting and shaping) 2) Why are some movement organizations more successful than others at gaining media attention? 6 The article addresses the concept of media attention and the theories and evidence of newsmaking in its initial sections. An important question raised here is: “What drives media attention? As part of their discussion, the authors cite Galtung and Ruge (1965) and their 12point formula of newsworthiness, which has been addressed in the summary of the first reading for this class. Further, they emphasize the distinction between news values and news routines (pp. 844). Next, the authors discuss, in very brief, the theory informing protest and collective action in the news, and movement organizations and media attention. The authors hypothesize their study around two parameters: 1) Organizational Capacity (We… expect older organizations with greater staff, formal committees, networks, and members to gain a larger share of media attention). 2) Strategy and tactical repertoire (Organizations that use outsider tactics should receive less media attention. Confrontational strategies may generate colorful and dramatic copy but have minimal legitimacy). The greater part of the article is devoted to research design, data, analysis and methodology (pp. 847-856). Conclusions: 1) Overall, the findings… indicate that news media report more extensively on organizations that are geographically proximate, have greater organizational capacity, mobilize people through demonstrations or organizations, and use conventional tactics to target the state and media. 2) More resourceful organizations are better able to establish and maintain relationships with the news media and may also be better able to signal the legitimacy of the organization and its claims. 3) Demonstrations are an especially powerful strategy for gaining media attention, and this positive relationship is present even in models controlling for organizational resources and issues. 4) Organizations working on issues that address economic and social dimensions of the environment gain greater media attention. Discussion Question: 1) What do the findings of this study make us think about the co-dependency nature of social movements – within and between webs of traditional and innovative networks and their equation with mainstream and de-centered media? Robinson, S. (2011). Convergence Crises: News Work and News Space in the Digitally Transforming Newsroom. Journal of Communication 61, 1122-1141. [Library Gateway] Robinson’s inquiry, to me, as a journalist in India who started out in the profession without the assistance of Google or social networks, with bare access to the WWW, and someone could not afford a cell phone to communicate with my sources, hit all the right spots in terms of the questions she was asking. The broad question, as I understand it, that she seeks 7 answers and pointers to is how are systems of production in the digitally-driven, ‘convergent’ newsroom, impacting the production of information in contemporary news outlets? Her abstract clearly states the methodology employed: newsroom ethnography and in-depth interviews. She seeks to situate labor and power dialogues within the altered digital newsroom, addressing changed hierarchies and the privileging of those journalists conversant with contemporary technologies. She asks how the new norms might fit, or not, with structures of old rules in legacy media organizations and what implications the transforming workplace culture in newsrooms have for the quality of journalism (specifically in the US). In an age when publishers and editors have publically committed to incorporating interactivity, multimedia, social media, and other digital cultural artefacts to create ‘‘better,’’ more relevant news products, what is the nature of push-back from journalists trained in one medium (print) and how might this affect the way the public receives and consumes news? Robinson introduces us to the literature on spatial culture, and leads into a discussion on how journalists negotiate their work and newly altered work spaces, which turned traditional notions of hierarchy on its head while still keeping power systems intact. The tensions between older print journalists and newer ‘techie’ journalists (conversant with the dialects of the digital age – both technologically and culturally) are well documented in Robinson’s ethnographic notes. Much of the article is devoted to notes on what Robinson observed during her observantparticipant role at her location of study. It makes for interesting anecdotal reading, which is beyond the scope of this summary. But it is a must-read because it helps us question our media-user notions of news production. Robinson is clear to situate her analysis in the changing world of print journalism and makes no claims to extrapolate her observations to the news industry as a whole. But, her detailing of the changing place and process of print journalistic production could well serve as a template to investigate how spatial and labor changes are influencing the creation, dissemination, and consumption of news products across other evolving media platforms. Discussion Questions: 1) What is a journalist’s workplace today? 2) What does the digital age mean for newsroom culture and therefore quality of news? 3) Has the 24X7 news-cycle diminished the value of news? 8